Modern Synthesis is the biotechnology company creating fashion with bacteria

We visited the Modern Synthesis lab in London to get a firsthand look at the products that they’re making using K.rhaeticus bacteria and learn more about their journey into the fashion industry

At Parley, we’re always thinking about the future. What can the world look like? How can it be improved? How can we not just live in harmony with nature, but learn from it? We are aware that we cannot simply recycle our way out of the plastic crisis – we need to redesign the structures and systems that pollute our planet, along with the harmful materials that we’ve become addicted to. It’s why we’re calling for a Material Revolution – we have to change the way we make things in order to create the future. This new Parley series will meet the innovators and scientists who are trying to remodel our material world.

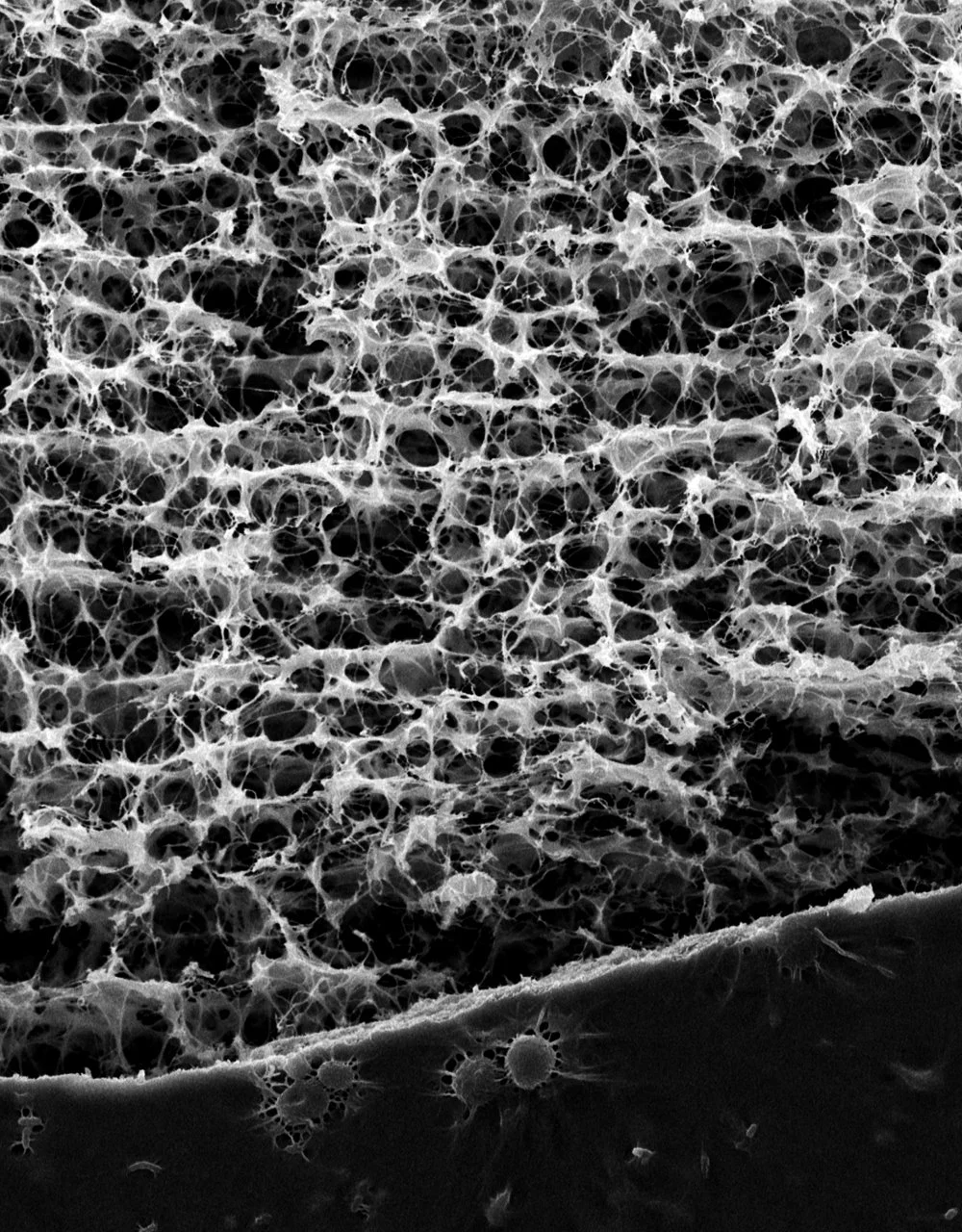

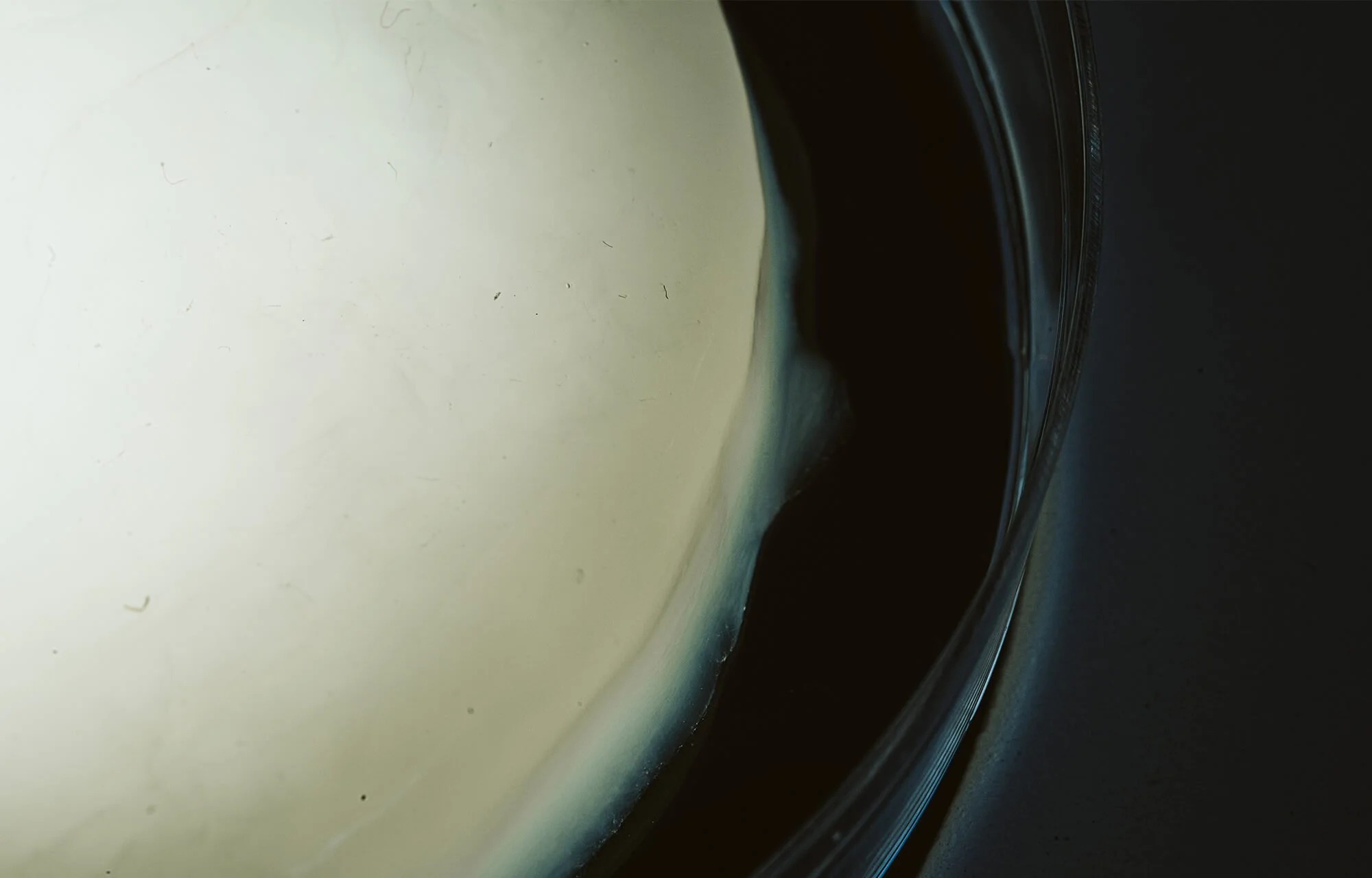

In an unassuming laboratory on an industrial estate in South West London is a shoe that’s been grown from bacteria. The unique footwear is the work of Modern Synthesis cofounder Jen Keane. The shoe is the result of a project called This is Grown that was inspired by the plastic crisis, completed during her masters degree in Material Futures at the prestigious fashion and design university Central Saint Martins. By manipulating the growing process of a bacteria called K.rhaeticus (which is found in kombucha tea), Keane developed a form of ‘microbial weaving’. This new way of approaching material design is organism-led, a technique that collaborates with the origins of life on Earth in order to help design its future. As it’s fed sugars and it grows, the K.rhaeticus bacteria leaves nanocellulose trailing behind it to form a fiber, which can be modified to an exact shape using robotics. At the fiber scale, nanocellulose fibers are eight times stronger than steel which gives them an inherent durability. The result is an incredibly lightweight, strong, naturally biodegradable raw material that can be used to create new textiles that displace plastic films or leathers.

At the London Design Festival in September 2023, Modern Synthesis unveiled its collaboration with Danish fashion brand GANNI. They revealed a first-of-its-kind version of the brand’s iconic Bou Bag – only this time it hadn’t been made with leather but bacterial nanocellulose. The process that Modern Synthesis has developed could generate significant reductions in greenhouse gas emissions, while still looking and feeling like cowhide. Now, plans are afoot to make a 100% biofabricated Bou Bag commercially available by 2025 and work is underway to remove the plastic microfibers that are currently used on the lining of the prototype. It’s incredibly impressive work and we’re lucky to have been invited into the Modern Synthesis lab to find out more about Keane’s journey, the fast-growing company that she founded with Ben Reeve, and what makes nanocellulose such a valuable material.

Cofounders Dr. Ben Reeve and Jen Keane

Nanocellulose structure under microscope

Q&A

How does nature inform the work that you do and how important is it that we learn from ancient systems in order to create our future?

Nature is the ultimate circular economy and we have a lot to learn from the organisms that were here many years before us. Bacteria and fungi were the original life forms on the planet, and they're very good at converting what's around them into what they need to survive. I think we can reflect a little bit on how we interact with the materials and all of the resources around us. Production has become a very linear process – taking things from the earth, converting it into what we need and not really thinking about how that goes back into the earth. I think by looking at how these other natural systems have evolved, we can take cues on how maybe we can design better systems in the future.

The company was founded during a project created in response to the plastic crisis. How confident are you that we'll be able to totally phase out single-use plastic, and how long do you think that will take?

It's a very complex problem. The challenge is that plastic is a useful material. You can do a lot with it, and that's why we've so quickly as a species adopted it into many different areas of life. A lot of the life that we live today is enabled by plastics, like forms of transport and whatnot. I think it will take time to phase out, and where we need to focus is on all the areas that plastic doesn't need to be, first and foremost. For example, packaging and fashion – you don't need your clothes to last for thousands of years. We only live on the planet for a small fraction of that, so why should the clothes we wear outlast us?

Within textiles and fashion, there is a big movement right now to move away (from plastic) and it will take time to convert those supply chains. I think we're looking at a few decades to 50 years for that phase-out to happen, because there's so much already being created. What can speed that up is governments taking action to actually drive this change, incentivizing companies to make those switches quicker, supporting new technologies like ours, looking at things like cellulose-based materials, alternative proteins, and figuring out how we can achieve the same results with regards to the products that we need and use every day, but with a very different material system.

What do you love about working with nanocellulose as a material, and what's exciting about it?

What's most exciting for me is the adaptability of it. Everyone has talked about graphene for a long time and I would put nanocellulose in the same bucket, in that you can mix it together with other things. You can create the structure and you can really make a wide variety of different materials with the same technology. It’s similar to why plastics have been so good – that versatility and the ability to use it in different ways. It’s the same with nanocellulose, which means that we can tackle a lot of different problems head-on.

The other thing that's exciting about it is the circularity potential of it. Bacteria converts sugar into nanocellulose and it can use any type of sugar. It's feedstock agnostic, which means as the bioeconomy evolves we can have different sources of raw material inputs and adapt to a constantly changing environment. At the end of life, it's cellulosic, so there's a lot of work going into cellulose recycling streams at the moment to make other yarns like lysol, but also there's work going into bio-recycling. You could break that material down in the future, back into sugars, to feed back into that system and create a closed loop. Nanocellulose gives a lot of flexibility for both application adaptability and end of life.

Beyond GANNI, has the fashion industry as a whole been receptive to what you're doing?

The fashion industry knows that it needs to change and there are a lot of good people who are working every day to find ways to lower the impact overall of the products that they're making. We've had a lot of interest from brands that want to work with us, and are excited by the potential to create new design possibilities with this new material, not just as a lower impact alternative that does the same things as current materials.

The brands that we spend most of our time with are those that see the potential of these materials to change fashion and the products that they're designing. There's an opportunity creatively to be like, "What can I do differently with this? How could I design a bag differently?” That's both a challenge and an opportunity for us.

“I'm a designer by background, but I also dabbled in the sciences and I quickly learned that you can't make change without all of these different disciplines working together.”

Jen Keane — Cofounder, Modern Synthesis

What are the main challenges that you face?

I do think there is a way of working that the fashion industry has been used to, that needs to change. I think a lot of designers don't really understand the materials that they're using, they're used to going to a fair or supplier and just pulling something off the shelf. There's an education that needs to happen around the sustainability of those materials, but also how you approach design, keeping those factors in mind. I think that's something that people are aware of, but needs to be pushed a lot more within the fashion industry as a whole.

The other big challenge for companies like us and startups, is that the funding models weren't designed for what we do. If you think about textiles as an industry, most of these companies have evolved over decades, not hundreds of years. There has been a lot of innovation in the last 100 to 200 years, but that was privately funded and it was funded very slowly. We're trying to make big changes in a very, very short timeline, and so we need access to capital that both understands that and is set up for making physical things. The funding models were originally set up for software. You can't apply the same funding model for software as you can making physical goods. Unfortunately, people get stuck in this cycle of, "Oh. It doesn't fit our model." Well, let's redesign the model!

How does cross-disciplinary collaboration manifest itself in the work that you do at Modern Synthesis, and why do you think it's so important?

I'm a designer by background, but I also dabbled in the sciences and I quickly learned that you can't make change without all of these different disciplines working together. Design on its own isn't going to solve all of our problems. We need to engineer new machines, we need to build factories. We need to look fundamentally at biology, chemistry, and without conversation between all of those parts we can't get there. It's so important that these disciplines are put in a situation where they can collaborate and have these conversations, but also come with that mindset and respect for the other disciplines so that we can get there together.

How can we arrest the disconnect that exists between human and nature currently?

The disconnect between humans and the rest of nature is one of the biggest challenges of our era and it's very deeply entrenched. We are nature and somehow we've forgotten that. How do we tackle that? Manufacturing has been increasingly outsourced over the last 100 years and I think that's contributed a lot to a disconnect, in that we don't know how most of the products that we use every day are made. We're not involved in that and it doesn't affect us individually. A move back to local sourcing, a hands-on connection with the goods that we have, will help drive that a little bit more. The sad part is that as climate change progresses, I think everyone's going to start becoming a lot more aware of how that impacts on each and every one of us and our day-to-day lives as they are today and a decade from now.

You worked at adidas for several years – how did that experience in a large corporate environment shape what you're doing today?

Working for adidas helped me understand how things are made at a global scale, how big that system is and how much we actually make. Adidas is an incredible company – they're well-structured, they have an incredibly well-ordered supply chain, they've got good relationships with their suppliers. They care about the wellness of the people that make their products and they're one of the first companies that was really looking at sustainability, even though they weren't talking about it.

I learned a lot from their approach but I also think there's a realism that was really driven into me from my time there of it being great to have ideas about how we could work with biology to design all these wonderful things. But also, there's a reality of the supply chain that we have and we have to make sure that we marry the now with these future visions. Otherwise, we'll never get there.

“Nature is the ultimate circular economy and we have a lot to learn from the organisms that were here many years before us.”

Jen Keane — Cofounder, Modern Synthesis

Nanocellulose Pellicle

You are part of that wave of innovators who are redesigning the material world, which to me feels like a huge, exciting responsibility. Does it feel exciting and does it feel like it's moving fast?

It never moves fast enough, it is very exciting. I don't know what else I would be doing now and I do think it's great that this movement is happening because I think for a long time the fashion industry was very static, so I'm excited that change is happening. I think that there's a lot of pressure on innovators to make this change, but I think brands and supply chain partners are starting to realize that we can't do it on our own. I'm hoping that they're realizing that a bit more and that we can work more closely together to really embed these new technologies within the existing system, because otherwise it's difficult. I feel like sometimes it's easy for big companies to say, "You sort out all my problems, and then we'll talk." But we're a fraction of the size! I tell brands all the time, "Tell me what you need, tell me what we're doing well and what we're not doing well, because we exist to help you." We won't be able to do that if we're not honest with each other.

Imagery courtesy of Modern Synthesis