PARLEY AIR: Plastics and Climate Change

Plastic is created from fossil fuels, and it may be the industry’s only chance of keeping afloat

Almost every piece of plastic starts as fossil fuel, and scientists recently discovered that planet-warming gasses are released at every stage of the plastic life cycle. A global surplus of oil and demand for renewable energy is now driving fossil fuel companies to seek out new sources of demand. Some see plastic as their best bet.

Take the Parley AIR Pledge and receive our monthly AIR newsletter

Plastics are made from fossil fuels

Plastics, oil and natural gas are deeply connected.

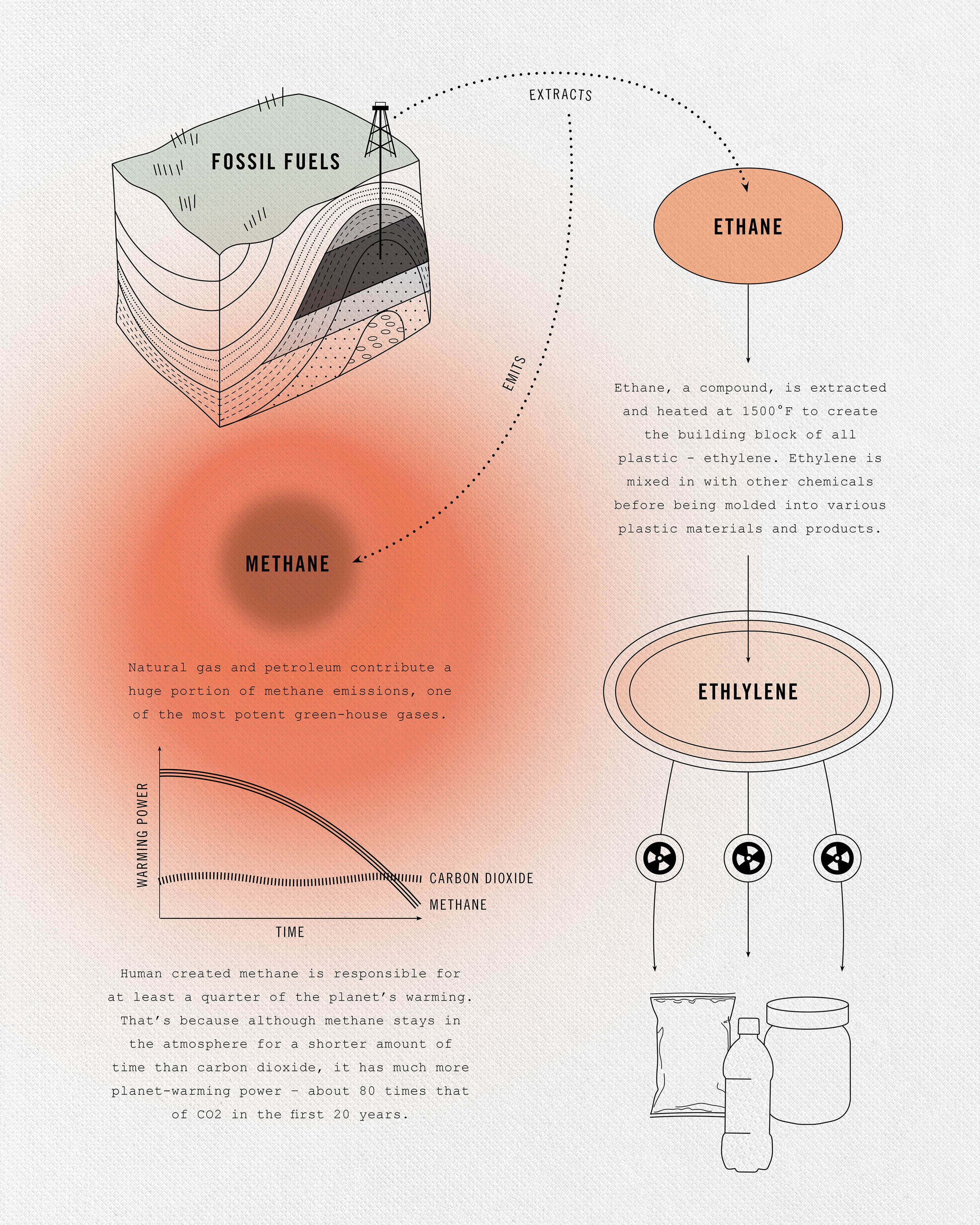

Ninety-nine percent of plastic is made from a compound called ethane, which comes from oil and natural gas. Basically, ethane is heated to around 1,500 degrees Fahrenheit, which forces its molecules to break apart. This leaves the building block of all plastic, ethylene, which manufacturers mix with other chemicals before molding the polyethylene resin into buckets, makeup containers and baby bottles.

This entire process is energy-intensive and polluting on its own, but it’s also driving demand for oil and natural gas production.

According to estimates from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, natural gas and petroleum are responsible for almost one-third of total U.S. methane emissions, one of the most potent greenhouse gases. Human-created methane is responsible for at least one-quarter of the planet’s warming. That’s because although methane stays in the atmosphere for a shorter amount of time than carbon dioxide, it has much more planet-warming power — about 80 times that of CO2 in the first 20 years.

There are conflicting estimates regarding just how much methane is in the atmosphere today and how much is being added every year. But we do know one thing for sure: agriculture and fossil fuel production are the largest human-created source of methane. And that excess methane in the atmosphere is heating the planet.

About 6 percent of the world’s oil and gas currently goes to creating plastic. But fossil fuel companies are hedging bets that plastic will soon prop up the industry.

The International Energy Agency expects plastic and other petrochemical products — like fertilizer, synthetic rubber and antifreeze — to drive one-third of the world’s oil and gas demand in the next decade, and a full half by 2050. This demand would completely offset any progress made by falling demand for gas used in transportation.

According to a 2020 report by the Carbon Tracker Initiative, BP expects the plastic industry to account for 95 percent of its net growth in demand for oil between 2020 and 2040. And it’s not alone. As a growing demand for renewable energy decreases demand for oil and gas, executives see fanning plastic production as the most viable way to keep fossil fuel companies afloat.

As it stands right now, just 20 corporations — including oil and gas, chemical companies — produce 55 percent of the world’s single-use plastics. One hundred are responsible for 90 percent. And in May 2021, the Plastic Waste Makers Index reported that oil and gas giant Exxon Mobil is already the largest single-use plastic polluter in the world.

Fracking is fueling new plastic projects

Most of the natural gas extracted in the U.S. doesn’t come in free-flowing reservoirs. Instead, gas companies have to force it out of rock beds — usually shale — using water, sand and chemicals. This is hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, a highly polluting process that’s created a global surplus of oil and gas.

This surplus has tamped down oil and gas prices since 2016, which sent fossil fuel companies looking for ways to create demand for their reserves. According to the American Chemistry Council, fracking has created 349 new petrochemical projects in the U.S. since 2010, mostly in Texas, Louisiana and Pennsylvania. American ethane exports have also swelled from almost zero in 2013 to an average of 260,000 barrels per day in 2018. Canada — via pipeline — is the main importer, followed by India and then the U.K. But Europe isn’t far behind.

In 2016, a British-based chemicals company launched a custom-built fleet of ships that began carting U.S.-fracked ethane gas to processing facilities in Britain, Norway and Sweden. The company now has plans to build a cracking facility in Antwerp, Belgium. It would be the first new ethane cracking plant in Europe since the 1990s.

The new project would double Europe’s consumption of imported ethane — with the single plant consuming half of all U.S. ethene imported to European for ethylene production.

Antwerp is no stranger to plastic manufacturing, but the plant would make the city the second largest hub for petrochemicals in the world, after Houston, Texas, and would provide a steady stream of ethylene for the existing plastic manufacturers in the area. The project isn’t set in stone yet, and the European Union is officially banning single-use plastic cutlery, cotton pads, straws and stirrers this year, giving those against the fracking-fed ethene plant hope that the project won’t be built.

The Plastic Waste Route

It is absolutely better to recycle plastic than to toss it in the trash — recycling a plastic bottle consumes 76 percent less energy than making it from scratch — but recycling can spark a false sense that single-use plastic is harmless as long as it’s turned into something else. The truth is, even recycling has a huge carbon footprint.

Most plastic isn’t recycled in the first place — only about 9 percent of what’s created. But when it is, plastic can travel as much as 8,000 miles before it reaches a recycling facility. That’s because just a handful of countries are responsible for processing the lion’s share of global plastic waste, and shifting policies are constantly changing to which countries plastic waste is being routed.

One thing does stay constant, though. High and upper-middle-income countries account for almost all plastic waste exports, and lower-income countries bear the brunt of the plastic waste burden.

Estimates vary as to which countries are the biggest contributors to the plastic waste stream, but the United Nations reported in 2020 that the biggest plastic waste exporters are the European Union (40 percent) — especially Germany — the U.S. (15 percent), and Japan (12 percent). For three decades, most of this plastic was shipped to China. But in 2017, China banned most plastic imports.

This was a huge deal because at the time, China had been importing almost half of all global plastic waste exports.

The following year, Indonesia, Malaysia, Korea, Thailand, Vietnam and Taiwan introduced restrictions of their own. The countries had absorbed a huge amount of global plastic waste exports after China’s restrictions. The loads flooded the countries with plastic waste, including toxic chemicals.

According to the United Nations, global exports of plastic waste nearly halved in the year following the mass restrictions. But if you just count the amount of plastic waste shipped overseas from the U.S., the carbon emissions of that half was still equivalent to the annual emissions of 26,000 cars.

Plastics release methane as they break down

Plastic doesn’t just create greenhouse gas emissions when it’s produced. In 2018, researchers at the University of Hawaii discovered that plastic also releases methane as it breaks down and is exposed to sunlight. The more surface area it has, the more stored methane it can release. Get the full story here.

Plastic pollution in the ocean blocks the world’s largest carbon sink

The world’s oceans consistently absorb about 30 percent of atmospheric CO2, so as the amount of CO2 in the air increases, so does the amount stored in the seas. (As a side note, that extra carbon burden is acidifying seawater, which makes it harder for coral reefs and shellfish to build their skeletons.) Researchers are beginning to understand that plastic pollution in the ocean inhibits the blue giants’ ability to absorb greenhouse gases from the atmosphere — which is a huge problem that has the ability to significantly accelerate climate change. That’s because through many avenues, plastic pollution interferes with vital biological processes in marine ecosystems.

This starts at the very bottom of the food chain. Although the research is still young, scientists believe that phytoplankton (microscopic plant life) and zooplankton (microscopic animal life) are impacted by microplastic pollution. This could have huge consequences for climate change because phytoplankton and zooplankton make up the basis of marine ecosystems and are the ones tasked with carbon sequestration — phytoplankton alone capture as much CO2 as four Amazon Rainforests.

These tiny flora and fauna grab CO2 from the ocean’s surface and store it so the greenhouse gas can’t reenter the atmosphere. Phytoplankton do this through photosynthesis, but early lab research has suggested that microplastic can interfere with the process. Microplastic may also impede metabolic rates, reproductive success and survival of zooplankton that eat them.

At the same time, larger marine animals are increasingly dying from accidentally eating plastic pollution. UNESCO estimates 100,000 marine mammals die from plastic pollution every year.

The climate impact of the increasing trend is seen most clearly in whale populations. A great whale — which includes gray, humpback, right, blue, sperm, bow- head, fin, sei, Minke, pygmy right and Bryde's whales — captures around 33 tons of CO2 during their lifetime and stores it in the sea for centuries.

Whale poop is also vital for plankton production, the most powerful carbon-storers in the ocean. And because the mammals are near the top of the food chain, they act as huge carbon sinks for the CO2 that other ocean life absorbs. This continues after they die. The overwhelming majority of large marine animal carcases sink to the bottom of the ocean, where the carbon they absorb throughout their lifetime is trapped in the depths of the sea rather than released back into the atmosphere. One team of researchers valued every whale’s carbon-absorbing value at US$2 million.

Not only does plastic production contribute to atmospheric greenhouse gasses, it’s becoming clear that the finished product has additional climate consequences we’re just beginning to recognize.

Reading list

Understanding what’s going on is the first step in demanding change. So, we put together a list of resources that do a great job investigating the future of plastics, climate change and the fossil fuel industry — including one that outlines why fossil fuel companies may not be successful in driving global demand for plastic.

TAKE ACTION

There’s strength in numbers but it starts with one. Read up, make noise, spread the word and give others the tools to do the same. This is the best way to drive world leaders to adopt policies that will slow climate change and help the oceans stay healthy so they can play their role.

IG @parley.tv | FB @parleyforoceans

#ParleyAIR