Parley AIR: Plastics and Women's Health

Plastic pollution is a global health crisis we are only just starting to understand.

When World Health Day (April 7) was first recognized 73 years ago, synthetic polymers had yet to invade every known environment on Earth. This year’s theme focuses on building a fairer, healthier world, including gender disparities in health. When you look at plastics through this lens, the urgency of action is impossible to ignore and it points to some larger issues we have to address together. Below, we dive into the complicated interconnections between plastics, women’s health, everyone’s health, fertility, climate change and beyond. Plus, some everyday steps you can take and share to reduce exposure to hormone-disrupting chemicals.

Take the Parley AIR Pledge and receive our monthly AIR newsletter

The links between plastics and women’s health

At least 4,000 known chemicals are used to make plastic. Manufacturers mix, melt and press a cocktail of these substances to create everything from cooking utensils to skateboards. And because the chemicals are mixed, we often don’t know which ones are in which products. But what we do know is that some of these chemicals carry huge health consequences.

When European researchers looked at eight types of plastics, they found that three out of four contained toxic chemicals. They weren’t used in obscure products, either. These plastics were used in things like yogurt cups and sponges. They also detected 1,400 substances in total, but could only identify 260 of them.

Scientists don’t fully understand how most of these chemicals impact human health. A lot of the research that has been done has been conducted on animals, not humans. But among the chemicals the European researchers found were ones that are known to interfere with hormones. Hormones control heart rate, metabolism, growth and development, mood, how your body deals with stress, sleep cycles, sexual function, body temperature and reproduction. Others were linked to oxidative stress. This type of cellular damage speeds aging and is an underlying cause of cancer.

No one is immune to carrying these chemicals in their bloodstream, but women and people who are assigned female at birth (AFAB) tend to naturally have more body fat, which increases the amount of toxins the body stores. Others are more likely to use personal care products that contain chemicals disguised as “fragrance.”

It feels hard to avoid toxins when they seemingly lurk everywhere. But understanding which culprits are the worst is step one in reducing exposure.

Eating and drinking

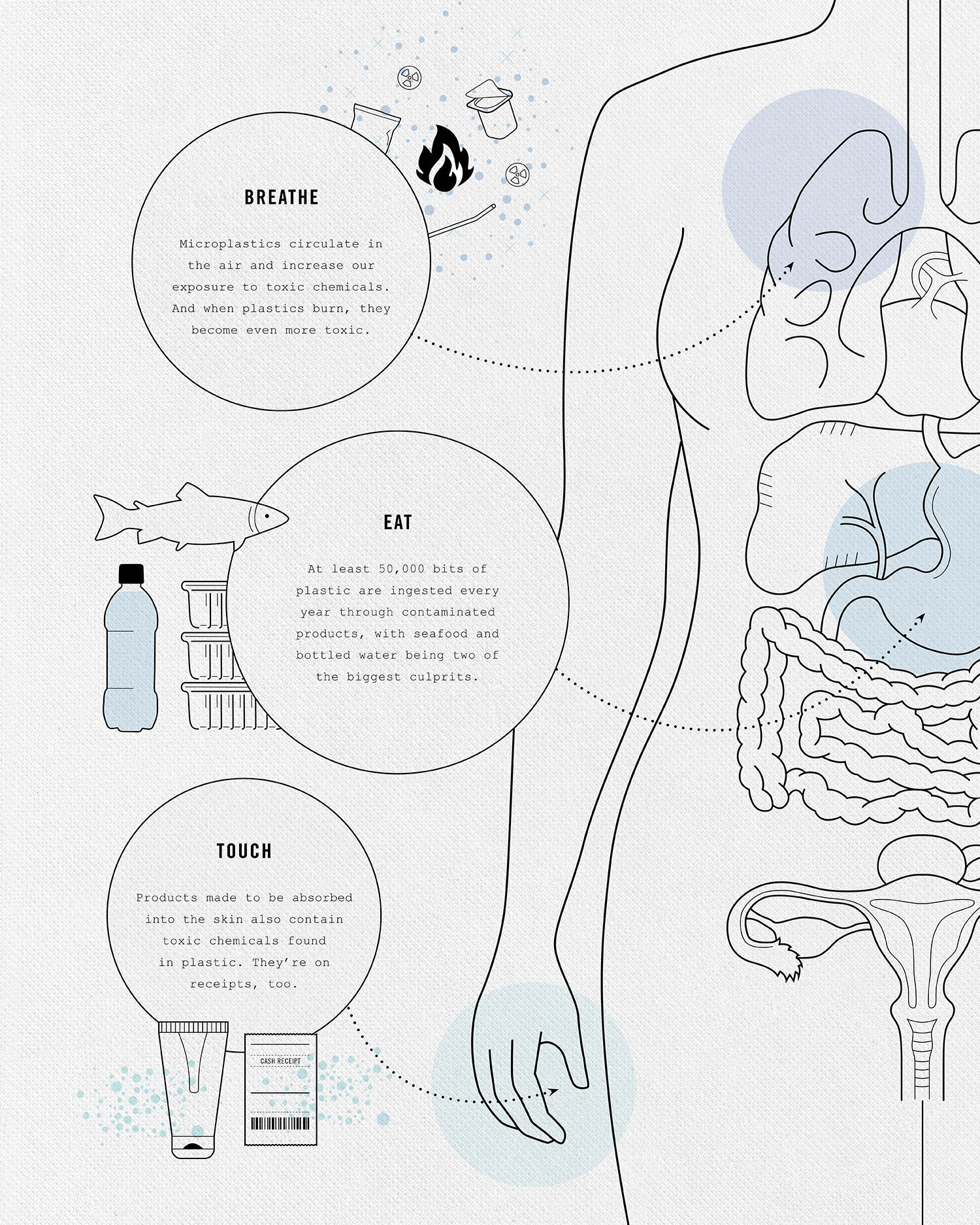

A recent study in Americans found that people eat, drink and inhale between 74,000 and 121,000 bits of microplastic every year. Seafood and bottled water are two of the biggest culprits.

Breathing

Sure, microplastics in the air increase exposure to toxic chemicals. But when plastics burn, they become even more toxic. The heat frees trapped chemicals and releases them into the air. People have already intentionally burned around 12 percent of all plastic. But wildfires are becoming both stronger and frequent around the world. Burning plastic from homes, cars and stores send chemicals into air and water, and into people as a result.

Touching

Skincare products, makeup and perfume are just a few of the products actually made to go on the skin that also contain toxic chemicals found in plastic. They’re on receipts, too.

Endocrine disruptors interfere with hormones

There are thousands of chemicals used in plastic products but scientists still don’t know much about how each one impacts human health. Two chemicals — bisphenol A (BPA) and a class of plastic-making chemicals called phthalates — have been thoroughly studied. Researchers have found that both are endocrine disruptors. Simply put, endocrine disruptors interfere with hormone production, and they have been linked to cancer, reproductive problems and issues with the immune and nervous systems.

Bisphenol A (BPA)

If you’ve only heard of one chemical commonly found in plastic, chances are it’s BPA. In the 1950s, scientists discovered that BPA works great in a clear, hard plastic called polycarbonate. You’re definitely familiar with the material: It’s used in everything from sunglasses to bike helmets to medical devices like incubators.

Since about 2003, governments around the world have been commissioning studies on BPA safety. In the beginning, most concluded that the amount of BPA people are exposed to in everyday products didn’t pose any health risk. But by the 2010s, these same governments started banning BPA from being used in baby bottles, formula packaging and sippy cups after studies showed the chemical interferes with hormones that impact the reproductive system.

Since then, research has shown mixed results about what BPA does to the human body and the chemical isn’t being researched as frequently as it was 10 years ago. The good news is, federal governments including the European Union are asking scientists to take another look at the potential health effects of BPA. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency says it’s concerned about the chemical because animal studies have determined it to be a reproductive toxicant, among other things. The evidence is mounting.

So far, research has found that even in small amounts, BPA is an endocrine disruptor, most likely because it’s structurally similar to estrogen.

In 2015, scientists in China reviewed six studies on how BPA impacts female fertility. They found that the body of research showed that BPA interferes with glans linked to puberty and can cause structural changes to the uterus and ovaries, which particularly impacted by BPA. This damage has been linked to infertility, ovarian cysts and ovarian cancer. One early study on women undergoing fertility treatment found that those who had higher amounts of BPA in their system had fewer eggs that had matured to the point where they could be fertilized.

It’s important to point out that fertility is never just a female issue. And mounting research shows that everyday chemicals like those found in plastic are fueling a rise in infertility in all genders.

Phthalates

Phthalates are another hormone-disrupting chemical that’s found not only in plastic packaging, but lotions, shampoos, nail polish and makeup. It’s nicknamed the Everywhere Chemical because it’s so widely used. To give you an idea, here's a list of all the products in which the U.S. FDA found phthalates in 2010.

Even seemingly safe organic foods can be encased in phthalate packaging. A recent study also found high amounts of phthalates in menstrual pads purchased in Korea, Japan, Finland, France, Greece and the U.S. There are eight main types of phthalates and on American products, the chemicals can simply be listed as “fragrance.”

Researchers have determined that phthalates are present in almost everyone, but especially women of childbearing age. One study in more than 250 American women linked a phthalate called di-2-ethylhexyl, which makes plastic flexible, to miscarriages. Another study of 350 pregnant American women found that those who had higher traces of monoethyl phthalate (MEP), which is used in cosmetics and perfumes, were more likely to excessively gain weight during pregnancy. The study authors stressed that this put the women at a higher risk of developing gestational diabetes.

Regulations that curb phthalate in everyday products aren’t as widespread as they are for BPA. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency recognizes DEHP, which is among the most widely-used phthalates, as a probable carcinogen, though its use is still permitted in the country. Other countries have banned the chemical in certain products. For example, Canada has banned the use of DEHP in cosmetics and restricted its use in other products including toys.

In the past couple of months, advocacy groups have amplified their requests for governments to ban certain phthalates and public health experts have joined in. Eight experts published a statement this month in the American Journal of Public Health, highlighting the fact that animal studies –– which aren’t as scientifically sound as human studies –– have linked phthalates with delayed brain development and issues with both male and female reproductive organs. The health experts argue that the effects seen in animals are reason enough to curb human exposure to phthalates, especially in BIPOC communities who are frequently exposed to higher amounts of dangerous chemicals.

Scientists have found microplastics in human placentas

Italian researchers published a study in late December that found microplastics in human placentas for the first time. The 12 tiny shards of plastic had made their way into all parts of the placentas of four mothers, including in the two membranes that make up the amniotic sack that surrounds the baby. In total, they looked at placentas from six different women, meaning more than 65 percent of the small sample contained microplastics. The team also only tested about 4% of each placenta for plastic.

The researchers believe the mothers unknowingly ate or breathed in small pieces of plastic that were carried to the placenta through their bloodstream.

It was clear the plastic had likely come from everyday products. Three of the pieces were polypropylene, a soft type of plastic that’s used to make everything from yogurt containers to prescription bottles. The researchers used pigment in the remaining nine to trace them back to pigments used in man-made coatings, paints, adhesives, plasters, finger paints, cosmetics and dyes typically used to color cotton and polyester.

Scientists don’t yet understand how the chemicals in plastic impact a developing fetus but the ones who performed this study worry that it could interfere with the immune system. An altered immune system could make the babies less equipped to fight off pathogens and alter how they can use energy stores.

BPA is in breast milk

Scientists have been finding BPA in breast milk since the early aughts, but it’s still unclear what this means for babies. In one small study of mostly white women, researchers tested breast milk for BPA and found the chemical in 75 percent of samples. None of the mothers recalled being exposed to the chemical. The same researchers tested babies, some who were formula-fed and some who were breastfed, and found BPA in 93 percent of the babies’ urine.

In another study published last year, researchers wanted to better understand what BPA exposure means for babies. The study included almost 200 women in China and found that of the three plastic-linked chemicals researchers detected in breast milk, BPA was most prevalent. To better understand how this may be affecting babies, they compared the amount of BPA in each mother’s milk with her baby’s weight. Babies that were exposed to more BPA were smaller.

More research needs to be done to confirm whether or not this was a coincidence, but the researchers believe that the BPA carried from mother to baby through breast milk could affect the baby’s growth.

Because BPA and similar chemicals are so prevalent in the things we consume every day, and especially in food packaging, it’s virtually impossible for mothers to avoid passively ingesting at least some. The good news is that dozens of countries including the United States, Canada, the European Union, China and Malaysia have banned the sale of baby bottles made with BPA. However, a recent study found that baby bottles made of a soft plastic called polypropylene, which is BPA-free, shed millions of microplastic bits into the liquid they contain, where there’s nowhere to go but down the hatch.

Women are disproportionately impacted by plastic, pollution and climate change. They’re also spearheading solutions.

The plastic and the fossil fuel industries are deeply intertwined. More than 99 percent of plastics are made from fossil-fuel-sourced chemicals. If the trend continues, plastic production will account for 20 percent of all fossil fuel use in less than 30 years. Natural gas wells clear carbon-trapping forests, so the climate impact of refined oil and gas begins long before the raw materials are extracted. When you consider the footprint of transporting plastic raw materials, products and waste, along with reports that plastic releases greenhouse gases, the heat-trapping potential of plastic is greater and more enduring than we know.

A study published last year included 80 case studies that linked climate change and environmental pollution and destruction to violence against women. This is especially true in countries with high rates of poverty.

Informal waste management both creates jobs for women and exasperates gender inequality in the plastic industry. Women are more likely to work as informal waste collectors than in formal waste management and reports show that in informal waste management economies, highly recyclable, and therefore more valuable plastics, are typically reserved for men in countries throughout Africa, Latin America and Asia. If women do sell these types of plastics, they’re often paid less for them than a man would get. In the end, they are paid less for working in the same toxic environment.

Women are disproportionately impacted by plastic, pollution and climate change, but they’re also heading up solutions.

Studies have shown that women drive household purchasing power, meaning they more often get to choose what products enter the home. Female scientists, activists, writers and business leaders have taken iconic strides that have shifted the way society understands conservation, climate change and the impact we have on our planet. Climate leaders are calling for a feminist climate renaissance, not only to amplify marginalized voices but to harness the power women have to drive change.

Turning toxins into motivation —

When Parley collaborator Emily Penn tested her blood for 35 toxic chemicals used in plastic, she found 29. Some were carcinogens, others were endocrine-disruptors. All of them scared her, so she formed an all-female crew and set sail on an expedition dedicated to studying the plastic trash in our oceans. [Read more]

Women are leading the charge —

Across the Parley crew, our network and this movement, women are paving the way for change. Meet some of the Parley team leaders here: Judith Adriana Morales López, director of Parley Mexico; Shaahina Ali, director of Parley Maldives; Tavake Pakomio, director of Parley Rapa Nui; Alvania Lawen, director of Parley Seychelles; Juliana Poncioni Mota, director of Parley Brazil… we’ll continue to profile change-makers on @parley.tv.

What you can do about it

We get that our world isn’t set up in a way that you can completely avoid all plastics all the time. By now, we all know that we should rethink single-use plastic bottles. We know to bring reusable bags to the grocery store. But avoiding plastic food packaging can be a bit more complicated. Still, there are plenty of ways you can significantly reduce how much you come into contact with plastic (and encourage a plastic-free future in the meantime).

Most cans in the U.S. are now BPA free, but not all. Look for BPA free on the label and double check that bisphenol S (BPS) and bisphenol F (BPF) haven’t been used as a replacement. These replacements may be even more harmful than BPA. Better yet, buy dried beans in bulk using your own reusable (not plastic) container. Make your own soups and chili, and freeze fresh vegetables in reusable glass containers instead of buying canned or frozen.

Cut back on takeout. People eat at least 50,000 plastic particles every year. Most of this comes from single use plastics that a lot of people can easily avoid.

If you have to buy plastic, avoid any packaging with the number 7 stamped inside the recycling sign. These commonly contain BPA. Another one to avoid is number 3, which is usually found on flexible plastic that contains phthalates. Also, milk and spices are most susceptible to absorbing phthalates from food containers, so this goes double for them. Again, avoid plastic if at all possible. But if you can’t, those marked with a 1,2,4 and 5 recycling code are considered the least toxic, chemical-wise.

BPA has been banned from baby bottles and sippy cups since 2012, but harmful chemicals still appear in children’s products such as plastic dinnerware, food packaging, storage containers, and plastic bags. Look for glass, bamboo and food-grade stainless steel alternatives whenever possible. At playtime, avoid plastic toys.

Store leftovers in metal or glass food containers. If plastic is your only option, definitely don’t store fatty foods in these containers. Many of the chemicals in plastic are fat-soluble, meaning they will more easily leach into foods that contain a lot of fat. Also, replace plastic wrap with a reusable option like beeswax wrap. And never, ever microwave plastic containers.

Reduce or eliminate seafood from your diet. Fishing nets are a major source of marine plastic pollution, and overfishing is currently decimating life in the oceans. Furthermore, chemicals bioaccumulate as they move up the marine food web. The larger the fish, the greater the risk of contamination.

Use plastic-free pads or tampons, or a reusable option like a menstrual cup. A recent study found high amounts of phthalates in menstrual pads purchased in Korea, Japan, Finland, France, Greece and the U.S

Skip the receipt. Studies have found that thermal paper receipts from retailers and restaurants can contain a mass of BPA that is 250 to 1,000 times greater than the amount in a can of food.

Stick with personal care products (shampoo, makeup, skincare) that are transparent about ingredients. Bonus points if they come in plastic-free packaging.

Buy deodorant that comes in cardboard or other non-plastic packaging. Or make your own. Toothpaste is another staple you can actually DIY.

We spend hours scrolling through our phones every day, so the next time you need a new phone case, choose a case that’s not made of plastic. Shoot for a biodegradable case made from non-toxic plants. Wood or bamboo can also be good options, just make sure there isn’t a plastic finish on it that might defeat the purpose.

Talk about it. Take steps — no matter how small they may seem — to reduce the amount of plastic you use and encourage your friends and family to do the same.

TAKE ACTION

There’s strength in numbers but it starts with one. Read up, make noise, spread the word and give others the tools to do the same. This is the best way to drive world leaders to adopt policies that will slow climate change and help the oceans stay healthy so they can play their role.

IG @parley.tv | FB @parleyforoceans

#ParleyAIR