In Focus: Lena C. Emery

We speak with the German-born, London-based photographer about her nomadic upbringing and a recent journey to document sperm whales in Dominica.

Lena C. Emery’s photographic practice is rooted in a life shaped by continual movement, having already lived in five countries across two continents by the time she was twenty. This early transience instilled a heightened sensitivity to the quiet details of place and presence, and to the invisible patterns that shape how we live. Her work lingers in the tension between distance and belonging, tracing the fragile threads that bind humans to the environments they so often forget they’re part of.

Trained initially as a painter in Paris, Emery turned to photography after relocating to London in 2012.Over the past decade, her practice has evolved to move fluidly between fashion, art, and documentary, with work exhibited at galleries such as FRIEZE No.9 Cork St, alongside commissions for brands like Dior, Hermes and Lemaire. Her contemplative gaze creates a form of quiet resistance, peeling back the layers of conditioning, not to capture or define, but to gently unlearn, asking us to look again, and this time more closely.

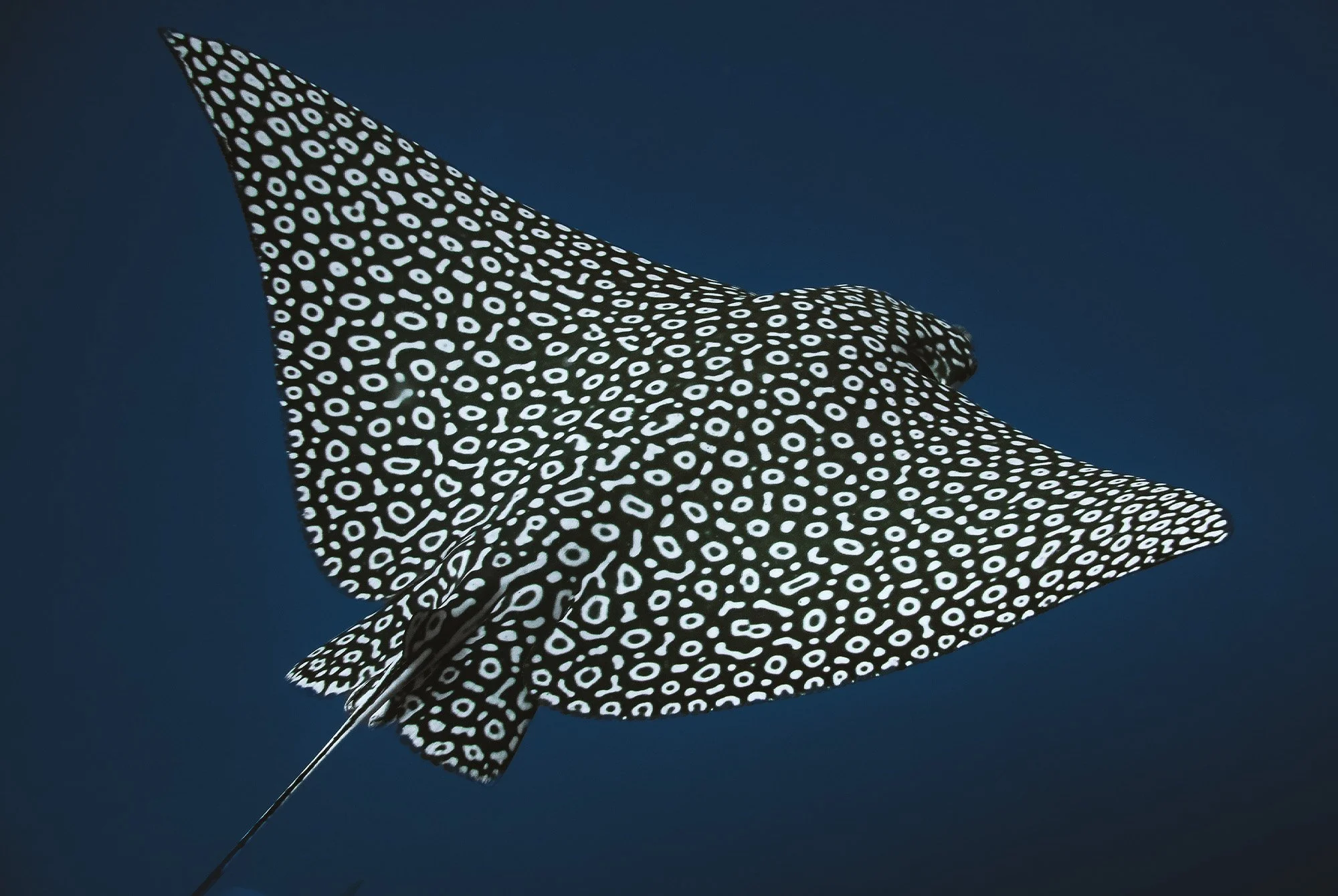

Her latest series, published in the new issue of Atmos, offers a tender and immersive portrait of a resident sperm whale family off the coast of Dominica. The project marks a deepening of Emery’s ongoing commitment to environmental storytelling, seeking to restore our connection with the more-than-human world.

In 2023, Dominica established the world’s first sperm whale sanctuary, safeguarding these at-risk animals across 800km of ocean, implementing measures to protect them from ship strikes, noise pollution and entanglement. The largest of the toothed whales, their numbers plummeted after nearly two hundred years of commercial whaling but the population is recovering, while still being faced with the dangers that human behaviour causes to all marine life. Like all whales, they play a vital role in regulating ocean ecosystems. Even in death their bodies offer life to the ocean floor, providing essential sustenance to all animals that exist in the deepest places on Earth.

“It felt like stepping into a world that moves at a different rhythm, older and wiser”

Lena C. Emery

Emery’s photos are mesmerising, images that take the viewer inside the majestic creatures’ vast blue home, shards of golden sunlight piercing the water’s surface and cascading over these benign giants. Emery photographs tender moments such as a mother with two calves, or whales sleeping vertically, totally motionless. She also released a film ‘Their Ocean’ that you can see below, launched in collaboration with Atmos and Parley, a three minute vignette soundtracked beautifully by Chiara Dubey. To celebrate the launch of the project, we caught up with Emery to discuss her childhood, her pathway into photography, and diving with the sperm whales of Dominica.

Q & A

I'd like to start by talking about the build-up to your stunning photographs of sperm whales. How do you prepare for a shoot like that, both mentally and logistically?

Before travelling to Dominica, I spent a lot of time reading and watching, especially about how sperm whales live and sense the world around them. I wanted to understand how to approach them with as little disturbance as possible. A book that really stayed with me during that time was An Immense World by Ed Yong. It explores how animals experience reality in ways that extend far beyond human perception. The way sea turtles navigate via magnetic fields, horses sense seismic vibrations or elephants communicate across vast distances using infrasound frequencies too low for the human ear to detect. We only experience such a narrow slice of reality. I think by becoming more aware of the unique sensory world of other animals, it allows us to behave and create in a much more connected way.

Logistically, we were fortunate to work with expert guides operating under permits from the Dominican government, which are carefully regulated to protect the whales and their habitat. Being off-grid and without equipment support meant planning for a wide range of possibilities and carrying more than we hoped we’d need. Still, the most unpredictable part often comes before the work even begins. After reaching St. Lucia, where we were meant to board a small propeller plane to Dominica, the crew weighed our gear and wouldn’t let us on. In the end, simply getting everything to the island with everything intact became its own quiet triumph.

What does it feel like to be in the water with them?

It’s hard to describe without leaning into the poetic, because the experience really does seem to exist on a different register. It felt like stepping into a world that moves at a different rhythm, older and wiser. The first time was so powerful it was almost disorienting. You can sense their empathy and intelligence and just feel incredible awe, that, and your own extreme insignificance. On the very last day when we had the most magical encounter with a larger pod, I think all four of us surfaced in tears.

How did this specific collaboration and working relationship with Atmos come about?

The relationship with Atmos began a few years ago through a story written by Nicola Jones at how different cultures shape and perceive colour in nature. Since then we’ve continued to work together across several issues. I have endless respect for Jake and Willow, the founders, and the way they’ve brought climate and culture into conversation with such originality and care. That thoughtfulness runs through the entire team. It’s rare to find a group of people who not only lead with intention but do so with such talent and kindness. Each collaboration has felt like a deeply meaningful exchange, and I’m truly grateful to be part of their vision.

I'd like to go back further. Could you tell me how you became a photographer and what your entry point into the artform was?

We moved often when I was growing up, twelve times across five countries and two continents by the time I was twenty. That constant shifting created a sense of both urgency and dislocation. I was always adapting, always trying to make sense of unfamiliar surroundings. I think that’s where the instinct to observe and record began. Photography came later, but the impulse to hold onto something fleeting, to anchor myself through looking, was there early on.

This repeated relocation became a kind of ongoing process: re-evaluating the past, adjusting to the present, imagining different futures. Photography eventually gave shape to that process. It became a way for me to work through questions of identity and place, a tool to navigate uncertainty and make sense of the landscapes I moved through, both physical and internal.

While still in high school I came across the work of Austrian naturalist Joy Adamson, who moved to Kenya in the 1930s and spent decades living alongside and caring for wild animals. Her trilogy Born Free, Living Free, and Forever Free, about raising and releasing a lioness named Elsa, was pivotal for me. She lived with a deep sense of purpose, blending creativity, personal story, and advocacy while forming relationships with wild beings. That way of living, immersed in the natural world and engaged through multiple forms of expression, is something I’ve been trying to emulate ever since.

After school I left Singapore to live on Wakatobi, a remote marine reserve and dive resort that my father had helped establish. From there I moved to Bali, and later applied to art school in Paris, where I studied painting while living on a houseboat in Asnières-sur-Seine. It wasn’t until I eventually arrived in Berlin that I began to focus on photography in a more sustained way.

Coming to London happened almost by chance. I didn’t know anyone and had just enough savings to last a few months, so I leaned into whatever opportunities came my way and built something from that urgency. Fashion became a space to explore visual language within a system I was both navigating and questioning. It was messy, nonlinear, and often improvised, but through it I kept circling back to the same concerns: how we relate to our surroundings, how we create meaning, and how we stay connected. My work often lingers in the space between distance and belonging, tracing the fragile threads that bind us to the environments we so often forget we’re part of.

“Having been exposed to so many opposing circumstances also taught me how fluid identity can be, how much we’re shaped by the places we inhabit”

Lena C. Emery

How did that nomadic upbringing shape your work?

It mostly fuelled an already excessive curiosity, but also shaped this enduring sense of existing between worlds, not fully anchored to one place, one culture or one way of seeing the world. It taught me to question everything because what appears so normal as a thing to do in one place or culture, somewhere else is frowned upon or might not even exist. That fragmentation is something I return to often in my work. Having experienced so many contrasting circumstances also taught me how fluid identity can be, how much we’re shaped by the places we inhabit, how natural and important it is to evolve, adapt, and sometimes not knowing where you belong, not occupying this one track mind, although challenging, can create worlds that are so much more connected. I feel that photography suits that way of thinking so much, it gives me the freedom to let the process shift and to keep finding new ways to speak to the same deeper questions.

Your series "The Mountains Between Us" — could you tell me about that location and experience?

The idea for The Mountains Between Us began with a conversation with the brand Tekla about how to raise funds in a way that felt sincere and emotionally resonant, while in keeping with the brand’s identity to raise funds for the environmental charity ClientEarth. Around that time, I kept coming back to an article I’d read about Okjökull, the first glacier in Iceland to be officially lost to climate change.

As I started researching, I came across these strange and moving scenes of the Rhonegletscher, once Europe’s largest glacier and now merely the fifth largest in Switzerland, being wrapped in fabric in an effort to slow its melting. There was something so stark in that gesture, this attempt to shield something vast and ancient with something so human and provisional. It felt like a metaphor for so much of how we respond to ecological crises. We’re reaching for solutions, often with real care, but always within the limits of what we’ve already broken.

Visually, the covered glaciers began to resemble tents or temporary shelters, fragile forms huddled in the landscape, echoing those displaced by environmental collapse. The vulnerability of those peaks mirrored our own. There was grief in it, but also tenderness. The title The Mountains Between Us grew from that. Mountains often stand for division, for distance. But I began to wonder if they could also be seen as points of connection, shared thresholds, places where different stories and responsibilities meet.

As an environmental photographer, are you noticing changes in the world due to climate change?

Absolutely. Just standing on the Rhonegletscher in 2021, knowing that others before us witnessed something very different and that future generations might never see it at all, was deeply affecting. Last year, while working on another project with Atmos in the Arctic, we were shown a series of maps that charted how the summer pack ice has receded by over 12 percent each decade since 1979. It’s one thing to read that in a report, but standing there, seeing it mapped out in front of you and witnessing firsthand how it is disrupting the wildlife that depends on it, was really devastating. But it’s happening everywhere. Here in London, at the local tree planting initiative that I volunteer with called the Treemusketeers, in the last few years we’ve watched things like the spindle ermine moth take over whole trees like never before. Warmer winters now mean more of the moths survive, and their natural predators can’t keep up. I also remember hearing Kevin Martin, the Head of Tree Collections and Arboriculture at Kew, at a talk speaking about how the 2022 drought wiped out over 400 of their trees and that more than half of the collection is now at risk due to rising temperatures. For someone who watches closely, I think what unsettles me most is how visible it all is if you’re looking, but most people still look away.

You also shoot fashion. How does that experience compare to your environmental work?

Conceptually, it differs from my environmental work in that it requires more direction than observation, but I approach both with the same instinct to uncover something meaningful and at the very least honest. There’s a different energy in working in large, collaborative groups versus on your own, but I try to focus on bringing the same curiosity and respect to both worlds. If anything, the intersection between the two is what I find most interesting and where the biggest potential often lies. Industry urgently needs stronger ethical and environmental values, but similarly the environmental field can benefit hugely from the reach, resources and tools that commercial platforms have perfected. In that way I feel like I can bring something and make a difference in both areas. I also believe that sometimes the most effective work is done outside our own echo chambers, in places where you might find the most pushback is sometimes also where you can affect the most change.

“The images we release into the world carry power, they can perpetuate harm or shape change. Your work has so much more potential to influence than you realise”

Lena C. Emery

We live in such a visual world now. What advice would you give to a young photographer just starting out?

Start with what moves you and don’t get lost in the scroll. The images we release into the world carry power, they can perpetuate harm or shape change, remember that you have so much more potential to influence than you realise.