THE ORGANIZATION USING ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE TO UNLOCK COMMUNICATION WITH THE ANIMAL KINGDOM

WE SPEAK WITH JANE LAWTON, DIRECTOR OF IMPACT AT EARTH SPECIES PROJECT, ABOUT THEIR WORK DECODING THE LANGUAGE OF NATURE USING MACHINE LEARNING.

The idea of communicating with animals is a concept that’s long had a place in sci-fi and pop culture. Remember Darwin, the dolphin on 90s NBC show SeaQuest DSV, who spoke to the onboard naval crew using a ‘Vocorder’? Or Eddie Murphy’s turn as Dr Dolittle, a box office smash about a man who – quite unbelievably – learns that he can talk to animals as a child but forgets that he can until later on in life. We love to anthropomorphise animals in cartoons and films, because it’s a fantasy that we’re desperate to come true. Even though they’ve never said anything back, anyone with a pet will know you speak to them constantly. Like many things in the era of artificial intelligence, what was once confined to fictional stories is on the verge of becoming reality.

Earth Species Project is a non-profit organization using artificial intelligence to decode non-human communication. Inspired by the recent, rapid developments in machine learning and human language – such as ChatGPT being an established part of today’s world – Earth Species Project is seeking to unlock communication with the animal kingdom using those same tools. Far from being a distant, romantic dream cooked up by a sci-fi author, this technology is on the verge of translating animal sound and movement into a language we can begin to understand.

I spoke to the organization’s Director of Impact Jane Lawton to learn more about the Earth Species Project mission, how these advances in technology can be used to improve conservation and understand events like mass strandings, why this will never lead to a “Dr Dolittle moment”, and whether or not we could ever see a “voice of nature” on a sub council of the United Nations.

Jane Lawton

Q&A

I’m fascinated by the work that Earth Species Project is doing and I’d love to get a breakdown in layman's terms about the technology itself. Demystify it for me and Parley readers if you can.

What's really important to note is that we are not starting from scratch. The work that we're doing at Earth Species Project is inspired by the exponential advances that we have seen in human language processing over the last five to seven years. If we can start to translate across human languages using AI, how might this start to apply to what we are recording from the animal world? Everyone is now engaging with AI on a daily basis. We also now have the ability to translate across modalities, which is absolutely critical for animal communication. We are getting into a space with AI where everything that can be translated will be translated. This is really profound for animal communication because we know that animals – like us – are not just communicating through vocalizations, they're communicating through movement and chemical signals and vibrations, among many other mechanisms. In order to understand what is going on in their worldview, you have to understand the environmental context. It's incredible what we've seen in the last five to seven years, and we are building our models off all of those exponential advances in the human domain.

I know that you’re working on unlocking communication beluga whales. Could you tell me a little bit about that and also maybe how close that communication is?

There are a few organizations that are working on individual species, but we are actually species agnostic. We’re working on building machine learning models that can help to solve a lot of different tasks across a lot of different species. We think taking that approach and feeding lots of data in from lots of different species is going to help us get to breakthroughs faster. But this is a totally new field. We're moving from human language processing into a new field of animal language processing that has never existed before. We need to build models that are generalizable because we think they can have the greatest impact. As one example, we have this wonderful project with beluga whales. We’re working with a researcher called Jaclyn Aubin who works at the University of Windsor, looking at a population of beluga whales in the St. Lawrence River, a population that’s ranked as critically endangered. There are only about a thousand individuals left of this particular population of beluga whales. What's incredible is that they are so social – if you see the video of them coming together, it's just amazing to see the interactions. But the trouble is that they're all vocalizing at the same time, which you would think would be a really good problem to have because there’s great conversation happening that you could analyze. But the researchers were having to throw out 97% of their data because it was either too noisy or they couldn't separate the vocalizations sufficiently to analyze them.

At Earth Species Project, we've built a model for source separation that solves a longstanding problem in the animal communication field called the ‘cocktail party problem’. We've been working with Jaclyn to map the different vocalizations that she's recording from different individuals because the hypothesis is that although they seem to be one coherent population, there are likely subpopulations, potentially even slight differences in the way they communicate. We're not sure about that yet, but if we're able to analyze their communication and get a better sense of the social structure that is occurring within that population, then we’ll be able to design more effective conservation strategies. This is the whole purpose of Earth Species Project and why we do the work that we do, not just because it would be really cool to understand what animals are saying.

So you’re working to understand what animals are saying to improve conservation?

We're thinking about impact on a number of different levels. I've worked in conservation for a really long time and I think we have learned so much and we've made so much progress. But the problems are getting bigger – biodiversity loss continues to accelerate and that is incredibly concerning. Also, we're increasingly realizing how little we actually know and understand about what's going on around us. There are such great examples in the field of bioacoustics and communication about how nature is communicating around us every day and it's completely beyond our human perception because it's at the wrong frequency or because we just can't tap in, we just can't access it.

We feel like our work can have incredible impact on a number of different levels, including accelerating research workflows. If you think about the vast amounts of data that are now being gathered...there are these incredible new sensors that are gathering not just vocalizations, but movement data, environmental context, all of that kind of stuff. This incredibly rich picture could come out of it, but it's way too much data for human beings to analyze. So we are able to accelerate research workflows with really simple tools for detection and classification of signals in thousands of hours of recordings.

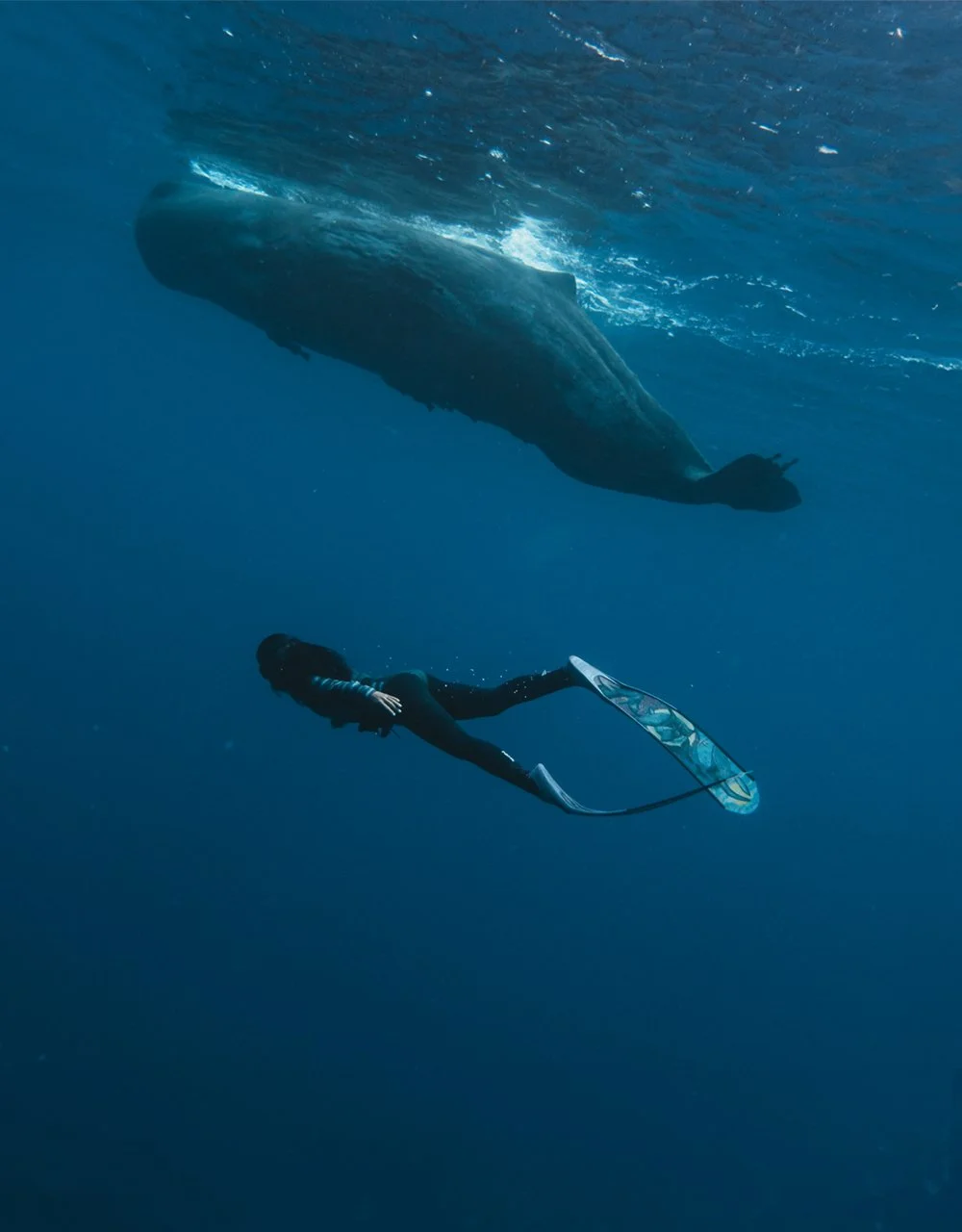

Moving up from that, as researchers are learning more about the species that they're studying, they are better able to design conservation interventions. In the marine space, if we were able to get a better sense of the meaning of cetacean vocalizations, would we be able to understand better why they have these mass stranding events? Would we be able to avert those? Are there ways for us to actually get into a space where we could avoid the number of ships strikes on whales, the leading cause of death?

Corals are in dire straits right now. One of the things that recent research has revealed is that coral larvae, far from just being pushed out onto the currents by their reefs and floating and landing where they land, they actually use sound to navigate toward a healthy reef. Could we use that ability to pull them to all the places where we need to restore coral? There's just so many myriad different ways to think about this.

We're probably in this situation of climate breakdown and biodiversity crisis because human beings ultimately have lost our connection to nature. We've forgotten that we're part of it. So can we use the new insights and breakthroughs that are coming through this work to try and reconnect people to nature? That can be done through just showing them, giving people examples, helping them understand the sophistication and complexity of the world of nature, of other species, the awe and wonder of it.

We also feel really strongly that our work can lend weight to a burgeoning movement in rights for nature. Are there ways we can actually start to bring the voice of nature into our decision making right now? A lot of that is being done through human representatives today. There's a few companies now that are actually putting the voice of nature on their boards of directors. Look forward 20 years, could we have a council for the oceans that is a sub council of the United Nations? It's all open to us.

“If we're able to analyze their communication and get a better sense of the social structure that is occurring within that population, then we’ll be able to design more effective conservation strategies.”

Jane Lawton

How close is communication with animals? What kind of insights are you getting, or what breakthroughs are you seeing?

I think it's really important to emphasize that this is unlikely to ever be a Dr Dolittle moment where we can just go out and have a conversation with a bird in your garden or a whale in the ocean. It's more likely that we are going to get a more sophisticated understanding of what other animals are communicating and that we may be able to map some areas of meaning. Because this is a new field we've really had to establish the benchmarks. How would we even know that our machine learning models are performing well? We can't tell what animals are saying, right? It's not like human language processing, where we know if they're doing a good job or not. We’ve established the benchmark data sets for vocalization and movement that will allow us to know moving forward, when anyone develops a machine learning model, how they are performing against a benchmark. Are we making progress? We are in a space where we're working with a number of research partners to refine those models and make sure that they are performing at least as well as, and in some cases, better than a human observer.

We're just beginning to get some real insights, in particular in a project where we're looking at carrion crows in Spain, which is a very exciting project. There's a subpopulation that's super interesting – they're cooperative breeders. So they actually raise their young in a creche-like situation, and different adults come in and out of the group to take care of them. So they have to communicate in more sophisticated ways to coordinate care of the young.

The research team has deployed really sophisticated sensors on these crows that are collecting all kinds of information. What we are working with them on is the ability to pair their movements and vocalizations to decode meaning.

I’d like to talk about any ethical concerns related to the work and the usage of artificial intelligence. It’s such a minefield and obviously in our human society it’s a big topic. It'd be good to get a reading on how you deal with that and how you think about it at Earth Species Project.

We are thinking a lot about the ethical considerations of this work and I would say they're actually pretty significant. We are basically eavesdropping on other species. Do they want us to do that? Do they want us to get to a stage where we are able to understand what they're saying? We don't know. The technology is moving really, really fast and it's pretty inevitable, given the exponential advances that we’re seeing, that we are going to be able to decode what's happening in animal communication relatively soon. So we need to make sure that with that new power, we fully embrace the responsibility that comes with that to make sure that as the tech develops, it is for the benefit of the species and it is to create positive change in the world.

There are real concerns that as we move into generative AI, where a machine learning model is actually able to generate novel vocalizations. In other words, it has then learned enough about how another species communicates that it can actually start to get into two-way conversation. In those cases, we might not even know what the meaning of that exchange is between the machine learning model and the animal. That could be really dangerous, particularly if it's in the hands of the wrong people. You could see how it could be used for hunting, or for poaching. It could be used to control animals in factory farm situations. We are thinking really carefully as we get into that space about how we make sure that access to our models is limited to those who want to use it in the right way. We're also thinking about the need for regulatory frameworks for this new suite of models. Much as governments around the world have sat up and taken notice of the potential risks of artificial and general intelligence, we feel like we could get ahead of this. We are thinking about how we can play a role in convening experts across a number of disciplines to start catalyzing that conversation.

That's a really interesting response – I didn't think about how it could be used for malevolent reasons, but I can totally see how it could be used for control or for poaching. Are you also conscious of a race against time? I know you're saying that the technology's evolving exponentially, but given that many animals are going extinct, does it feel urgent?

It does feel urgent. I think that most of the people reading this will have a pretty keen sense that we are not in a good situation with the climate crisis and the biodiversity crisis, so we do need to act quickly. Getting more information and a greater understanding of our fellow species is a critical ingredient in helping to drive new solutions. We also feel that it's important to basically get ahead of the technology, as I was saying, to make sure that as this develops, it is used responsibly, and in a way that can drive the greatest good in the world.

You mentioned carrion crows as a species where you're seeing exciting developments. What other species are you seeing real advances with?

We are doing work on orangutans and in that particular case the link back is to conservation directly. The researcher, Wendy Erb, is looking into the effects of smoke inhalation on orangutans, because they're exposed to a lot of smoke through forest fires that are burning continually in Indonesia and Malaysia. That can be tracked through analyzing their vocalizations and signs of stress in those vocalizations. There's some really great work being done on elephants with Joyce Pool who has been studying elephants for about 50 years in Kenya. That's all about mapping the structure of their communication and also understanding if they have unique names for each other. Some of the latest developments that have come out, not directly through our work with Joyce but through other teams, shows that they do have distinct names for each other and they will respond to a particular vocalization that corresponds to their name. It's fascinating.

This might be a silly question, but are you translating it into English? Or does it not work like that?

We are in some cases where it makes sense to do it. In the crow example, we are trying to understand the meaning of a particular set of signals. What we might find is something like a vocalization that means: “Aunt Rosa, it’s your turn to feed the chicks.” And in some cases, we might be able to translate it into something that is meaningful for us, but in other cases potentially not.

Let's say full communication with a blue whale was possible tomorrow and you could ask it one question, what would it be and why?

I've thought a lot about this and decided that I don't want to ask it anything. I want to be able to listen to what's going on in their world because as soon as I ask something, I am placing my human need and my human lens on what's going on with them and potentially interfering by introducing my ideas. I think we really need to pull back and say that this is about understanding and not necessarily about conversation.

OK let's flip it then. What do you think it might say to you?

I think it would likely say, ‘could you please switch off the boat noise?’ We don't even connect with the idea that our noise pollution is destroying the habitat and the ability for marine mammals to communicate – it makes their world impossible.

“Look forward 20 years, could we have a council for the oceans that is a sub council of the United Nations?”

Jane Lawton

Images courtesy of Earth Species, Ocean Image Bank, and Kogia