Loyiso Dunga: A view from inside the Great African Seaforest

In this interview we go deep on the marine biologist’s work mapping kelp forests on the coast of South Africa, why respecting Indigenous teachings is so important and how his fear of the ocean manifests itself as deep respect

When I connect with Loyiso Dunga over Zoom he’s even busier than usual, having just moved house with his family. Not that you’d know it from his relaxed, cheerful demeanor – Loyiso’s voice and worldview has a calming influence, a tranquil aura that’s almost meditative, particularly when he’s instructing me via video to close my eyes and imagine the Great African Seaforest as he describes it in detail. If he ever gets fed up with marine biology, a career in ASMR voiceovers awaits.

Loyiso lives with his family in Cape Town, South Africa and in 2016 he embarked on a mission to map what’s now known as the Great African Seaforest (more on that name later). You may have come across the forest yourself without realizing it if you’ve seen the Oscar-winning documentary My Octopus Teacher, Craig Foster’s story of freediving amongst kelp and in the process developing a strong bond with a female cephalopod. The forest is a kelp ecosystem over 1300 km long that stretches along the coast of Cape Town into the shores of Namibia. It’s the only forest of giant bamboo kelp on Earth, a unique area of thriving biodiversity that’s home to thousands of species. While other kelp forests around the world are declining, the Great African Seaforest is expanding, although Loyiso isn’t exactly sure why this is.

When we think of expansive rainforests like the Amazon, or behemothic natural wonders like the Grand Canyon, they’re visually firmly established in our minds. Even though kelp forests play a vital role in maintaining the planet’s stable climate through sequestration of carbon and removal of nutrient pollution, they haven’t benefited from the same PR. This is why Loyiso and other local scientists rebranded this vast stretch of kelp as the Great African Seaforest, to ensure that it’s treated globally with the gravitas that it deserves. Loyiso’s work mapping the Great African Seaforest during his master’s degree changed the trajectory of his life – prior to the project beginning he’d never encountered a kelp forest. His scientific curiosity led him to the water and today he enjoys a deep connection with the forest, a reverence and respect that’s inspired by a childhood being taught to maintain a healthy fear of the ocean.

Here, Loyiso reflects on his work as a marine biologist, what he learned from his grandfather’s life as a traditional healer, the barriers that still need to be overcome in South Africa, and the hope of everything we stand to gain by respecting Indigenous teachings.

“I have that reverence for the ocean but I am an inquisitive scientist, I want to know more, I want to explore. It's that balance for me – I'm afraid of the ocean because it's sacred.”

Loyiso Dunga

Q & A

What would you describe as being your life's mission?

My life's mission is to explore as many different pathways as possible for us to come together with a common heart – different races, different age groups, different genders. I want us to work together in order for us to make better decisions that are not going to only protect our ocean today, but to ensure that future generations get to enjoy, be mesmerized, see the wonder, to be immensely connected to these spaces because they are truly sacred. Think of it like this, someone safeguarded our ocean heritage and passed it to us, so it's a life obligation for us to do the same.

Can you describe the Great African Seaforest, to give someone an idea of what it’s really like?

It's located in the southernmost tip of Africa, to start with. We coined the name the Great African Seaforest for multiple reasons. But for me particularly, it's because that the biggest density of kelp forest that you find hugging the coastline of Africa, occurs here. The fact that we have a thriving ecosystem concentrated here means that it deserved a name that is as great as what it symbolizes. A lot of people can quickly imagine what the Amazon is about, and can quickly imagine what a rainforest is about. What I often say is: stick with that mental image that you've got now of what the Amazon is like, stick with it, in that deep silence, in those shadows, in the light penetrating the canopies, that earthy smell and chirping birds. And if you listen even more, you start to hear the crawling bugs and critters on the leaves, the dead leaves – hold onto that image – and then now you're going to be submerged underwater.

Slowly, the water is starting off at your feet, it's going up, it's going up over your waistline. You are completely safe, so there's no need to worry. Then the water submerges you and it goes even higher. When you open your eyes, what you see is exactly a similar place, but the forest is doing something even more amazing. It seems like it’s dancing. As the waves come, the kelp pushes to one direction, and then bends to the other direction and comes back. If you actually listen, you hear a similar sound to those chirping birds, like cricket sounds. You can even hear the individual kelps breathe. If you look around, you'll see different creatures going up and down the stipes, which are similar to the bark of a tree. The fronds, which are exactly like leaves, are sitting on top and preventing most of the light from coming in. When it does actually penetrate, you see these beautiful rays of light. There are a lot of fish swimming around you. Some will actually come close to you. So this is what the Great African Seaforest looks like in a nutshell. It is a home to a plethora of species. It safeguards not only us and our coastline, but a lot of biodiversity. That is why we gave it this honorary name – the Great African Seaforest.

Have you seen an increased awareness and help with the protection of the Great African Seaforest once you named it that. Do you find that people are understanding the power of it?

Certainly. I think because we gave it this magnificent name, it's drawn a lot of attention to it. I see different sectors here in South Africa that make a lot of reference to the Great African Seaforest, for example: "Come snorkel with us in the Great African Seaforest..." I'm seeing a lot of that. It seems like now more and more people attach a strong sense of place to the Great African Seaforest. So for us that is a certain win, but because the location of this magnificent forest inherits the complicated history of this place, there's still more we need to do to break those barriers, to help more people re-connect and create that sense of place for them. By mending that severed link, we actually break those historic barriers that were erected and disconnect people from what was truly part of their everyday life.

We still have a long way ahead in terms of ensuring that more people actually regain connection to the space. It's quite encouraging to see a lot of young people, a lot of diverse people interacting with the space. It's certainly a legacy project of hope, because it's incredible when you look at it and you see what it's going to become. The vision is that when I say ‘imagine the Great African Seaforest’, someone closes their eyes and exactly sees the same picture as when you imagine the Amazon – then they can see the beauty and the fragility, and therefore why we need to protect the Great African Seaforest. That's where we are going. Up until we reach that, we still have a lot of work to do in order to ensure that people are interested, connected and feel like it's theirs.

When you're talking about complicated history, do you mean apartheid?

Certainly. South Africa has seen bitter days. The shadow of and the legacy of apartheid still looms. This is creating an impediment in terms of the work we are doing to reconnect, because these people we are talking about are one with these places, they've always been one. Their ancestors are connected to these spaces but they've been painfully severed. So it's actually going back to those wounds and touching them and saying ‘trust me, it's OK. It's all going to be well." It's such an intricate and sensitive process on its own. Nonetheless, we are getting out, albeit slowly.

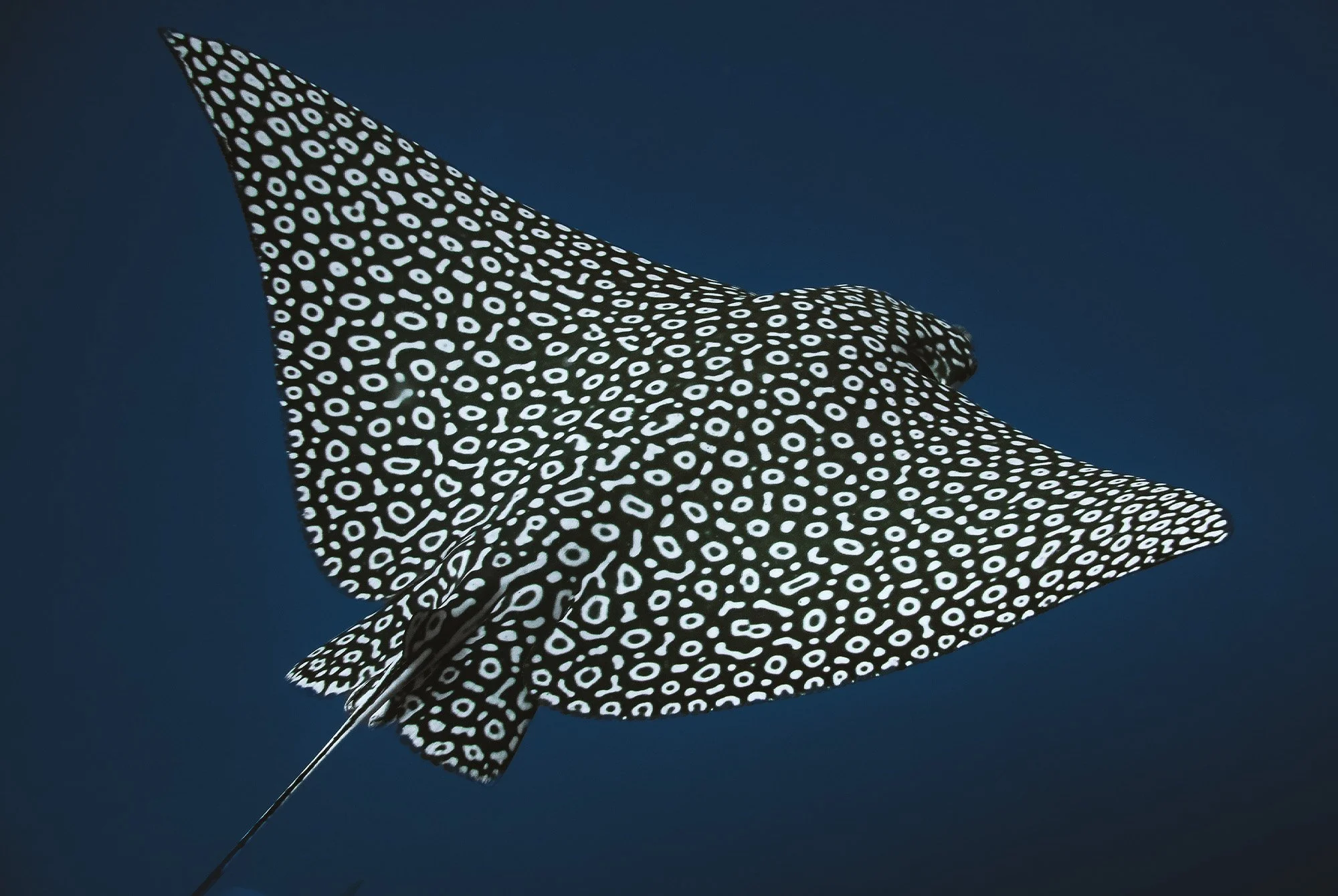

Photographer: Sacha Specker

“The vision is that when I say ‘imagine the Great African Seaforest’, someone closes their eyes and sees exactly the same picture as when you imagine the Amazon.”

Loyiso Dunga

What other challenges do you face – environmental or human – in your work to protect the Great African Seaforest, and how do you overcome them?

The first challenge is the fact that even though we are now becoming more and more excited about the Great African Seaforest, it is still very early days. We need a lot of funds to ensure that we shine the light of the Great African Seaforest, deepen its awareness here and beyond the shores of Africa, and ensure that it reaches the entire world. The name is fairly new and a lot of people are yet to grapple and understand or even imagine it.

One of the best ways to overcome challenge number one is to touch people's hearts before speaking to the profession and expertise. The approach will ensure that we reach the person's heart and then you produce scientific evidence showing the reasons why we need to safeguard this space. Back this with Indigenous knowledge and then the magic happens. These are the approaches that we are carefully designing.

It becomes an interdisciplinary process because science alone is not enough, social sciences alone are not enough, and now Indigenous knowledge alone may also not be enough, so we need to weave these things together to ensure that we reach as many people as we can, and get all the help we need to get this right.

There are a lot of reports in the news about decreased biodiversity in marine ecosystems. Is that something you notice there or is it flourishing? What's the state of play there?

We know that globally there's a lot of decline in kelp forests. We’re quite lucky in South Africa. We don't know why. For me, this is the caution. This is the reason that we need to up our endeavors to ensure that it's well protected. I'm saying this because we are actually seeing the kelp expanding along the southern coast. We are not sure what is exactly the reason for this, as we are seeing a lot of kelp disappearing in many places.

There's a recent publication I read that hit home. In Oman, kelp forests that were seen by locals about 25 years ago are nowhere to be found today. People can go to the coastline and say, "There used to be kelp forests here, we don't know what happened to them. They are not there." And that's very close to Africa. So for me, it's like a wake-up call. Although we are seeing this expansion, we need to put more measures into place to ensure it's well appreciated, it's well understood, and well protected.

You developed the first comprehensive map of South Africa's kelp forests. Can you tell me a little bit about how you did that? And is the mapping project still ongoing?

For my master's degree, by building on top of existing scientific data I was able to develop an up-to-date (and then a more comprehensive) kelp forest ecosystem map for the coastline of South Africa. It was such a phenomenal project for me. If it wasn't for that project, I wouldn't have been enchanted by the forest, because it started as a project that required me to sit on my desk and use remote sensing, which operates just like a bird's eye view, on its path and taking snapshots of the kelp forest beds. That's all I needed to do. But I was drawn to the forest out of curiosity and the sense of, "What is this thing that I'm mapping?".

Prior to this work, I had never encountered a kelp forest. I would've seen it dead on the beach but it never raised an alarm for me – I didn't understand what it was, and I was not curious enough to find out more. (I am sure it is what occasionally would wrap around my leg and scare the life out of me on the occasion I waded into the ocean?). The project required me to take these images and then analyze them based on the chlorophyll content. This allows us to establish where vegetation or plant life is thriving. What was innovative is that we used datasets from a single satellite. It was not like you have an iPhone, someone else has an Android and someone else has a different device, then we take different pictures and try to mosaic them together to develop one picture. It's always going to be inconsistent because of things like incompatible resolution. What we were able to do with this work was develop imagery of the kelp forests, stretching over 1300 km, and then we analyzed the content.

For me, that work was the first step, and needs to continue. However, because I've stepped into a different role, the work is not going as fast. I don't have a lot of time on my hands to dedicate to that work at the moment. But raising the profile of the Great African Seaforest is also a means to attract passion, young talent and funding to enable them to take this work forward. Currently, what we have is a snapshot of that kelp, what we need is a continuous monitoring of how it looks in – different months, different seasons, different years. Then we'll get a better understanding of how it is doing.

Because of your mapping project, when you are swimming there do you kind of know your way around, like I might when I walk through a city?

It's such a maze, that's the incredible thing about the kelp forest ecosystem. I haven't swam or snorkeled in most of the kelp that I've mapped. Each and every time I go to a new location, I know I'll find kelp. But as soon as I plunge, it's always different. The spot that I always go to is actually featured in the movie My Octopus Teacher. What is profound for me is going into the same spot – the reason that I do that is because it’s safer. It's often always surprising. It's moving. I go to the same place, but it's a different chapter. Sometimes I see the kelp standing erect, not dancing as much as they were dancing the previous days. Or sometimes I can't see anything because there's a lot of sediment in the water. Sometimes there's so much surge that I'm pushed out and out and far from the safe space I know. It's an incredible feeling. If you go to a forest, you can ground yourself and stand there. You can't do the same in a kelp forest. It's going to splash you, it's going to slap you, it's going to push you. You seldom find yourself in one space.

You just mentioned that you go to the same location a lot because it's safe. What dangers are you talking about when you're swimming in the Great African Seaforest?

I'm sure that question is different for different people. My relationship with the ocean is quite interesting I suppose, I seldom put it into words. I'm a marine biologist. I grew up culturally revering the ocean. Up until my 20s I used to be afraid, dead afraid of the ocean. I was cautioned about its might. When I was in grade two, a few of my friends skipped school, went to the ocean and then one of them actually drowned. It was a validation of the cautions I grew up with. I have that reverence for the ocean but I am an inquisitive scientist, I want to know more, I want to explore. It's that balance for me – I'm afraid of the ocean because it's sacred. When you walk through a graveyard, your spirit has a different demeanor. The ocean for me has a similar setting. As soon as I enter the ocean, how I perceive myself in relation to the environment changes completely. The biggest fear for me is that I'm in a sacred space. Am I being allowed to enter this space? Am I pure enough inside? Because most of the time it literally reflects how I'm feeling. In times of turmoil, I seldom enjoy swimming. I seldom enjoy exploring or being in the ocean. But after that experience, I feel calmer. I feel that I can reconnect to myself. So it's that. It's that. I'm constantly aware of how minute and how insignificant I am in this space, and out of place, because it's not my territory.

I love the kelp forest because it gives me that protection. As long as I can hear the kelp rubbing against me, I know no creature is coming to investigate me. In our waters, we have the great white sharks, we have orcas, we have whales, so we have seals, sea dogs. I have a thing with dogs. I'm quite afraid of them. So imagine sea dogs - it's two times the fear! Anything that moves faster than me in the ocean makes me think "You know what, I know my place. I'll stay. I won't approach.”

I want to talk about how your work combines both scientific research and Indigenous teachings. How important is it that these two knowledge systems work together as we try to protect the future of our planet?

Thanks for that question – it's very close to my heart, as it's actually intertwined with my DNA. I alluded in the beginning of our chat to the idea that what we've got now, we've inherited. Someone would've employed norms, customs and principles to ensure the future, what we have today. For me, the role of Indigenous knowledge is very core. Sometimes I become frustrated with the world for underestimating this because there is no way that our ancestors have taken care, safeguarded these things and passed them down to us for no reason.

For us to take the same inheritance and discard the knowledge that has brought it forth to us, for me, often that's what makes me feel like the world needs to really recognize the power we are missing. We are doing science a huge disservice because it means we end up developing data, we end up reaching conclusions that are far from reality and that are hugely incomplete. It's extremely important that Indigenous knowledge and science are in tandem with each other. It's not a matter of which one is greater than the other. That's not the focus. Steel sharpens steel and these are both steels, so each one remains blunt without the other. For the work we are doing in the Great African Seaforest, we've got caves that look out into the ocean and there are shell middens there that show us how our ancestors were interacting with these spaces. Shell middens are piles of shells and bones – often it's almost like a kitchen where someone sat, ate and left everything there, so they piled up. When you explore them, it's out of this world just to see how much our ancestors were dependent on these systems and how we have inherited them. I'm a scientist, but I grew up in a household with a man (Loyiso’s grandfather) who is a traditional healer, who uses marine species to heal people in my community, in my village. This Indigenous knowledge has been passed to me and my brothers and we carry it wherever we go. I understand the science that we need to ensure that we leave thriving kelp forest ecosystems, not only those standing golden beautiful plants, but the entire ecosystem – that's what we need to preserve. When I think about that, plus everything that I was taught and how they come together in harmony, I think that's what the world needs to realize more and more.

“The role of Indigenous knowledge is very core. Sometimes I become frustrated with the world for underestimating this because there is no way that our ancestors have taken care, safeguarded these things and passed them down to us for no reason.”

Loyiso Dunga

You mentioned that your grandfather was a traditional healer. Could you tell me a little bit more about that?

I often like to start with this disclaimer: it's not as glamorous as it sounds. To actually be a daughter or a son or a grandchild of a traditional healer is quite hectic. It's quite an intense experience. My parents experienced it much more than I do because you know how grandparents have soft spots for their grandkids. So I'll start there. My grandfather would have visions at night and wake up at 2:00 AM in the morning, he'd go out of the house, either into the forest or to the shores. It's quite a terrifying experience if you are young and you wake up in the house and someone looks like they are sleepwalking, disappearing into the distance, then your parents say, “No, it's OK.”

Then he comes back with what looks like debris or dead animal skin. Then he sits in seclusion for a couple of hours. Then that very same day, someone sick comes. It's either a cousin, an uncle, or a relative and my grandfather has a medicine that he’s already mixed together for them. He'll tell them, “You have this. You are suffering from this. You can't sleep. You're having this, this is what you should be taking.” That is how he uses a lot of marine species. There are various ones that are largely used in Africa actually, not only by him, but for example jellyfish. They were quite potent during times of war, so were used by a lot of African tribes to strengthen the warriors as they went to war. But there are a lot of different animals used. It is a miracle to witness but also a very powerful way to be in harmony with nature because then you understand why the sea turtle holds reverence in your family.

What advice would you give to somebody who isn't sure how to play a role in protecting our planet but wants to?

I will go to the principles of Indigenous knowledge to unpack that. I'd say what has made this mission much more easy, is the principle of Ubuntu. Ubuntu, if we translate it to English, means humanity. It's an celebrated and known proverb in Africa, which says ‘I am because you are’. By embracing that, I'm naturally able to sympathize with my kin because my environment is my kin.

I would say for someone that is curious, it's really that principle of life. If you take care of your neighbor, if you take care of your trees, if you take care of the spaces around you, if you reciprocate that humanity, you receive and you give. That's where we need to all get to, because that way when you interact, when you're in a forest, you gain from it, but you ensure that you don't destroy it.

We are all in different expertise and careers and groups. When you in your organization see tons of plastic going into places that you think it shouldn't be, then you already have that connection, understanding and respect – and then you intervene. So for me, I think it's very simple. I think it's your heart.