In Focus: Rick Miskiv

We catch up With Rick Miskiv, whose relatively recent underwater photography journey has taken him to capture incredible images in Palau, Baja, Tahiti, Belize and beyond

Based out of San Diego, Rick Miskiv is a long-time Parley collaborator who has graciously shared many beautiful underwater images and videos with us over the years – from the incredible jellyfish lake in Palau to sharks in French Polynesia our recent post about marlins and sea lions hunting together in Baja. Sharing our deep love of the ocean and a genuine desire to inspire change, we want to thank Rick not just for sharing his time and work with us, but countless other NGOs pursuing similar goals – including The Hydrous, Oceans 360, The Ocean Agency and MarAlliance

With a background in fine arts and tech, Rick is passionate about helping ocean organizations communicate the cause to a broader audience. Over the course of his career, he has lived in Japan, Malaysia, Thailand and Palau – the latter to work in the dive industry as a dive master and instructor. Notable past projects include working with Asner Labs and the Carnegie Institution for Science on an expedition to document a coral survey of the WW2 wrecks of Bikini Atoll in 3D Virtual Reality. As one of the featured photographers in the Coral Reef Image Bank, he has contributed photographs for free use in coral conservation efforts.

In addition to photography and filmmaking, Rick founded his own ocean gear brand, 22 Degrees while living and working in Palau. Working in a similar way to Parley, he set out to create a range of ocean apparel with eco-innovation baked in – using recycled polyester and shipping supplies, eco-friendly carbon black and limestone neoprene. We caught up with Rick recently as he prepared for a series of freedives with humpback whales in Tahiti, desperate to not sound too jealous.

“There’s a minimalist beauty to photographing sharks against the open blue, those gradients of light that feel like being inside a James Turrell installation.”

Rick Miskiv

Q & A

How did you first get into photography and ocean photography? Was it two separate things?

Photography and my connection to the ocean developed in parallel for years before they merged. I have a BFA and MFA in fine arts, and photography has been a constant throughline in my creative output – whether as a finished product, a tool for research or visual journaling. I think visually, so the camera feels like a natural extension of my creative process. I’d been doing photography since high school, first with a Canon AE-1, shooting my friends skateboarding and abstract patterns on walls and asphalt. But it wasn’t until I worked as a dive master in Palau that I saw underwater photographers in action and realized the potential for visual storytelling beneath the surface. I had a desire to learn to capture these unique experiences in a compelling way.

It took a few more years before I had access to proper housing and equipment, but when I finally started photographing underwater for ocean conservation work, everything clicked. The two streams of my life – visual thinking and love for the ocean – finally merged into something that felt both creatively fulfilling and purposeful.

What’s your earliest ocean memory?

My earliest memory of the ocean is being maybe six or seven at Atlantic City, begging my parents to take me down in this old diving bell exhibit on Steel Pier. Pressing my face against the glass, searching for life in that murky green water… even though I couldn’t see much, the experience was exhilarating. Looking back, there's a clear thread from that childhood curiosity about what lives beneath the surface to eventually having the tools and skills to actually show people what's down there.

Where are your favourite places to work and what are your favourite ocean creatures to capture?

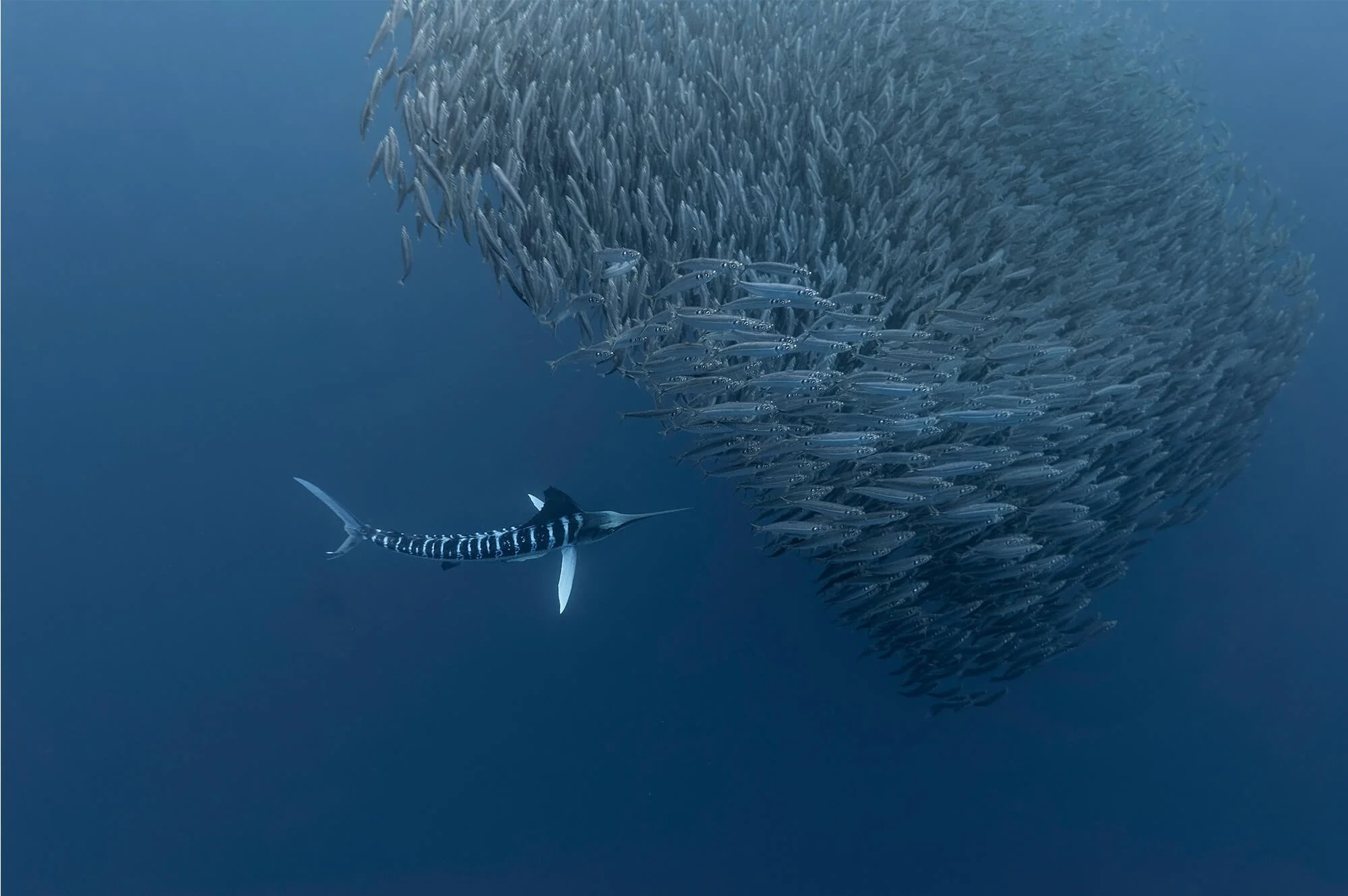

I’m drawn to the most dynamic environments (cleaning stations, strong currents and the open blue) and the creatures that thrive in those spaces: sharks, mantas and marlins working baitballs. Mantas at cleaning stations fascinate me because they embody this beautiful systems thinking – the reef as one organism, these intricate webs of interdependence and symbiotic mutualism. I’ve been fortunate to photograph reef mantas in Palau and oceanic mantas off the Socorro Islands. There’s something about the soft flow and sensitivity of a manta, their curiosity and gentleness, and the depth you see in their gaze. They move through the water like living meditation.

We’re big fans of your shark and marlin work too.

Sharks represent this perfect evolutionary form – intensity and grace as they drift in currents. Whether it’s oceanic silvertips in the Bahamas, Caribbean reef sharks in Honduras or grey reef sharks in French Polynesia, they’re apex predators that maintain balance in their respective ecosystems. There’s a minimalist beauty to photographing them against the open blue, those gradients of light that feel like being inside a James Turrell installation.

And marlins working baitballs in Baja? That’s pure kinetic energy. The dance, the power, the speed. The way the baitballs move and shift, creating these dynamic shapes through emergent behavior from simple rules. It’s like witnessing the ocean’s choreography unfold in real time. What connects all of these for me is that they’re windows into different ways of experiencing the world – each creature’s unique umwelt, their sensory reality that’s so different from ours. That’s what I’m trying to capture and share.

“The ocean teaches us about cycles, resilience and finding new equilibrium.”

Rick Miskiv

What changes have you seen in the oceans since you got started?

When I first started getting serious about diving about 15 years ago, I wasn’t aware of all the pressures on reefs, oceans, and climate. I’d heard from older divers about changes since the 90s, and in time I began experiencing locations with degradation and coral bleaching – some of which I witnessed in real time.

There was a shift in me as I became aware of what we could lose and how fragile this ecosystem is that I’d previously seen as immense and unchangeable. Teaching new divers, I watched them experience awe at their first encounters, and I realized we all suffer from shifting baselines – each generation normalizes what they first see as ‘normal.’ It’s part of why documentation through photo and video feels so important – creating a record of what came before. When I attended my first Parley conference in NYC, I felt enormous optimism from all the participants and the UN presentations. It felt like the world was listening. Since then, the urgency has only intensified, but global attention seems focused on other struggles.

But here’s what I’ve learned: these struggles aren’t separate from ocean health – they’re all interconnected. The ocean teaches us about cycles, resilience and finding new equilibrium. My role as a visual storyteller becomes even more crucial when attention is elsewhere. Every time I witness those transcendent moments underwater — when everything connects and you feel truly alive — I’m reminded that awe is still there, waiting. That’s what I’m searching for now, and what I want to help others find for themselves.

You must have experienced so many amazing moments underwater, is there one or two that really stand out?

There are so many, but a few moments in Baja really jump out. The whole ecosystem there – baitballs, mobulas, sea lions, marlins, dolphin pods against that rugged, undeveloped coastline – has this sense of raw, unspoiled nature that’s increasingly rare.

I once found myself separated from the other divers, alone with this massive baitball and a large group of sea lions taking turns hunting. They were dancing through the water with incredible agility, splitting the school of fish, and I was right in the middle of it all. I was photographing, but had to pause and just put the camera by my side and take in the moment. For a brief time, I wasn’t just observing it, I was part of this spectacular dance happening in every direction around me. It was pure connection to something larger, and a feeling of humility.

Another time, a school of bonitos attacked a baitball until the water was literally boiling with frenzy. Fish scales were descending like snow, and it was all happening directly in front of me. Pure energy. Those are the moments I’m always searching for — when the boundary between observer and participant dissolves completely. When you feel truly alive and connected to the ocean in a way that’s impossible to fully capture or explain.

“Change in living systems doesn’t come from a single command center; it comes from individual actions at scale, simple behaviors that influence larger outcomes.”

Rick Miskiv

How has VR changed the way you can communicate ocean moments like this?

I did work with VR for a few years, particularly on projects documenting Palau, Bikini Atoll and Honduras – stories that felt important to tell through that immersive medium. The projects were about awareness and using VR to immerse people in the wonders of the ocean who might not otherwise experience them, whether they didn’t scuba dive or weren’t close to an ocean. At the time, there was a lot of excitement about VR’s potential for creating empathy and connection, the idea that putting someone virtually underwater could create a deeper understanding of these environments. The best thing about VR was witnessing the excitement and joy of schoolchildren engaging with the content in the goggles; laughing and excited. Children really got the most out of the medium and were least judgmental of its limitations. It sparked their imaginations. I remember showing the Palau footage to Palauan school children who grew up on the islands but had never experienced the reef underwater. They took great pride in its beauty reflected back to them. While VR was compelling and novel, it never really fulfilled its promise in terms of accessibility and reach. The technology just didn’t gain the widespread adoption we’d hoped for.

What I’m focused on now is more direct collaboration with scientists and researchers. My most recent project was with CNN and Mar Alliance in Belize, documenting their work tagging sharks and loggerhead turtles. This kind of visual storytelling feels more immediate and impactful — taking scientific data and research and making it accessible to broader audiences.

Scientists speak in data, but photographs and video can expand their reach and help people understand the importance of their conservation work. Whether it’s showing the process of tagging a shark or capturing the moment a turtle is released back into the wild, these images help tell the story behind the research in ways that data alone can’t. That collaboration between science and visual storytelling feels like where I can make the most meaningful contribution.

Beyond working on meaningful projects like this, what gives you the most hope for the future of our oceans?

It’s easy to feel overwhelmed right now – the news is full of setbacks for conservation and climate solutions. But what gives me hope is shifting my perspective from top-down to bottom-up thinking. In nature, I’ve witnessed how emergent behavior creates something larger than its parts: those baitballs in Baja moving through simple rules to create complex, dynamic forms. Change in living systems doesn’t come from a single command center; it comes from individual actions at scale, simple behaviors that influence larger outcomes.

That’s where I find optimism now — at the community and individual level. Every scientist I collaborate with, every person who sees an image and feels that spark of connection to the ocean, every child laughing in a VR headset seeing the reef for the first time – these are individual nodes in a larger network of change. My role as a visual storyteller is to create those connection points, to help people experience that sense of awe and wonder I feel underwater when everything dissolves and you’re part of something larger. Because once you feel that connection, that humility and aliveness, it’s harder to turn away.

The moments that stay with me aren’t just about capturing beauty. They’re about bearing witness and inviting others into that witness. It’s still worth the effort to try, to not slip into nihilism or apathy. That’s what keeps me searching — for awe, for connection, for those moments that remind us we’re part of an interconnected living system, not separate from it.