THE INVISIBLE THREAT: MICROPLASTIC AND MICROFIBER POLLUTION

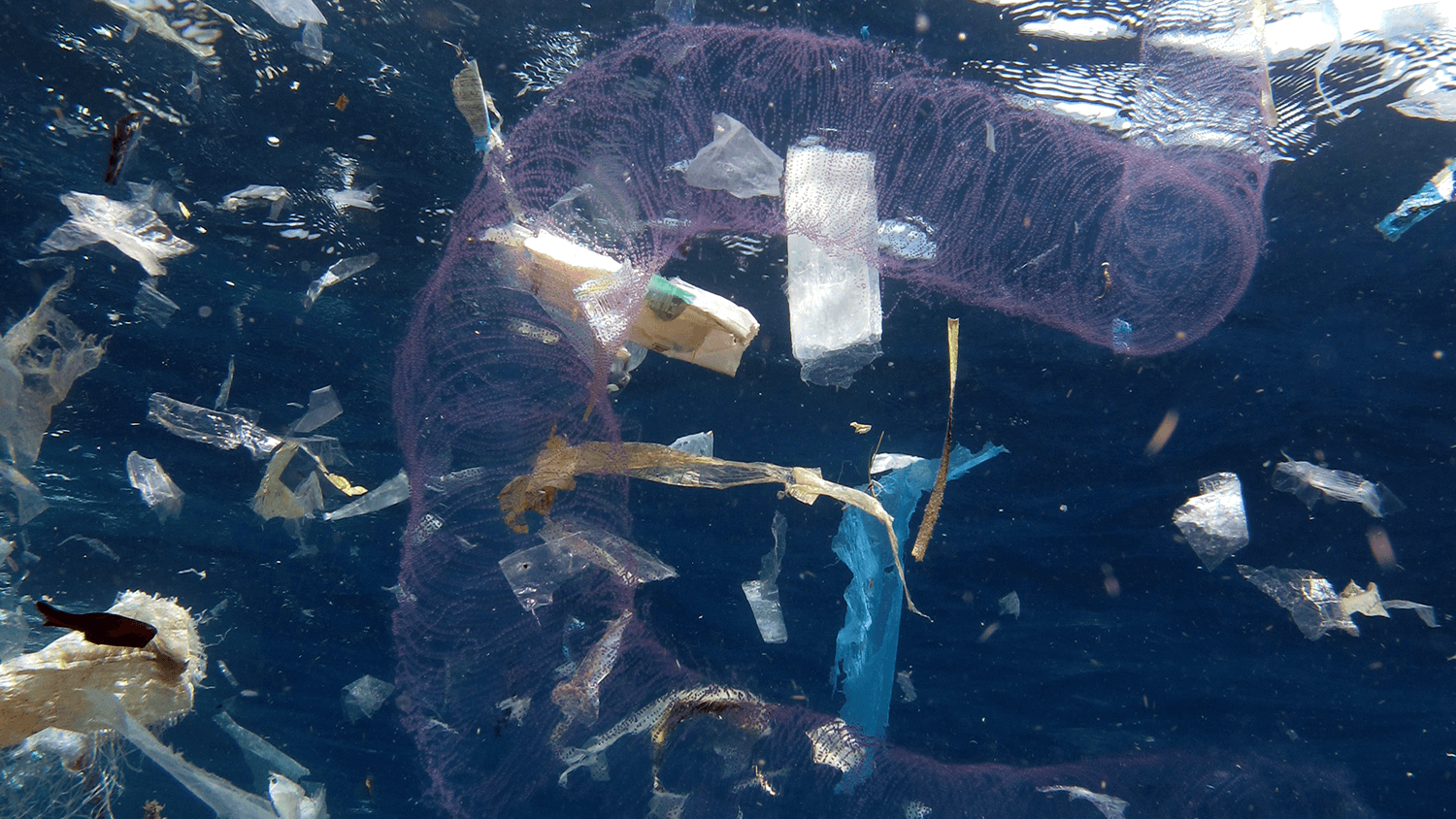

Plastic is everywhere – and what we can easily see and intercept is only the tip of the iceberg of a much larger and complex issue.

Plastic doesn’t break down and biodegrade. Instead, it continually breaks apart into smaller and smaller pieces that pervade every environment and even the smallest life forms. In the oceans, plastic photodegrades with exposure to the sun and surf, fragmenting into smaller and smaller pieces. Microplastics, defined as plastic pollution smaller than 5 mm in diameter, are now spreading through waterways, lakes, rivers and streams. Joined by even smaller nanoplastics, this almost-invisible form of pollution has spread like a toxic smog into our soil, water, snow, ice, plants and even the air we breathe. From the highest peaks of the Himalayas to the bottom of the Mariana Trench, from table salt to bottled water and now inside us – it’s everywhere.

Although it’s the smallest form of plastic pollution, microplastics and nanoplastics may actually pose the biggest threat. Alarmingly, a 2001 study by Japanese researchers found a single plastic pellet can be a million times more toxic than surrounding seawater. Perhaps even more unnerving is how much virgin plastic the world has continued to produce since then, and how little has been recycled. Half of all plastic to ever exist was made within the past two decades. Only about 9% has been recycled.

There are actions and strategies underway to address this problem, and early innovations available for consumers to help curb the threat. Still, the full extent of the issue remains poorly understood and difficult to address. One of the biggest challenges of the Material Revolution will be tackling the unseen microplastics and synthetic microfibers. Together with a global alliance of researchers, material experts and environmental groups, Parley is working to consolidate existing knowledge and develop new tools and methods to end this form of pollution and replace plastic for good. Understanding the problem is an imperative first step towards fixing it.

WHAT ARE MICROPLASTICS?

Classified as pieces of plastic in the environment less than 5mm in diameter, microplastics exist in varying shapes, forms and sizes and come from various sources. Primary sources include particles designed for commercial use (e.g., resin pellets, microbeads in cosmetics and fibers shed from clothing and fishing nets), while secondary sources include particles that break apart from larger pieces of plastic, like plastic bottles. Any piece of plastic is a potential source of microplastics.

The five main types of microplastics

Fragments

tiny pieces of plastics that photodegrade (and break off) from larger pieces.

Microbeads

tiny plastic particles used as exfoliants or scrubbers in personal care products, including body washes and toothpastes that escape wastewater systems and slip out to sea.

Foamed plastic particles

materials used in packaging, cigarette filters, etc. Cigarette butts are the most common form of litter found on beaches around the world.

Nurdles

pre-production plastic pellets used in the manufacturing of plastics.

Microfibers

fibers which shed from tires, fishing nets and textiles made from synthetic materials (e.g., polyester, nylon, acrylic) with wear and tear, or in the wash.

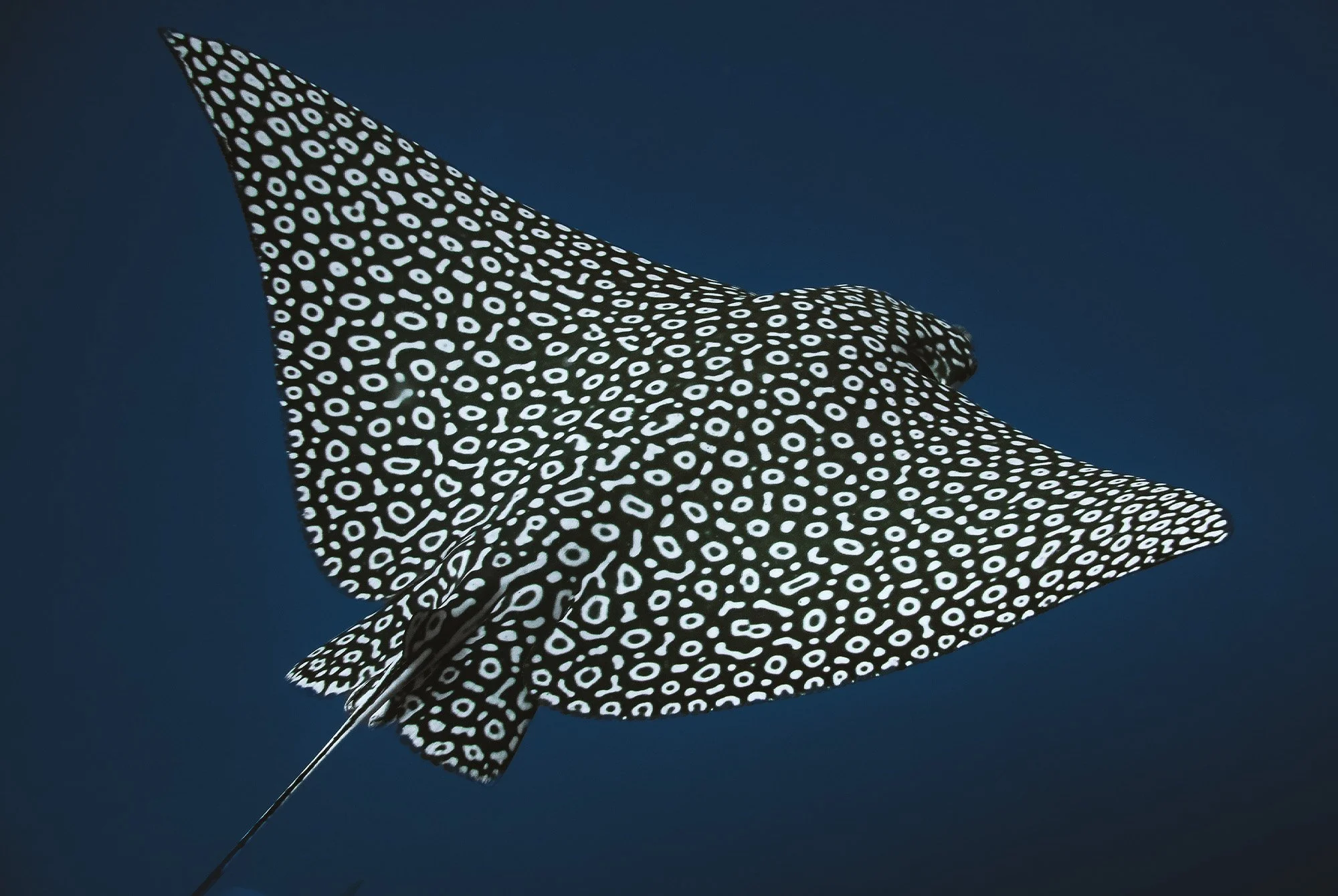

All forms of plastic pollution pose a major threat to the environment, wildlife and potentially human health. Research indicates microplastics attract and absorb chemical pollutants in the water and are easily ingested by marine life. Large filter-feeding species like whale sharks are especially vulnerable, gulping up galaxies of plastic with every mouthful of seawater. But even the tiniest sea anemones, coral polyps and zooplankton are swallowing our synthetic waste. Studies have found that when transferred to tissues in marine species, these contaminated microplastics can leach harmful chemicals causing endocrine disruption, liver and organ damage, which raises the question about the impacts on all of us.

Studies show we are ingesting at least 50,000 pieces of plastic every year through contaminated products, such as seafood and plastic bottles. Microplastic particles are in the air we breathe, and plastic microfibers have even been found in human placentas (read our report on the links between plastics and women’s health here). More research is needed to understand the effects of plastic on human health – but generally speaking, if it isn’t good for the planet, and made with chemicals linked to hormone disruption, reproductive issues and cancer, it’s probably not good for us.

HOW PREVALENT ARE MICROPLASTICS?

In 2011, Parley collaborator and ecologist Dr. Mark Anthony Browne sounded the alarm about tiny synthetic fibers from clothing washing up on beaches. More recently, a European study found that 550,000 metric tons of plastic particles smaller than 0.01mm from car tires are deposited on roads each year, with almost half ending up in the ocean. Carried on the wind, more than 80,000 tons of tiny black plastic specks fall on remote ice- and snow-covered areas – likely increasing snowmelt as the dark particles absorb the sun’s heat. Scientific knowledge of this ‘plastic smog’ threat is ever-growing, but the global consensus is clear: plastic microfibers are shockingly prevalent in both aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems. In recent years, scientists have made a number of worrying discoveries:

A study found there may now be more microplastic blowing out of the ocean at any given time than there is going into it. That means so much plastic has accumulated in our oceans that they have become a source of microplastic pollution to other regions.

As many as 51 trillion tiny pieces of plastic now litter the seas, which means there are 500 times more microplastics in the oceans than stars in our galaxy.

Microplastics pollute virtually every crevice on Earth.

It’s estimated that there are 1.4 million trillion microfibers in our oceans (based on a number extrapolated from this study) — or the equivalent of about 200 million microfibers for every person on Earth.

An estimated 0.6 – 1.7 million tons of microfibers are released into the oceans every year.

During the all-female 2018 eXXpedition led by Parley collaborator Emily Penn, a single sample of ocean water from the North Pacific Gyre hundreds of miles from shore contained over 1,000 pieces of microplastic.

Cigarette butts are the most common form of litter found on beaches around the world. They are typically full of microfibers and toxic chemicals.

Close to a third of microplastics in the oceans come from tire abrasion. Other major contributors include the apparel industry and fishing nets.

More than 200,000 metric tons of tiny plastic particles are carried on winds from roads to the oceans every year.

WHAT ABOUT CLOTHING MADE FROM RECYCLED PLASTIC?

It’s well-established that textiles made from synthetic materials are a source of microfiber pollution in waters and the environment, shedding from clothing at every stage — from manufacturing, to wear, and in the wash. Research shows the problem is also prevalent in fabrics made from recycled polyester materials, which have rapidly gained popularity as brands seek ways to avoid and replace virgin plastics. As with every step in the journey to long-term solutions, understanding the full ecological impacts of any product or material is far from straightforward.

Transforming plastic waste into Parley Ocean Plastic®, a range of premium materials, is an eco-innovation that allowed Parley to cast plastic pollution into the global spotlight, improve recycling processes, reduce reliance on fossil fuel-based virgin plastics, and rally the support of industry leaders like adidas. However, it’s vital to note that we do not see this as an end-all solution. Recycled or upcycled, plastic is still plastic, and together with our partners we want to move beyond it.

In the meantime, we’re careful with where and how we choose to introduce recycled plastics. Most high-performance sports gear cannot currently be made from natural fibers and achieve the same attributes. Meanwhile, a lack of industry standards, regulation and transparency cloud the fast-growing market of plastic alternatives. Materials marketed as “biodegradable” are not always better. While we work towards scaling innovations, developing a supply chain for the use of plastic debris intercepted from marine environments and coastal communities has allowed us to create fair jobs, raise global awareness, reduce fossil fuel emissions, create initiatives focused on education, cleanups and eco-innovation, and develop a funding model for the removal of even more plastic waste, which in turn protects more sea life.

Ocean Plastic® transforms products into Symbols of Change that champion our message and Parley AIR Strategy for a Material Revolution. Rather than a perfect response, it provides a catalyst for our long-term objective: to end plastic waste and ultimately, redesign and replace current plastic with materials that work in harmony with nature.

WHAT CAN WE DO ABOUT IT?

There are no easy solutions or magic fixes for this vastly complicated issue. Recognizing the complexity of the problem, Parley set forth a new approach driven by creativity, collaboration and eco-innovation. Parley AIR — Avoid, Intercept, Redesign — is our strategy to end marine plastic pollution and create and scale the future materials, products and systems that work in harmony with the ecosystem of nature. We believe Parley AIR can drive the Material Revolution and help end the threat of plastic pollution for good.

Avoid

Stop producing new plastics

Intercept

Remove immediate threats to sea life and upcycle plastic waste

Redesign

Reinvent and replace faulty materials, methods and mindsets

Some microplastics are easy to avoid. We can switch from single-use to reusable items to cut down on pollution from plastic bags, bottles, straws, utensils, cups and lids. We can demand and enforce bans on industrial fishing, remove plastic microbeads from personal care products, choose clothing made from biodegradable materials and make glitter and cigarette butt litter socially taboo. We can skip unnecessary car trips and push for eco-innovative alternatives to car tires. But how will we eliminate a problem of this scale that we can’t even see?

Plastic microfibers present an unprecedented challenge. To end this threat, we need to end the material. We cannot keep plastic, in its current form, in a closed loop. That’s why we are calling for a Material Revolution. As scientific understanding of marine plastic pollution deepens, public awareness grows. Although the threat has risen in the global consciousness, solutions that can be globally implemented and scaled remain elusive. And more science is urgently needed to establish new standards.

PERSONAL WAYS TO LIMIT MICROPLASTIC POLLUTION:

Avoid the use of plastics wherever possible, as all plastics break apart into smaller and smaller pieces.

Avoid single-use plastics bottles, bags, straws, etc.

Limit vehicle use — carpool, use public transit, bike or walk as much as possible.

Shine without plastic glitter. There are biodegradable alternatives.

Avoid purchasing or using products that contain microbeads. Scan ingredients labels for words like polyethylene (PE) or polypropylene (PP), polyethylene terephthalate (PET), polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) or nylon.

Support policies to ban microbeads in personal care products. Don’t wait until policies are enforced to banish products from your home.

Wear clothing made from natural fibers wherever possible.

Limit your clothing made from synthetic materials to items that you can launder less frequently. Wash on cold with liquid soap and hang dry or dry at low revs in the machine. Or try washing with innovations likes bags, balls and filters designed to help catch the microfibers.

Drive the Material Revolution. Invent a better material, filter or catcher system and participate in consumer activism to demand eco-innovative alternatives to the status quo.

The reality of microplastics is a massive, complex and global issue – one with ties to every industry. The only way to stop this invisible threat is together. Parley launched a Material Institute and is calling for a Material Revolution to accelerate research and connect leading experts and scientists as we work collaboratively to develop new tools and methods that can stop the pollution at its source. Read recent research we supported with Ocean Alliance here. There are currently products which can help filter plastic microfibers in the wash, but more research and more collaborative innovation is needed to develop, rigorously test and scale scientifically-backed solutions.