FASHION PHOTOGRAPHER DAISY WALKER ON RETURNING TO NATURE WITH HER NEW BOOK

For the latest feature in our In Focus series we discuss her new book Guardians & Carers Of The Natural World, a tribute to the majestic beauty of our world

Photographer Daisy Walker has been shooting fashion for the past decade, creating imagery for some of the industry’s biggest brands such as Loewe, JW Anderson and Burberry. Going through her portfolio you can see distinct threads emerge – a sensual care for the human body, a powerful sense of femininity and a strong connection to the environment. It’s this last pillar that inspired two areas of seismic change in her life. Walker left London and moved to the countryside, desperate to reconnect with the stillness of her upbringing on the rural outskirts of England’s capital city. It’s here that she says she gets her energy – from the sound of animals, the touch of a breeze, or the sight of a scurrying insect.

She also recently released a book called Guardians & Carers Of The Natural World, a tribute to the majestic beauty of nature and people that have immersed themselves within it, living lives of relative solitude and enjoying a reciprocal relationship with our planet, rather than the parasitic approach that modern civilization forces our environment to endure.

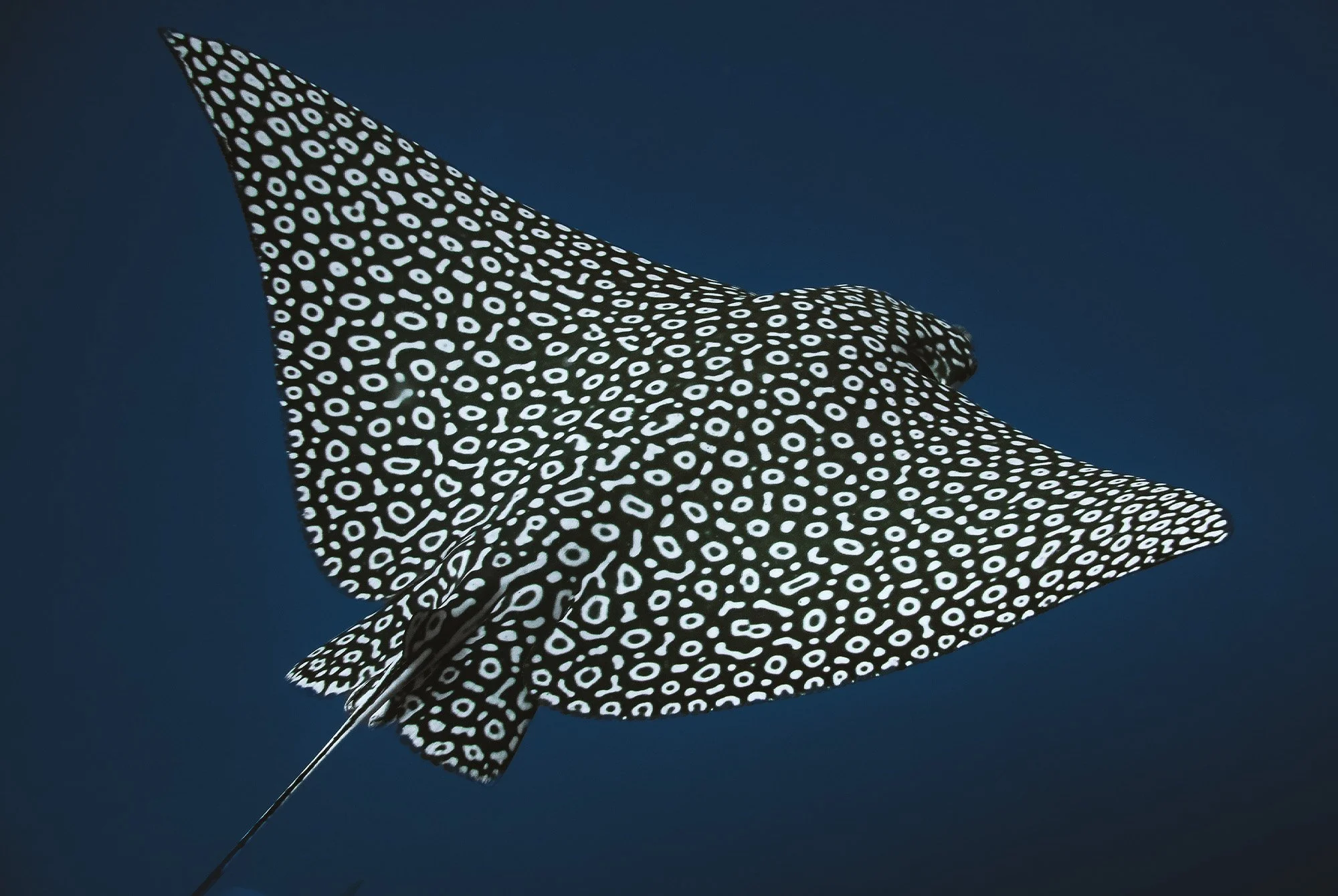

The limited edition book contains various viewpoints of nature in different states, shot by Walker over a period of two years. There’s a shark pressed up against a tank in the London aquarium, a stunning image of snowy mountains, people on horseback making their way across sandy terrain, printed alongside testimonies from people who have returned to the wild. For the latest feature in our In Focus series, we spoke to Walker about her motives for making the book, her departure from urban living and interconnectivity.

Q&A

In the book, you talk about your own upbringing around nature and how it was embedded into your life. Was that something that you ever felt that you lost living in a city, and wanted to reclaim for yourself through doing this book?

I've certainly felt removed from nature, and that side of myself through living in a city. Covid actually gave me the time to process that feeling and make changes in my life to be in nature more. We are privileged enough to have taken on horses and are now renting our own land. Making the book was more a response to what I had learnt about myself, and about the relationship between all living things, through researching land management and caring for our horses.

You've spent a long time working in fashion. I speak to a lot of people working in fashion who feel disenchanted with the industry's environmental impact – is that something you think about and was it a motivation for Guardians & Carers Of The Natural World?

It's impossible to not consider the fashion industry's environmental impact, but it's also easy to focus elsewhere and negate our own individual impact on the planet. It is the consumer who drives demand. We hold more power than we realize. My motivation for making 'Guardians' was the separatist view I saw played out about our relationship to the planet. Nature is us, and we are nature. But that truth has been lost amidst the chaos of deadlines, Instagram advertising, and constant media access. I wanted to reinstate a two-sided relationship between the natural world and us. Until we can rectify this disengagement, I don't see how lasting change is really possible.

For the book, you spoke to some people who'd turned their backs on city life and returned to nature. What was the overriding narrative that emerged from those conversations? Were people happy with their decision to leave urban life behind, and what had been the improvements to their lives?

Some of those I spoke to have lived in cities and turned their backs on them. Many of them had always lived in nature. But in none of them did I hear a pang for anything other than the life they had chosen. They had seen the light and couldn't wind back the clock and forget what they now know about how precarious our position is as a key player in the ecosystem of Planet Earth. We didn't speak in selfish terms about what they 'get' from living in and with nature. That in itself is the wrong way to look at it. Perhaps we should all be considering more what we can offer nature, than what nature can offer us?

“Nature is us, and we are nature. But that truth has been lost amidst the chaos of deadlines, Instagram advertising, and constant media access.”

Daisy Walker

A lot of people I speak to in my work at Parley make the point that we talk about nature as though it's something separate to us, that we aren't part of. I think it's true that we've created this disconnect. How do you think we get it back?

My aim with 'Guardians' was to draw on passion, to draw on emotion. We all know the facts, we know about deoxygenated oceans, dwindling biodiversity and so on. Yet changes (micro and macro) simply aren't being made. In order to ask people to really change their lives, I think you have to draw on emotion. People will do an awful lot for the things they love. I wanted to inspire or reinvigorate a love and passion for the natural world.

I work in Sweden a lot and find the people there on the whole, much more connected to nature. It's normal to not live in the city, but an hour or so out and come in for work (something that’s almost frowned upon in the fashion industry in London). It's normal to hike and swim in lakes every weekend, and spend weeks on end every summer in the countryside. There seems to be a more intrinsic respect and connection to nature through the time spent in it. If we want to feel that connection, we have to invest in time spent outside of the city.

In speaking to people all over the world about their lives existing at one with nature, what did you learn from them?

That really we are all alike. And there are remarkable people with the capacity to love and care for something outside of their own interests. That's the one thing they all had in common; a higher purpose to protect a planet so many of us are destroying. It's the easy choice to carry on as we are, watch the world burn and post about it in outrage on social media. It's a braver choice to really do something about it.

You have done a project previously called Reunion, photographing people reconnecting with natural space after the pandemic. But you're mostly known for your fashion work. How does your creative approach differ when approaching these two different subjects?

Honestly, there really isn't any difference other than time. With a personal project I can flesh out a concept and continually push it until it's fully evolved. That luxury isn't afforded with fashion work, where the deadlines are rigid and incredibly tight. But whether it's a commercial job, an editorial or a completely personal project, my process is largely the same. I am incredibly grateful and privileged to have achieved success as a photographer. Not many people manage to, and it is a job that has afforded me the time and funds to make so many personal projects that bring awareness to the key issues that drive me.

Do you ever feel that there's a collective sense of helplessness about the self-inflicted decline of our planet, and what do you think the power of imagery is in combating this?

Absolutely. I feel it often myself, and my only respite is to stand in nature. To work with it and be a part of it. Imagery should aim to inspire. Those saved images on Instagram shouldn't just be a moodboard. They should be a destination. I truly believe the more time spent in nature, the more we will fight to save it.

You've moved to the countryside – what do you hope to get from the experience of moving your life out of the city?

We have moved! Moving has afforded me a balance I was craving. I still love dressing up and coming into London to work and be amongst creative people. But, my energy comes from nature. I love going home at the end of the day to the quiet. I feel I can let out a long, held breath as I drive into the village. The cool breeze that wafts the smell of hay from the fields, the flutter of bat wings overhead, a beetle scurrying across the lane; light catching on her back. These daily occurrences bring you back into the rhythm of the natural world around you.

“It's the easy choice to carry on as we are, watch the world burn and post about it in outrage on social media. It's a braver choice to really do something about it.”

Daisy Walker

The book took you two years – what was the best place you visited and why?

I actually hardly traveled for the book. The plan was always to not travel anywhere for the book specifically. So, any journeys made were for work, and I would plan to shoot around the location I found myself in, so as to keep the environmental impact at an absolute minimum. The majority of the book was shot in and just outside London. The rest was done in Ireland, South Africa and Sweden. I would say the best place I visited was South Africa, and meeting Ozy who wrote a piece for the book. What I learnt about the interconnectivity between all living creatures is crucial to understanding our role as humans, and how close we are to our own demise.

What do you want people to feel when they read your book, and are you working on another one?

Love. Adoration. Wonder. A thirst to be in nature; to be at one with it. To respect these guardians and carers of our planet, and to want to be more like them.

I'm currently working on a smaller series of nudes, with proceeds going to Solace Women's Aid. To bring awareness and raise money for women experiencing domestic and sexual violence. As a survivor myself, I want to instill a sense of power and bodily agency in those who may be earlier on in their journey of coming to terms with the trauma they have experienced.