IN FOCUS: Victor Bezerra

Rio-based Ocean Uprise ambassador reflects on surviving childhood cancer and finding strength and belonging below the waves

I dive into my call with Victor Bezerra as one does in the digital age: with the click of a plastic mouse. A screen connected to an intercontinental web of underground and subsea internet cables casts my face from a desk in Maine, USA, to Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. I pull up my questions and flip to the page in my notebook where I’ve already underlined a favorite Victor quote, “the ocean doesn’t judge,” a truth he shared in an internship workshop with Ocean Uprise, a Parley initiative led by and for young activists. Victor appears in pixels, beaming, and the world feels a bit smaller for a moment — a fitting environment for a chat about how the oceans and photography remind us that we’re a part of something larger than we know.

After a childhood battle with brain cancer, and the formative trials of his treatment and recovery, Victor found a sense of belonging, wonder and purpose in the water. He felt home. Since acquiring fins and a snorkel mask, and experimenting with a waterproof disposable camera, the young activist has been captivated by the beauty of the ocean. In sharing it through photography, Victor hopes to inspire more compassion and empathy — for the oceans and humans.

Victor started documenting to prove to his grandmother that the ocean can be a safe place for a child to find independence and build confidence. That purpose evolved into a passion for underwater photography that is the anchor around which Victor now aspires to build a career in ocean conservation.

I first spoke to Victor while he was preparing to host his first open-air ocean photography exhibition, Tides of Hope, at Arpoador Beach, as the final part of his internship with Ocean Uprise (OU). We caught up again ahead of International Youth Day (August 12th) to discuss his new role as an OU Ambassador and where he hopes to go from here.

Q & A

You recently completed the Ocean Uprise internship program, where you held your first ocean photography exhibition, and have now become an OU ambassador to create change with the team. Can you tell me a bit about how you came to that opportunity?

The internship was a big thing for me, especially with the opportunity to host an open-air public photo exhibition. That made me feel empowered for the first time in a long time because it showed me that I was able to do that. I was capable of getting my photos and showing them to the world. And the feedback was nice. People who were just passing by wanted to learn more and get a deeper understanding of the exhibition. It made me realize that people are interested. When I shared my story with one family who were biking by with two kids, the father got very emotional. I felt like, okay, now I know what I'm capable of. I'm here. I'm showing my art to the world, thanks to the internship, and now I can do more.

When the opportunity to become an ambassador came along, I was like, okay, I'm ready for this next leap. It's a huge step. I have to reach 1500 people, but I'm ready for these challenges because I think after this, the world will grow for me as a whole — as an artist, as an activist, as a photographer.

What’s your goal for the ambassadorship? And where do you hope to go from here?

It's funny because it generates an internal crisis. After the internship and then the ambassador role, you get to a point where you're like, okay, now the world is bigger, the goal is way larger and it's more challenging. I sort of had an identity crisis. I am not a scientist, I'm an artist. And I love studying, but what should I do next? Should I study marine biology? Should I get a marine science degree? How can I be more impactful as an ocean activist, but still be a photographer? How can I become a conservation photographer? I think trying to figure all of this out is a huge part of being an ambassador, because things are never ‘pre-figured out’ for you. You figure things out along the way.

Now I have an opportunity, a larger grant to invest in myself, my career, my profession, and I want to use it wisely and impactfully? How can I find a way that allows me to invest in my art, but in a way that allows me to keep the impact going long after the ambassadorship has ended? I realized I want to gather technology and art in my project. I don't want it to be another beach cleanup. I want to involve people in the ocean. Since the beginning of my life project, the goal was, I want people to know the ocean.

"When I snorkeled for the first time, the whole world got better."

Victor Bezerra

You’ve said the ocean saved your life after surviving childhood brain cancer. You’ve had a difficult journey. How did you arrive at the discovery that the oceans could be healing, that they might make you feel better?

It’s a lifelong process, and thanks to a lot of therapy, I’ve got to the point of understanding what it has meant to me because yeah, I survived. In 1999, I went through surgeries to remove a tumor from my brain. It was a cancer called craniopharyngioma, which is actually a benign tumor, but it’s inside the brain, so it could kill me. The tumor was already big when we discovered it. It was February, right before Carnival here in Rio, and I was having headaches and double vision because the tumor was pressing on my optic nerves. I was complaining about it, but I was five. So everybody was like, oh, is he just joking? It's a cute thing. Then I crashed into a wall at school and my grandfather said, okay, something is different. He took me out of school and to the eye doctor, and he didn't find anything. I was complaining. I'm seeing double, I'm seeing double. He made me take a test. Everything happened so fast from the MRI after that.

They removed the tumor that February, but by August it had grown back. In the second surgery, they removed the whole gland. That's when my problems started, because besides recovering from brain cancer, I had no glands to produce my hormones. Now I’ll take hormones every single day for the rest of my life.

After the surgeries, I couldn't play soccer. Well, I could, but I didn't feel safe. The ball might hit my head or I could fall on the ground. Everything was scary, and I was overprotected. The kids weren’t nice at school. When I was in the ocean, I was just feeling like, okay, this place is safe. Gravity doesn't act on me here. I'm just floating and seeing a new world that nobody's seen. And I believe that that was the thing that made me feel so safe and at home, there in that place where things started fitting together. In the ocean, the pieces started gathering in, and I thought, okay, the puzzle is getting beautiful for the first time.

When did you find your love of snorkeling ?

When I was 10 years old, my grandparents started taking me to a coastal city close to Rio. They took me on a boat trip and offered me the snorkeling mask and fins. I tried it, and that changed my life. When I snorkeled for the first time, it was like the whole world got better for me, because now I understand that when you are floating and snorkeling, you simply find a world where gravity doesn't impact you.

I usually went snorkeling close to the rocks to find marine life, which made my grandparents nervous. Stay safe, it's dangerous! I was like, okay, no, I'm fine here. Nothing can beat me here. Nothing can happen to me in this place. I started finding starfish because this region has a lot of sea stars. The challenge became, instead of staying on the surface, to dive like two meters down, get the starfish and get back up to show my grandparents. Look at what I saw. I wanted to show them what I'm seeing, to say please don't be terrified, the world here is beautiful. And now I understand that that was when the ocean started to heal me. So every school vacation, they got me and took me to this place. And I started snorkeling.

When did photography enter the picture?

Maybe that first vacation, or the next. I found out that there were disposable film cameras that were waterproof… It was very funny because I couldn't see what I was shooting, and I wanted to shoot the starfishes. I wanted to register it all. That's where photography came together with snorkeling, because I wanted to show people what I was seeing, that wonderful world, because everybody else was there on the boat or just swimming at the surface, while I was trying to really explore that environment. When I carried a disposable camera, I wanted people to know what I was seeing in the water. The photos were awful, but the intention was good.

Victor's open-air photo exhibition

Victor pictured with his parents

"The ocean never judges."

Victor Bezerra

Do you have a favorite image of the oceans? Whether one of yours or another’s?

I consume so many images. I like studying, so I'm always looking. But there's one photographer who more recently has impacted my journey. Christina Mittermeier. I love her work, and I just completed her first online course, which is amazing because she brings her feminine vision to the world of photography. She tells this story on the course that while her husband, Paul Nicklen, is in the field taking photos of the bears and other wildlife, sometimes she couldn't go and explore with him, as she had to stay with the kids. So while staying in these villages, she started photographing people and culture. And she started to understand that culture was key to conservation, just like taking photos of the bear, the endangered species. I was mostly raised by women. My mother and my grandmother were key to my upbringing as a kid and as a person. I really appreciate how women see and do things.

What inspires you to keep documenting and sharing?

I have two sides in my head. I want to go and register what's there. But I also want to register what's dying, to show people what’s happening. I agree with the idea that when people see, they care. I've noticed the ocean and I have something in common. I survived. People see me as a regular person, but they judge me for being overweight, they can't understand, they don't want to understand, because they don't see my scar. They just see a regular person, they don’t see me and know my story. That happens to the ocean as well. So I think I have hope, because I am a proof of hope. I have suffered bullying, I have suffered from judgment, and I'm still here trying, working to show people what’s below the surface, that the ocean has so much to contribute, and to do that through images. When we raise awareness, we raise empathy as well.

How have your encounters with marine wildlife shaped you? Do you have a favorite species to photograph?

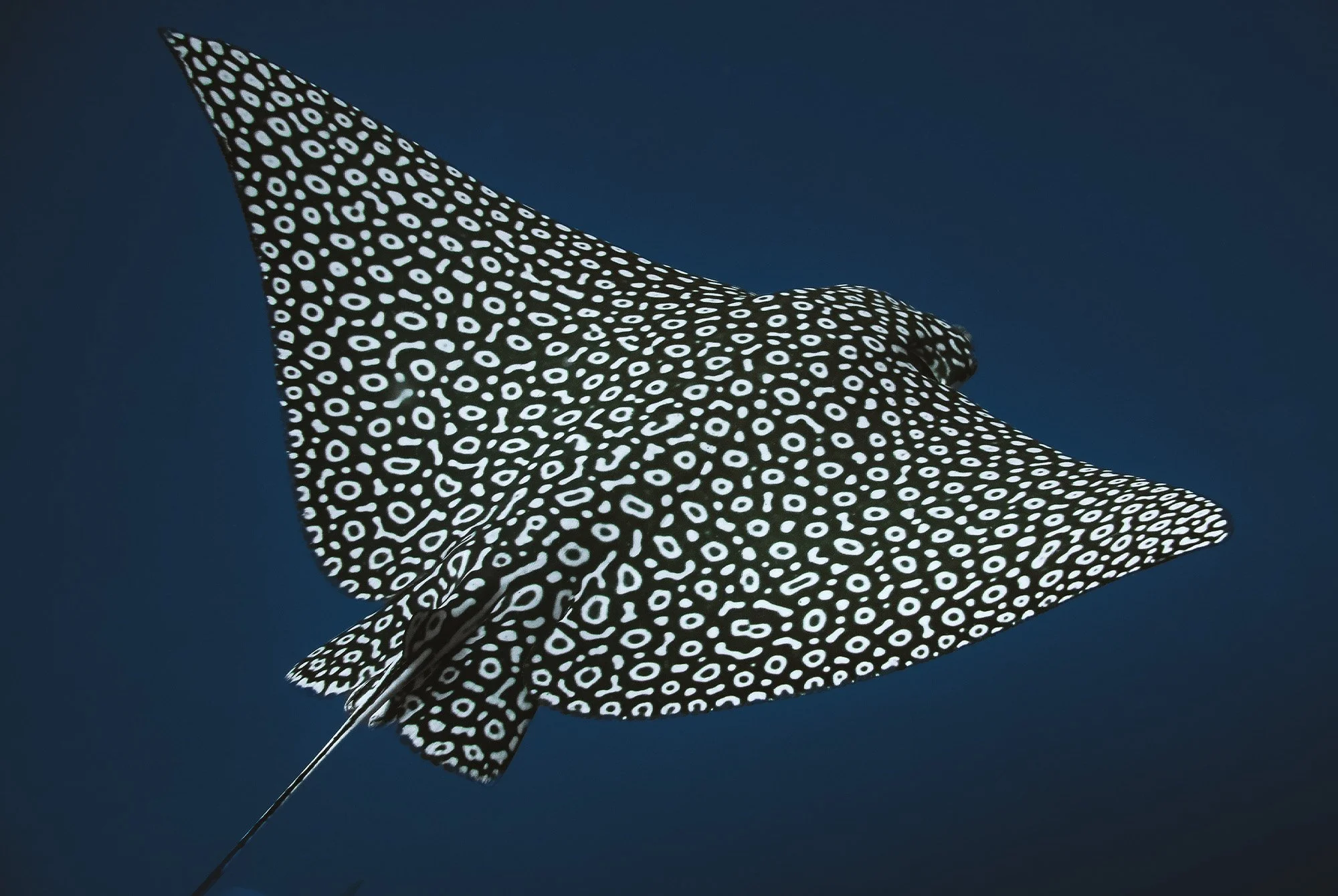

I love spotted eagle rays. They swim gracefully and the pattern on their skin is so beautiful. I feel a great connection with stingrays in general. I love photographing them. But the most special encounter was here in my backyard, snorkeling here in Rio. I found two spotted eagles at NAME OF BEACH, and it was like the most WOW moment in my whole life diving because you don't expect to find one in this place because it's very touristy. People are there every day, a lot of litter is left on the beach, on the sand, going into the water. So yeah, that was the most surprising.

And then during the pandemic, snorkeling was allowed, and there were fewer people at the beach, less trash. Animals could recover a little. I got to the beach one day and I saw a huge stain, a black stain on the water. Everybody was like, what's that? What's that? It moved and the surfers were paddling away from it. I got my fins and went to the water and it was a huge shoal of fish. It was crazy. I had never seen that before here and have never seen it again. So these were two remarkable moments where I was in the water taking photos, in a place where you swear you'll never find anything because there are a lot of people, there's a lot of trash, and even still marine life is resilient.

What’s the most important lesson you’ve learned from time in and around the oceans?

My biggest lesson is that the ocean never judges. When you are comfortable in the water, and not everybody is comfortable in the water, but for people who are, it doesn't matter whether you are fat, thin, black, white, tall or short, it doesn't matter if you're old or if you are young. If you really want to be in the water and to find out what's living, what's hiding beneath the surface, the ocean won’t judge, as long as you want to be there and you feel safe, because I think that's important. As long as you feel safe in the water and you want to discover, the ocean won't judge you. It just embraces you and allows you to find what's there.

Do you feel that some people are reluctant to step into environmental activism because of a fear of judgment, whether it's by people who don't really see themselves as doing enough, or others who might say that you're not doing it right?

I believe that we are never doing enough. We will always judge ourselves and believe we are not doing enough because we are really a drop of salt water in the ocean. It's hard depending on your personal environment, your friends, your family. You don't know whether other people like what you're doing, or you forget that there are other people doing the same thing. So, we often don't feel like we're doing enough because we don't know that we are actually part of a wave of people in the same movement who are trying to build the same future.

What motivates you to keep going?

Sometimes I dive at this beach where there's a small place that I call The Aquarium. It’s three rocks and together they shelter a lot of species, almost a nursery, and there are all these small fishes. I think that's the magic — you get to that place one day and you don't see a thing, because all the water is murky or the fishes aren't there, but you go back the next and you see all these different species inhabiting the same place, you think, okay, I'm trying to protect them. It's not every day that you're going to see the ocean protection you're trying to achieve, but when you do see it, it's more special than if you see it every day. Sometimes the world will be murky. Sometimes the world will be clear, and you'll get to see the impact that you're making.

What is your advice to people who want to get more involved in ocean photography?

Photography is a much more powerful tool than we think. And when we put our efforts into showing the world and using the cameras to show what we are seeing, part of my advice is not everything you see is as ordinary as you think. So, you can be snorkeling and you think, okay, everybody saw it, but not everybody will register or take that photo as you envisioned it. You can tell the story of that photo and that can lead people to change their minds and see the world as you saw through your photo, your lens. So use your photography as a means to change the world, at least your world.