How Today’s Pollution Will Become Tomorrow’s Fossils

In Discarded, Professors Sarah Gabbott and Jan Zalasiewicz explore how our trash and everyday objects will decay and disappear – or be preserved as new kinds of fossils in the deep, geological future. In this guest post, they explain some of their key findings.

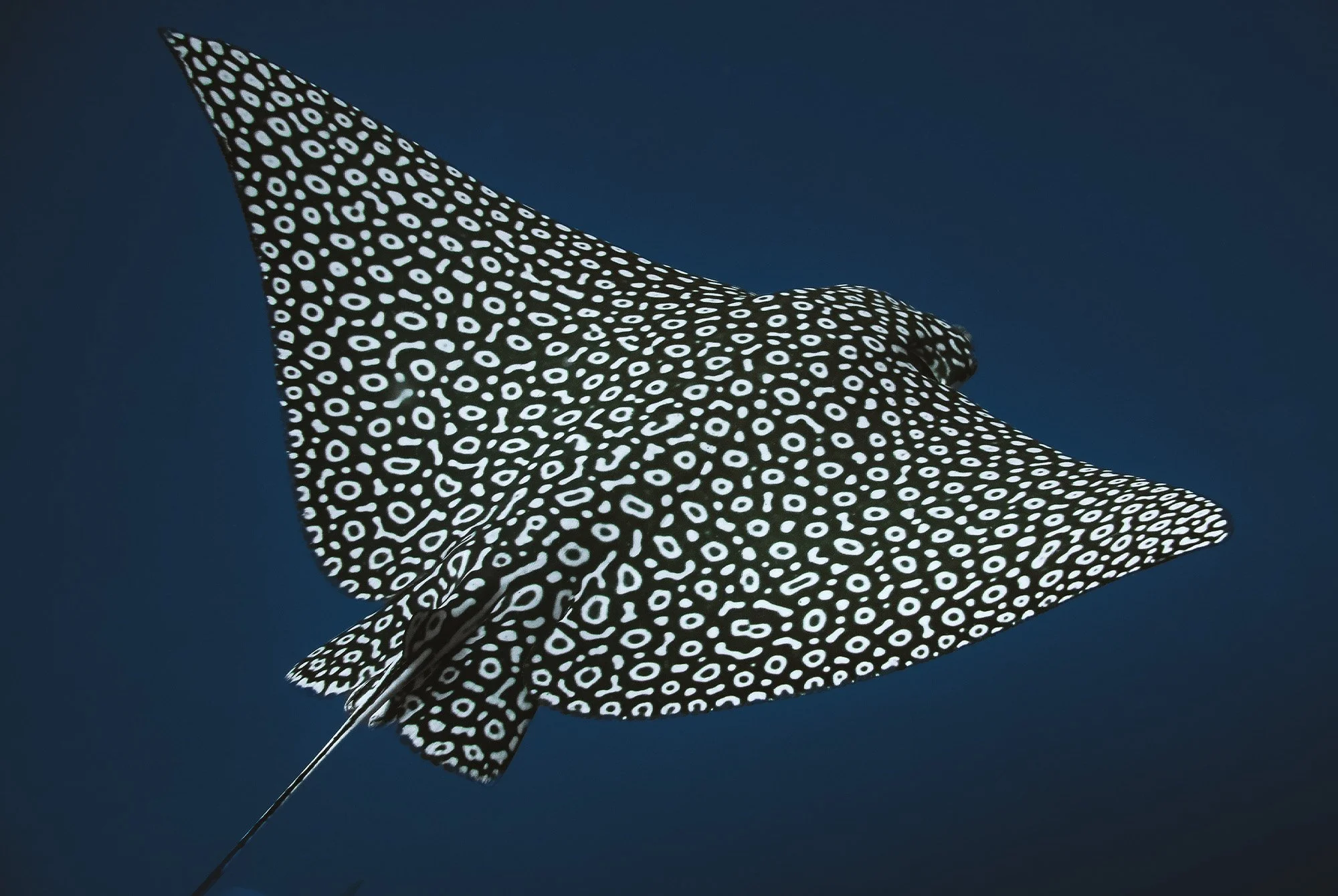

Photograph: Sarah Gabbott and Jan Zalasiewicz

We’re palaeontologists, and have spent our careers looking at the fossil record of the deep past, puzzling out how those magnificent animal and plant relics have been preserved as dinosaur bones, the carapaces of ancient crustaceans, lustrous spiral ammonites, petrified flower petals and many more. Often they still have exquisite detail intact after millions of years.

We’ve now turned our attention to the myriad everyday objects that we make and use, to see what kind of future fossils – we call them technofossils – they will make. The first things that’ll catch the eye of any far-future palaeontologist are our manufactured objects – buildings, roads, machines and so on. In recent decades, they have rocketed in amount to over a trillion tonnes, to now outweigh all living things on Earth. That’s a lot of raw material for generating future fossils.

Most things we make are designed to be durable, to resist corrosion and decay, and are significantly tougher than the average bone or shell. Just from that they have a head start in the fossilization stakes. Many are new to the Earth. Discarded aluminum cans are everywhere, for instance, but to our planet, they’re a wondrous novelty, as pure aluminum metal is almost unknown in nature. In the past 70 years we’ve made more than 500 million tonnes of the stuff, enough to coat all of the US (and part of Canada) in standard aluminum kitchen foil.

What’s going to happen to it? Aluminum resists corrosion, but not forever. Buried underground in layers of mud and sand, a can will slowly break down, but often not before there’s a can-shaped impression in these new rocks, lined with microscopic clay crystals newly-grown out of the corroding aluminum. Having been shielded from ultraviolet light, the thin plastic liner inside the can may endure too. (Oil-based plastic is even more novel in geological terms, being entirely non-existent until the 20th century). These two materials compressed side-by-side represent future fossil signatures of our time on Earth.

“Most things we make are designed to be durable, to resist corrosion and decay, and are significantly tougher than the average bone or shell. Many are new to the Earth.”

Sarah Gabbott and Jan Zalasiewicz

But what about bones – the archetypal fossil relic? There will be many of these as future fossils, stark evidence of our species’ domination over others. The standard supermarket chicken seems mundane. But it’s now by far the most common bird of all, making up about two-thirds of all bird biomass on Earth, and its abundance in life increases its fossilization chances after death.

We stack the odds further by tossing the bones into a plastic bin-bag, that’s then carted to the landfill site to join countless more bones for burial in neatly engineered compartments – also plastic-lined. There, the bones will begin to mummify, another useful step in the road to petrifaction. Our landfills are giant middens of the future and will be stuffed full of the bones of this one species.

These bones – super-sized but weak, riddled with osteoporosis, sometimes fractured and deformed – will tell their own grisly story. Future geologists will puzzle over a suddenly-evolved bird so abundant yet so physically helpless. Will they figure out the story of a broiler chicken genetically engineered to feed relentlessly to maximize weight gain, for slaughter just five or six weeks after hatching? We suspect the fossil evidence will be damning.

Photograph: Sarah Gabbott and Jan Zalasiewicz

Fossilizeable fashion is also new. Humans have worn clothes for thousands of years, but archaeological clothes discoveries are rare, because made of natural fibers they are feasted on by clothes moths, microbes and other scavengers. Fossil fur and feathers are rare too, for the same reasons.

But cheap, cheerful and hyper-abundant polyester fashion is quite different. There’s no need for mothballs with these garments because synthetic plastics are indigestible to most microbes. How long might they last? Some ancient fossil algae have coats of plastic-like polymers, and these have lasted, beautifully preserved, for many millions of years. Fossil clothes will surely perplex far-future palaeonologists, though: first to work out their shape from the crumpled and flattened remains, and then to work out what purpose they served. With throwaway fashion, we’re making some eternal puzzles.

The recipe for concrete, involving furnace-baked lime, is rare on Earth (the minerals involved occasionally form in magma-baked rock), but humans have made it hyper-abundant. There are now more than half a trillion tonnes of concrete on Earth, mostly made since the 1950s – that’s a kilo per square meter averaged over the Earth. And concrete is hard-wearing even by geological standards: most of its bulk is sand and gravel, which have been survivors throughout our planet’s history.

There’s nothing old about computers and mobile phones, but they are based on the same element – silicon – that makes up the quartz (silicon dioxide) of sand and gravel. A fossilized silicon chip will be tricky to decipher, though: the semiconductors now packed on to them are just nanometers across, tinier than most mineral forms geologists analyze today.

But the associated paraphernalia, the burgeoning waste of keyboards, monitors, wiring, will form more obvious fossils. The patterns on these, like the QWERTY keyboard, resemble the fossil patterns seized upon by today’s palaeontologists as clues to ancient function. That would depend on the excavators, though: fossil keyboards would make more sense to hyper-evolved rats with five-fingered paws, say, than superintelligent octopuses of the far future.

It’s fun to conceptualize like this, and set the human story within the grand perspective of Earth’s history. But there’s a wider meaning. Tomorrow’s future fossils are today’s pollution: unsightly, damaging, often toxic, and ever more of a costly problem. One only has to look at the state of Britain’s rivers and beaches.

Understanding how fossilization starts now helps us ask the right questions. When plastic trash is washed out to sea, will it keep traveling or become safely buried, covered by marine sediments? Will the waste in coastal landfill sites stay put, or be exhumed by the waves as sea level rises? The answers will be found in future rocks – but it would help us all to work them out now.