For the Penguins

“It is practically impossible to look at a penguin and feel angry.”

Joe Moore

What’s not to love about a waddling flightless bird in a permanent tuxedo? Penguins (of the biological family Spheniscidae) are a gift to this fragile planet, albeit an often misunderstood and increasingly threatened one. Anyone who has seen March of the Penguins already knows the life of a penguin is no walk in the park.

The biggest threat to penguins is climate change. In some areas of the world, their populations have decreased by 80 percent as temperatures soar. In a heartbreaking new report, researchers say the world’s second-largest colony of Emperor penguins has collapsed due to drastic changes in their breeding environment. Meanwhile, their world (and bellies) fill with plastic.

Penguins are so beloved, the world has dedicated at least two holidays to their existence: Penguin Awareness Day on January 20th and World Penguin Day on April 25th. To honor the latter—in hopes of sparking action—we’ve rounded up some things you should know about our feathered friends in the Southern Hemisphere. Feel free to share. For the penguins.

Photo by Angie McCall

Photo by Agnes Brenière

There are 17 species of penguins. All of them are found in the Southern Hemisphere, save for Galápagos penguins hanging out at the Equator.

Penguins roll deep with their posses. All but two species of penguins breed in large colonies of up to a thousand birds.

Penguins range in size, build and adaptive advantages depending on the species. The tallest, the Emperor Penguin, measures at a towering 4 feet. The smallest, the Little Blue Penguin, is an adorable 16 inches. And the fastest, the Gentoo Penguin, can reach swimming speeds up to 22 mph.

Fossils suggest penguins date back some 60 million years, with an ancestral lineage stretching beyond the K-T boundary. A giant, waddling relative of the birds we see today could have survived the mass extinction of the dinosaurs. One might say that kind of resilience calls for formalwear.

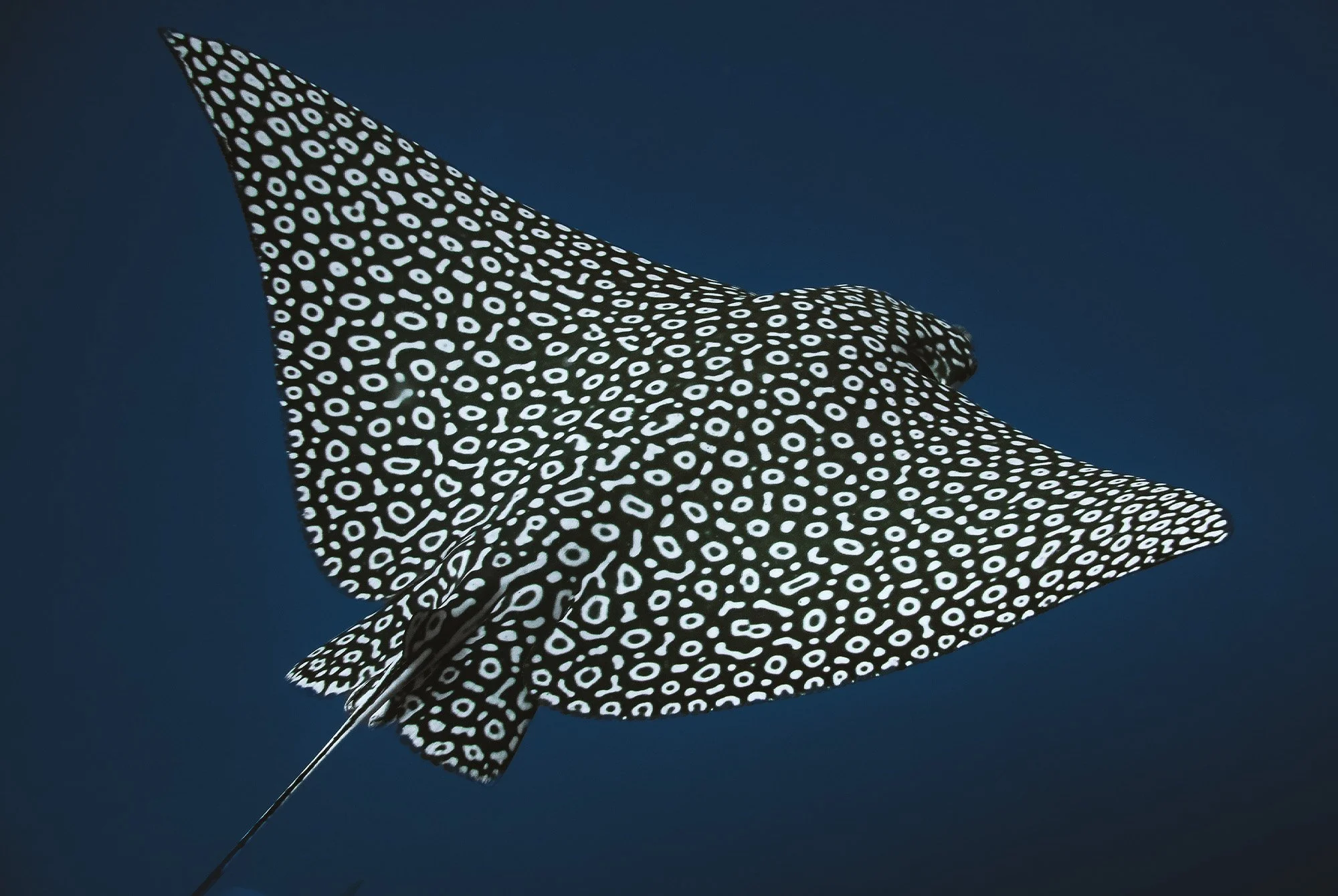

A penguin's contrasting coloring is more than a dashing getup, it’s also camouflage. From above, a black back blends into inky waters. To predators below, a white belly becomes one with the bright rays penetrating the water’s surface.

Penguins may look cute and cuddly but don’t be deceived. They are mighty hunters, with superpower-like underwater vision and the ability to dart through the water in pursuit of prey.

When hunting for fish, penguins ingest a lot of seawater. Fortunately, they evolved a special gland, the supraorbital, behind their eyes which filters saltwater from the bloodstream. Penguins then expel this salty liquid from their beaks by shaking their heads in what looks like little sneezes. Pretty cute.

Penguin feathers are tiny and tightly arranged in an insulating layer that traps heat close to their bodies. Adélie Penguins have about 100 feathers per square inch, a density far higher than that of other birds.

Though penguins stick to a certain ‘look’ throughout the seasons, sometimes they have to freshen up and replace the old with the new. Almost all penguins undergo a full molt once a year (the exception is the Galápagos penguin, which undergoes two). Called ‘catastrophic’ molting, the process involves shedding and replacing all feathers in the span of a few weeks.

Monogamy is a big thing in penguin society. It depends on the species, but many penguins will mate with the same member of the opposite sex (and sometimes the same sex) season after season.

Photos by Samuel Blanc

Like sea turtles and salmon, most penguin species return to the exact nesting site, or rookery, in which they were born to breed. Shockingly, that epic journey across frozen tundra is the simple part. Raising the next generation is not easy.

In some species, the male penguin incubates the eggs while the females leave to hunt for weeks at a time. This is good news for heftier males. Females look for a mate with enough extra fat storage to survive those long, cold, solo stretches while they hunt for sustenance.

Parenting is a collaborative effort in the colonies. Both male and female parents care for their young for several months until the chicks are strong enough to hunt for food on their own.

Penguins have excellent hearing, despite their lack of visible ears. They rely on distinct calls—like little love songs—to find their mate upon returning to vastly crowded breeding grounds. It’s not easy to spot your buddy when everyone’s dressed the same.

They also have special dance moves. Male Adélie penguins, for example, make funky movements with their head and flippers. Before you call them clumsy, watch one of these dances in slow motion, or consider how gracefully they move through the water. Perspective is everything.

Penguins face a long list of challenges beyond their control: global warming, overfishing, natural and invasive predators, illegal hunting and egg harvesting, industrial development and its accompanying habitat destruction, oil spills, pesticides and plastic pollution. Fortunately, many of these issues are within our control. Take steps to curb your carbon and plastic footprint, raise awareness, challenge oil drilling, rally for more marine protected areas, rethink those Omega-3 krill supplements, support organic farming methods and definitely never eat penguin eggs. There are many ways to use your voice and take action.

And while you work to make a difference, take comfort in a reminder from the fossil record: penguins are resilient. They’ve survived millennia of glacial changes and sea ice fluctuations. Their ancestors may have even outlived the dinosaurs. In the rapidly changing world of the 21st century, another silver lining could be harbored in climate refugia, safe havens where scientists believe penguin populations may survive periods of time on an otherwise inhospitable planet. Of course, we refuse to let things reach that point. The time to act is now. Creativity and collaboration are key.

The Penguin and the Plastic - A film by Henry West

Penguins are losing their habitats and swallowing our trash. More than 90 percent of the world’s seabirds have accidentally eaten plastic. By 2050, all species of seabirds will have plastic in their stomachs. Moved by this fact, filmmaker Henry West plunged into the mind of a young penguin on a trip to Antarctica.

“I set off on the adventure of a lifetime to my final continent of the world to explore, not knowing what to expect or what I would end up documenting. The inspiration for this short film came about when I was sieving through my footage, the penguins started talking to me in my head. I will never forget the time when a little Gentoo Penguin decided to run in between myself and camera, filling my heart with joy and capturing the moment forever. After this gift, it was ingrained that I had to create a story for all ages to understand that together we need to tackle the problem of marine plastic pollution and save the penguins”

Henry West, @mrhenrywest