Tavake Pakomio: Science at sea

Conducting science way out on the open ocean comes with its own set of challenges. Parley coordinator Tavake Pakomio takes us through her experience of sampling plastic in the South Pacific.

Information and knowledge are power. A well informed community is more willing to protect what they know and care about — a key pillar on what the team of women on the eXXpedition sailing program set out to accomplish through their research. Over the course of three years, 300 women will immerse theirselves in hands on, scientific research to understand the “natural” travel trajectory of plastic once it enters the ocean, all across the world.

The two-year mission will in part help to advance a better understanding of the plastic epidemic as a whole and to pinpoint solutions and policy at global level by addressing knowledge-gaps and delivering evidence to inform effective solutions. Tavake Pacomio, our Parley representative on Rapa Nui, joined Leg 8 of the expedition, sailing from her native Easter Island to Tahiti. Here, she introduces to us to some of the techniques used aboard.

“Science in a boat sounds simple, but physically it is very demanding… the gym was not needed!”

Tavake Pakomio

Over the course of the three weeks the team spent traversing the Pacific, they used two main scientific techniques for sampling:

Manta Trawl

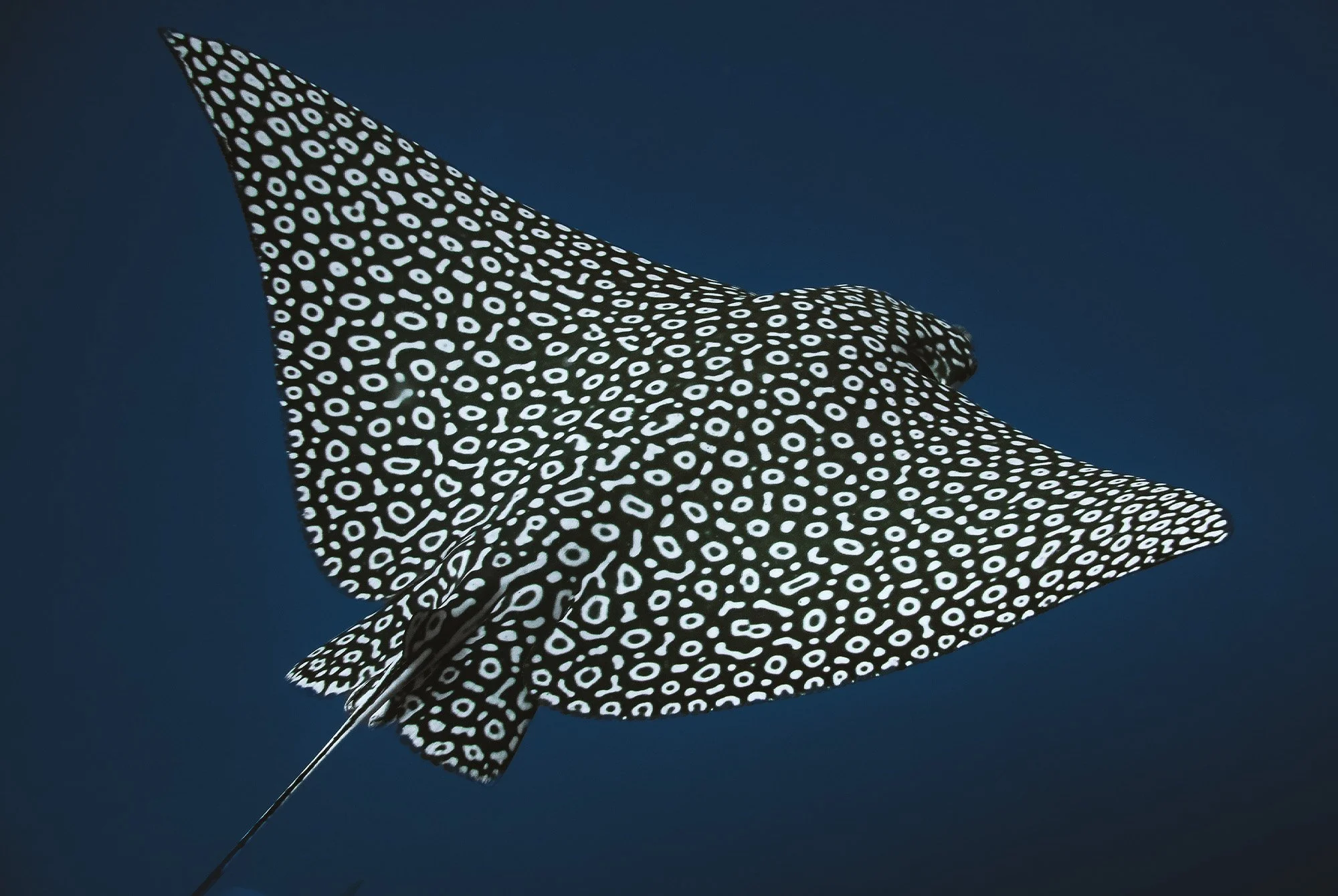

Made from aluminum and fine mesh netting, this floating device hangs from a rope that is hooked to a lateral pole attached to our main mast. It looks a bit like a manta ray with a wide open ‘mouth’ – and like real mantas it sadly accumulates plastic, even in the middle of the South Pacific.

To collect samples, the Manta Trawl is lowered overboard and towed alongside the boat to capture any floating plastic on the ocean surface while filtering debris through the mesh net.

We do this on a daily basis and it requires 5 or 6 people each time the Manta is suspended, because of its heavy weight. The device trawls on the water's surface for 30 minutes to capture a large surface area of the water. While the device is being towed the crew mates record other information including coordinates, time, weather and ship speed. Once the samples are collected, the plastic particles are filtered through different sized strainers and stored in small glass bottles.

Niskin Bottle

This device is used to collect subsurface samples, specifically in waters 25 meters below the ocean surface. A Niskin Bottle is a plastic cylinder with stoppers at each end in order to seal the bottle completely. This device is used to sample water at a desired depth without the danger of mixing with water from other depths. Subsurface sampling is undertaken to study the composition and distribution of different plastic polymer types within the upper ocean, which is currently a data deficient topic.

On the ship, we would toss the bottle that was connected to a rope into the water for a few minutes to collect water. Once the bottle was filled we would bring the nearly 10kg structure back to the boat's surface, which would require three to four people. The Niskin was then manually pumped and passed through a paper filter. Any inorganic material (plastic) that was left was then stored and labeled in a petri dish for documentation.

Tavake reflects on the team’s findings

The motion of the ocean lends itself to be very complex and variable, meaning, the distributions of plastics vary over time and space. Each leg of the eXXpedition concludes different results and calculations, therefore, continued studies are needed to examine temporal and spatial patterns of the ocean and how that affects the flow of plastic particles.

“We found just a few pieces of plastic in our mission to the South Pacific ocean, very small ones,” says Tavake. “This took my attention because in Rapa Nui our coast is very polluted from industrial fishing materials and you expect to see them spread around but we didn't see any box, buoy or net.”

In 2018, eXXpedition conducted another mission to the North Pacific and the amount, size and variety of plastic they found was overall way larger than what Tavake and crew found. They concluded that the North Pacific Gyre collects a larger mass of plastic because the majority of the world’s population lives in the Northern Hemisphere, therefore, this area has more activity, traffic and waste.

“I realize how islands play a very important role in this situation, acting like a net to attract, by the ocean movement, and catch plastic,” explains Tavake. “It is a sad reality knowing that everyday 8 million tons of plastic is thrown in the ocean, with a large portion of it ending up on coastlines, especially island nations. Our work on land to manage this waste is key. Educating about the problem, creating awareness and putting more value in our territory to protect the land.”

Solutions need to come from everywhere. There is no single solution, no magic solution, no single person or government that will fix this. The challenge is expansive, contaminants are found in the most desolate of places. We must utilize a diverse, collaborative network to combat this burden that is slowly suffocating our oceans.