NUVI: Creating the Future of Textiles that Return To The Earth

We speak to the Frankfurt-based company about their past, the ABSURDITY of the present, and their pioneering new fabric made from flowers

At Parley, we’re always thinking about the future. What can the world look like? How can it be improved? How can we not just live in harmony with nature, but learn from it? We are aware that we cannot simply recycle our way out of the plastic crisis – we need to redesign the structures and systems that pollute our planet, along with the harmful materials that we’ve become addicted to. It’s why we’re calling for a Material Revolution – we have to change the way we make things in order to create the future. This new Parley series will meet the innovators and scientists who are trying to remodel our material world.

Today, NUVI’s forward-thinking material experiments and design take place in a small room in Frankfurt, but the origin story begins nearly 9,000km away in Thailand, over a decade ago. While living in Southeast Asia, NUVI founder Nina Rössler began experimenting with teak leaves picked from the forest floor in Chiang Mai, attempting to figure out how to transform the plants – plentiful in the region – into a sustainable leather alternative. Nina was a keen yogi and an initial ambition of hers was to create planet-positive accessories for people to practice with. In fact, ahimsa, the ancient principle of non-violence that’s fundamental to yoga, remains foundational to NUVI’s work today. After successfully creating products such as wallets and yoga mat bags using teak leaves, Nina and her partner Christophe Cappon realised that they needed to head to Germany in order to scale their vision for what NUVI could become, bringing Nina’s father Andreas onboard, an engineering expert. NUVI officially launched in 2014.

Tragically, Nina passed away in 2022, but Christophe and Andreas have continued to carry out the vision that she set for the company, determined to honour her legacy and her mission to leave the best kind of impact on the planet – none at all. As of now, NUVI creates textile materials in Germany that are made exclusively from local plants and minerals. “Marmora” is a coating made from marble, “Creta” is a material made from champagne chalk, and their newest is “Papilio”, that they describe as a “pioneering biomaterial” made from butterfly pea flowers. In fact, when I reach Andreas and Christophe on the phone, Andreas arrives slightly late, stressed as he’s frantically been trying to ship samples of the new material to the Future Fabrics Expo in New York, where people will lay eyes on it for the very first time. The duo are extremely excited about “Papilio” as they believe that it embodies everything that they’ve been working towards and that there is no other material like it in the world, a translucent coating that honours the natural beauty of the flower, keeping the color and smell, without trying to emulate a material that already exists.

Christophe is in a philosophical but optimistic mood as we wait for Andreas to join, reflecting on how it can sometimes feel like nothing’s happening fast enough, but enjoying a renewed sense of purpose having recently gone through the NUVI archives. “It’s easy to feel like it’s going nowhere,” he says. “And yet, looking back through our archives it turns out that we’ve actually achieved a lot in a short space of time. It’s a very modern thing – to feel like you’re not doing enough, or things aren’t happening fast enough, with the pace of the world now.”

We caught up with Christophe and Andreas to talk about NUVI’s past and its future, drawing inspiration from nature, and their own personal journeys that led them to inventing biomaterials.

Co-Founders Andreas and Christophe

“50 years from now, we'll look back and be like, what were we doing? That was a crazy time. Of course things should biodegrade and not harm the planet, because we’re harming ourselves, right?”

Christophe Cappon — Cofounder, NUVI

Q&A

In simple terms, can you explain the problem that NUVI’s work is addressing?

Andreas: It started when my daughter, Nina, was in Thailand. She was looking for material that she could use for making handbags, belts, yoga mats, or some alternatives to leather – synthetic or real. In Thailand, she found a material made from teak leaves but the material was more like paper, it didn’t have the capability to take stress like leather. She started working on it because she saw that there was not much available at that point in time and, if there was, it was plastic. She got into her kitchen and started cooking up some recipes, just experimenting. Eventually, she came up with a basic recipe of the product that we have today, just using things that she had in her kitchen.

You talk about your materials being created using regionally available plants and minerals. Can you go into more detail about them? What makes them special to create textiles with, and is it important to you to be using things local to you?

Andreas: Sure. It’s important to use local products because firstly we look at the design and ensure that we have something that feels and smells attractive. Secondly, we want it to be sustainable. So we localize, something that also makes our material attractive.

What specific plants and minerals are you kind of working with?

Andreas: We’re currently working with chalk and marble. We’ve also used slate and basalt, just to name some. We also did trials with tobacco leaves and at some point later tobacco powder. We were also conducting trials with powder from wine or grape leaves.

Do you have a favorite material, plant or mineral to work with?

Andreas: My personal favourite is still tobacco, but that’s because I like leather. I really like bovine leather, the way it behaves and smells. With tobacco, the material is very close to a natural, undyed type of leather. I'm also fascinated by our papillo at the moment because that is something that has transparency and natural colors in there. If you look at products, they typically have colors. For example, if you look at a whiskey and the color it has, it's something different, it's not something you can find in a product. If you look at a tea, it has transparency, it has life in it. And this happens with our material. We can encapsulate this idea, the transparency of the tea, and keep it in our material. You can see that when you look at it – that is the very fascinating thing about the new products we are making.

Your name stands for a fearless embrace of tomorrow's possibilities, and I'm very excited by this space that you guys are in. And how excited are you both about the future of biomaterials and also the work being done generally in the biofabrication space?

Andreas: It's mandatory. We have to, everybody has to. I'm an engineer… I look at the past when people started with plastic materials in the 1930s or a little bit earlier. The material that was produced at that time is something that we find in nature today as microplastics. It took since the 1930s to disintegrate to microplastic, and what we see today as microplastic is that old. Now, imagine that there for 70, 80, 90 years we keep increasing the amount of plastics and dumping it into the world. It won’t be what we see right now. It will become more and more and more, and we have to stop that.

How long do you think it will take for us to move away from plastics?

Andreas: It will take some time. We want to compete with plastics and we need to be able to compete with plastic materials because everybody is so used to it that you can't do without it at the moment. With our material, we have a chance to replace maybe not all plastics in the world, but some of it. Our material is biodegradable so within a year, if you put it into the right conditions, it's gone.

I was speaking to another designer recently who made the point that we make millions of products that last four or five times longer than a human being does. Do you think that we should all be making things now with biodegradability built in?

Andreas: Yes, I absolutely agree with that. At the very least it should be one of the properties that you look at when you are choosing a material. If you're building a house, you want to have a material that lasts for a long, long time, because houses need to last for a long time. But if you are making a handbag or a wallet, people are not used to passing wallets onto their children. It has to decompose, to leave the planet without any damage.

I'm interested in both your personal journeys and what led you to work in this field. Andreas, I know that your daughter co-founded the company and that you came on board, but I just wondered how long you’ve both been conscious of the climate and the impact that human infrastructure and economies are having on the planet.

Andreas: For me, as an engineer, it was always a dream one day to not leave any footprint on this world. My idea was always to generate the energy that I consume by myself using solar energy. Now, I have the chance to do something that’s helping us to reduce the footprint that we leave on this earth. It’s a basic motivation for me.

Christophe: The whole NUVI thing was very unexpected and totally left field for me! Not to mention one of the most challenging things I've ever done, but also one of the most rewarding. I've lived most of my adult life in Southeast Asia, where I am confronted on a daily basis with the reality of plastic pollution, air pollution, everything pollution! In the West, we live in little bubbles, and we have no clue what the majority of the human population is dealing with. Plastic pollution here has always driven me crazy. NUVI was the opportunity for me to be the change I want to see in the world, so to speak. I've also, in my past life, been very much involved with yoga and its industry.

One of the tenets of yoga is non-harming and NUVI is very much philosophically aligned with that. Who’d have thought that a yoga teacher from Thailand would end up leading a sustainable biotech material company based out of Germany. I just stepped up to the plate when I was called to action. I didn't seek this, it came to me. After all, Nina was Andreas's daughter and my girlfriend – we met in a yoga class in northern Thailand. Before we knew it, we had created the first generation of material in our kitchen out of teak leaves. Ten years later we’re still drawing inspiration from those roots.

Eventually we shifted everything to Germany as that’s where Andreas, and the brands, are based. We wanted to source, produce and distribute in Europe as that's where our market was. We didn't want to do continental shipping, which feels completely backwards. Then, in the midst of the covid era, Nina got cancer. So Andreas and I stepped in further so she could focus on her recovery. For several years we managed to keep it going, the torch alive, in the hopes that Nina would come back to it, but she didn't. At least not in physical form.

We were three – Nina was the interior designer, Andreas the engineer and me the yoga guy - and now we're two. However we're still heavily influenced by the vision that she laid out. In the beginning I was doing it for her. Then for Andreas, and now finally I'm doing it for myself. And to some degree, for the world, the planet and for the better of humanity. I do believe that it's only because of those deep, intense bonds that we have with one another that we were able to overcome so much for so long. If it was just to make some money and save the world… I don't think it would've been enough. It’s the love for our little founding family, I think, that keeps us going.

“It's only because of the deep, intense bonds that we have with one another that we were able to overcome so much for so long. If it was just to make some money and save the world… I don't think it would've been enough.”

Christophe Cappon — Cofounder, NUVI

We talk a lot about “nature being the best designer”. What inspiration do you guys take from nature when it comes to NUVI's work?

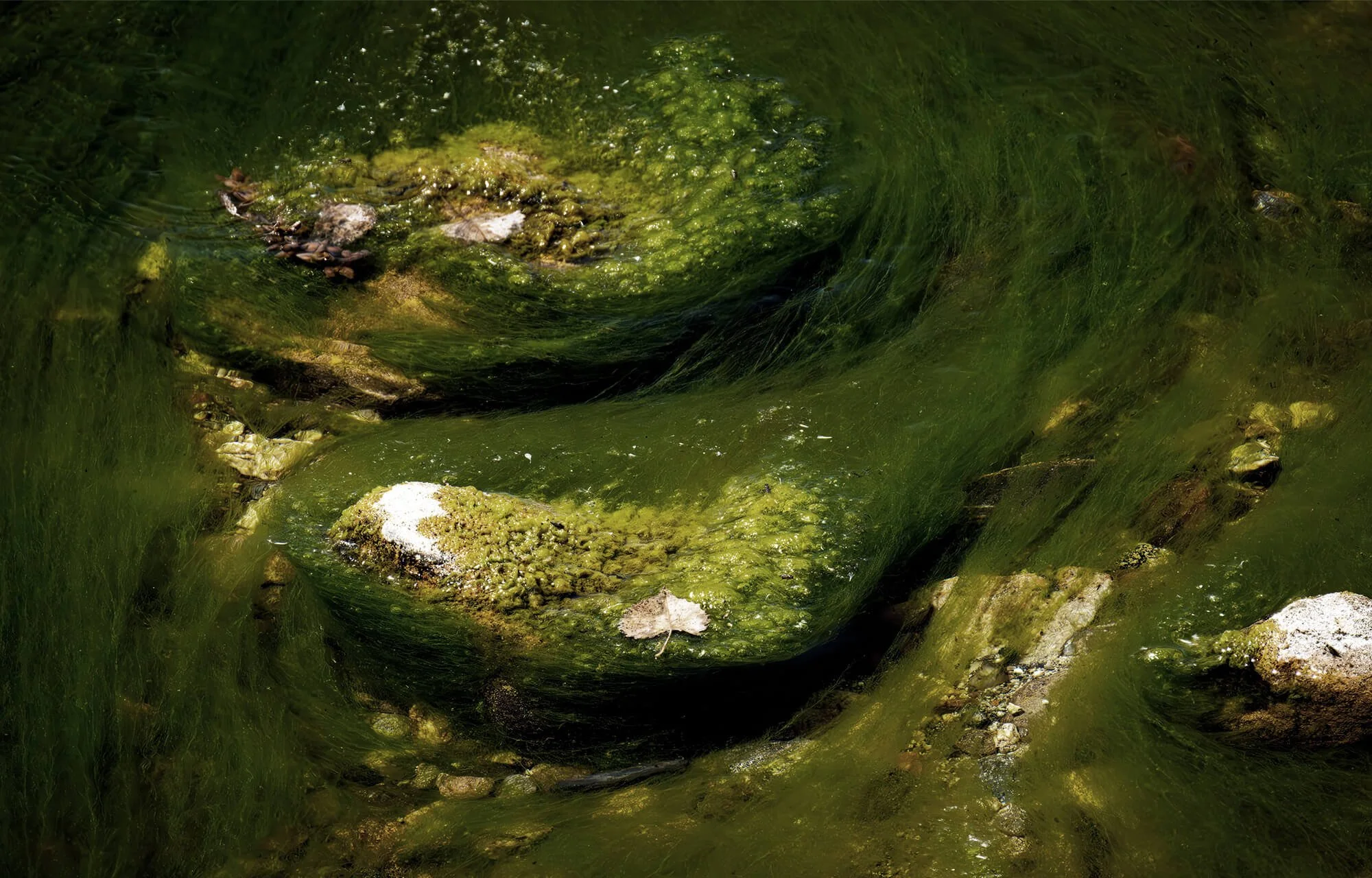

Christophe: I would say our favorite design is no design. The less we mess with it, the better, which is why we're working so hard to do that. But simplicity is actually the hardest thing to achieve, right? At the moment, our material has just a handful of ingredients, which in itself is rather incredible. We're trying not to add color, we're trying to retain the smell, even the texture, the whole emotional feel of the main ingredients. Not just the way something looks, but all the sensory experience of when you're confronted with a flower, for example. Not to mention the associations you have with that flower and the memories that it triggers. That's what we're trying to tap into.

Andreas: Yes, it is nature that builds our brain and our views, which I love to work with as an inspiration. It's much more natural than creating things that are not from this earth, which for me is not satisfying. I always remember the moment from the Stanley Kubrick movie 2001: A Space Odyssey. You have this moment where you see the earth, the apes or ancient humans, and then all of a sudden there's this black slab which does not belong to the earth, it’s something that does not belong here, it's from somewhere else. Many engineers try to make something that is not from this planet. Yes, there is some fascination there but at the end of the day, it's not coming from us. It's not part of us and with it not being part of us, I don't care about it. If it's done by you, by people, if you can see that it's living, that it's our material, that it's decomposing, it becomes part of you.

Christophe, you mentioned yoga earlier. I'm interested in the yogic practice ahimsa and how that informs the work that NUVI does.

Christophe: Ahimsa is a Sanskrit word – the translation is essentially “non-violence”. It's one of the tenets of yoga and should guide our action toward all living beings. It's not about being vegan, it's about doing good for the planet, but in a way that's not boring. We’re all about making cool shit, and always have been. Earlier, you asked me where I think sustainability will be in the future. Well… I don't even think it'll be a thing. It won't even be a word, it'll just be standard. What we've been doing is just completely ludicrous anyway. We're doing everything wrong, everything backwards. 50 years from now, we'll look back and be like, ‘what were we doing? That was a crazy time‘. Of course things should biodegrade and not harm the planet, because we’re harming ourselves, right? Of course, as human beings, we like pretty things. And what better inspiration than nature?

What do you perceive the ultimate use cases for NUVI being? And how do you envision your work scaling? What are the challenges you face with that?

Andreas: We have to find the applications that fit our material as it is right now. Then, the next step is improving our materials for more applications, for more use cases. At the beginning, it will be like the textile world – replacing synthetic leathers, replacing the need to kill cows and other animals just to get a natural leather material. But with more development I see a chance that we can come up with other replacements for plastics. That would be a spinoff and a major change.

Imagery courtesy of Sandra Weller, Christian Huller, and Daniel van Hauten.