Intercepting & Upcycling Ghost Gear in Mexico

One year into an ambitious interception and upcycling initiative funded by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, we visit the Parley team in Mexico working to make the seas safer for marine life and coastal communities

It’s mid-morning, the sun is beating down and we’re hovering high above the seabed in a small boat, waiting for a replacement part to be brought out to us. The mechanical breakdown has given us the chance to peer down into the crystalline waters north of Cancun, which are so clear we can see right down to the sandy bottom, deep below. It feels like we’re floating in the air above a desert, but with the occasional sea turtle passing beneath us. The pure, aquamarine clarity is deceptive though – our teams know only too well how much plastic debris is hiding in the oceans.

Ghost gear (fishing nets and other equipment that has been abandoned, lost or otherwise discarded) is the deadliest type of debris for marine animals and has the potential for the greatest negative economic impacts on coastal communities. At least 800,000 tons of it ends up in the oceans annually – although the actual amount is likely far higher. Since fishing nets are purposefully designed to catch and kill marine animals by being as durable and difficult to detect underwater as possible, the ecological destruction from ghost nets is compounded over time. Monofilament gill nets are usually made from nylon, an extremely durable plastic that doesn’t break down, is nearly invisible in the water, is easily lost and is inexpensive to re-purchase: a disastrous combination.

Once they enter the environment, fishing nets – particularly monofilament gillnets – indiscriminately continue catching marine animals. Nets can end up as ghost gear due to a combination of factors, including bad weather like hurricanes and storms, the quality and the age of the fishing gear used and losses during fishing activities. Once lost, the nets can become embedded in reefs, seagrass, mangroves and other sensitive habitats – making it very hard to retrieve.

“Mangroves are one of the main ecosystems that is being affected in significant ways by this type of waste,” explains project lead and Parley Mexico coordinator Alejandro Rodríguez. “There is where we typically find entangled monofilament as well as nylon mesh – and mangroves are always the hardest environment to work in. Inside the mangroves we find not only nylon, but refrigerators, televisions, really large pieces of debris at the heart of these forests. But it is hard to get really deep into the mangrove.”

With repairs soon complete, we’re back on our way to Isla Contoy – a low-lying island featuring beaches where sea turtles nest, a sheltered lagoon where frigate bird soaring overhead and thick, fringing mangroves. As the boat pulls in to drop us off, we see exactly what Alejandro means. Climbing down into the mangrove forest, the team faces a choice between thick, stinking mud or a precarious climb through the branches trying to stay above the waterline. Add in some mosquitoes and the increasingly fierce midday sun and you begin to appreciate the challenges of working in these remote areas.

Contoy is just one island where Parley Mexico is now working as part of a huge new program to intercept and upcycle ghost gear in the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico. Funded by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Parley’s Mexico AIR Marine Debris Mitigation Initiative is collecting derelict fishing gear from 16 fishing communities in the States of Tamaulipas, Veracruz, Campeche and Yucatán in the Gulf of Mexico and Quintana Roo in the Mexican Caribbean. Working with CONANP (the National Commission for Natural Protected Areas of Mexico), the vast project stretches across 17 Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) along 4,470 km of coastline, and aims to provide a local end-to-end solution for monofilament nylon nets by upcycling them locally. Cleanups and local education projects will also form a key part of the initiative, with a focus on coastal communities, university students and fishers.

The goals of the initiative include

Collecting fishing gear and preventing it from being discarded in the environment

Upcycling monofilament nylon nets

Directly engaging with fishers in the region

Intercepting marine debris from the coastline and sensitive habitats on Mexico’s Gulf coastline and off Quintana Roo in 118 cleanups

Engaging volunteers in the debris removal

Educating and engaging people in six states in Mexico directly in talks

Protecting the biodiversity Gulf of Mexico ecosystems and endangered wildlife by preventing ghost gear and removing the marine debris

The artisanal fishing fleets in the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea commonly use nylon monofilament gill nets, cast nets and nylon monofilament longlines. This fleet has grown over 500% in Mexico over 30 years, with the primary fisheries being shrimp, shark and various seasonal fisheries. Studies and specific information regarding numbers of nets used in the region annually and the rate of loss or amount discarded into the environment is lacking, but a study of abandoned, lost or otherwise discarded fishing gear in the Caribbean reported that the majority was underwater (60.1%) with the remainder on shorelines (24.6%) or floating at sea (15.3%).

Mexico recently made significant progress designing and decreeing new laws for the management of solid waste – with waste from fisheries (including supplies used for fishing) being of special concern and management, which in theory means they should be delivered to entities capable of recycling and upcycling them. On the ground, the reality is that waste nylon from fishing nets and lines is commercialized in regional informal markets. Fishers resell even their most beat-up nets and gear to poorer members of the community for a good price, and purchase yet more virgin plastic nets. This helps to keep some nets from being deliberately dumped, but contributes to an ongoing cycle of degradation and loss – with broken down nets eventually ending up in the environment in various forms.

“Local fishers know that plastic nets still have an economic value,” explains Kim Ley Cooper, coordinator of the fishing gear component of the project. “Most are not deliberately leaving that waste in nature. They are not dumping it and leaving – they are selling the waste. The main use for waste nylon is to keep on constructing nets for illegal fishers for the poorest of the artisanal fishers. For guys really not having funds or economic power for buying new nets, they are buying refurbished nets and that's the main use. They also use them for animal pens on land, and other projects.”

Despite the high local fishing effort, the biggest challenge the team has faced so far is not finding enough nets inside the Marine Protected Areas themselves – something Kim attributes both to good management and to the price of the nets themselves at the informal market of waste nylon. “The nets we are now intercepting in the MPAs are really lost fishing gear – with nylon in pretty bad shape and with the lowest quality possible. It’s really toasted and is already degraded by the sunlight.”

The commercialization of nylon waste in informal markets represents a collective loss. On one hand, the price of waste nylon in these markets is up to 60% higher than its price in the formal international marketplace. On the other hand, when good quality waste nylon is sold, its decomposition into microplastics is allowed to continue and in the end, those who acquired it will burn it in the open air or throw it away like any other solid waste. This prevented waste nylon from being handled and processed properly and from contributing to the regional and national economy by using it in products of greater utility and value. It is a net loss for the circular economy.

“The protected areas we are working in are really housing incredible biodiversity – manatees, sea turtles, crocodiles, mammals, birds…”

— Kim Ley Cooper, Parley Mexico

Converting nylon waste into usable plastic will be the next big challenge, with upcycling infrastructure due to arrive and be constructed in Cancun later this year. Once operational, the team will work closely with fishers and coastal communities to recover and upcycle as much nylon as possible. The upcycling station is a modular container that will transform the monofilament nylon nets back into raw material. The equipment consists of a shredder, grinder, multi-step washing and drying process and water filtration, to ensure all contaminants are removed. No chemicals are used – a simple eco-friendly detergent is sufficient for the washing process.

After the nets are transformed, they can be turned into 3D printing filament or used in any number of product applications. This creates an unparalleled opportunity to create an economically self-sustaining circular economy initiative beyond the initial 24 months of the project, and will allow it to be scaled. Since nylon can be used in a variety of products and the quality of the pellets will be high enough that the pellets can be used for 3D printing filament, eyewear or other consumer or industrial applications, there are nearly limitless product applications. Given enough recovered nets, Parley Mexico’s upcycling equipment could process 300 metric tons (660,000 pounds) of plastic annually.

For now, Kim, Alejandro and the team continue to intercept and store ghost gear and marine plastic debris for processing – a job that regularly takes them to some of the region’s most beautiful and biodiverse places. As we leave Isla Contoy after cleaning a beach with some local students, Kim reflects on the remote places like this the project is helping to protect.

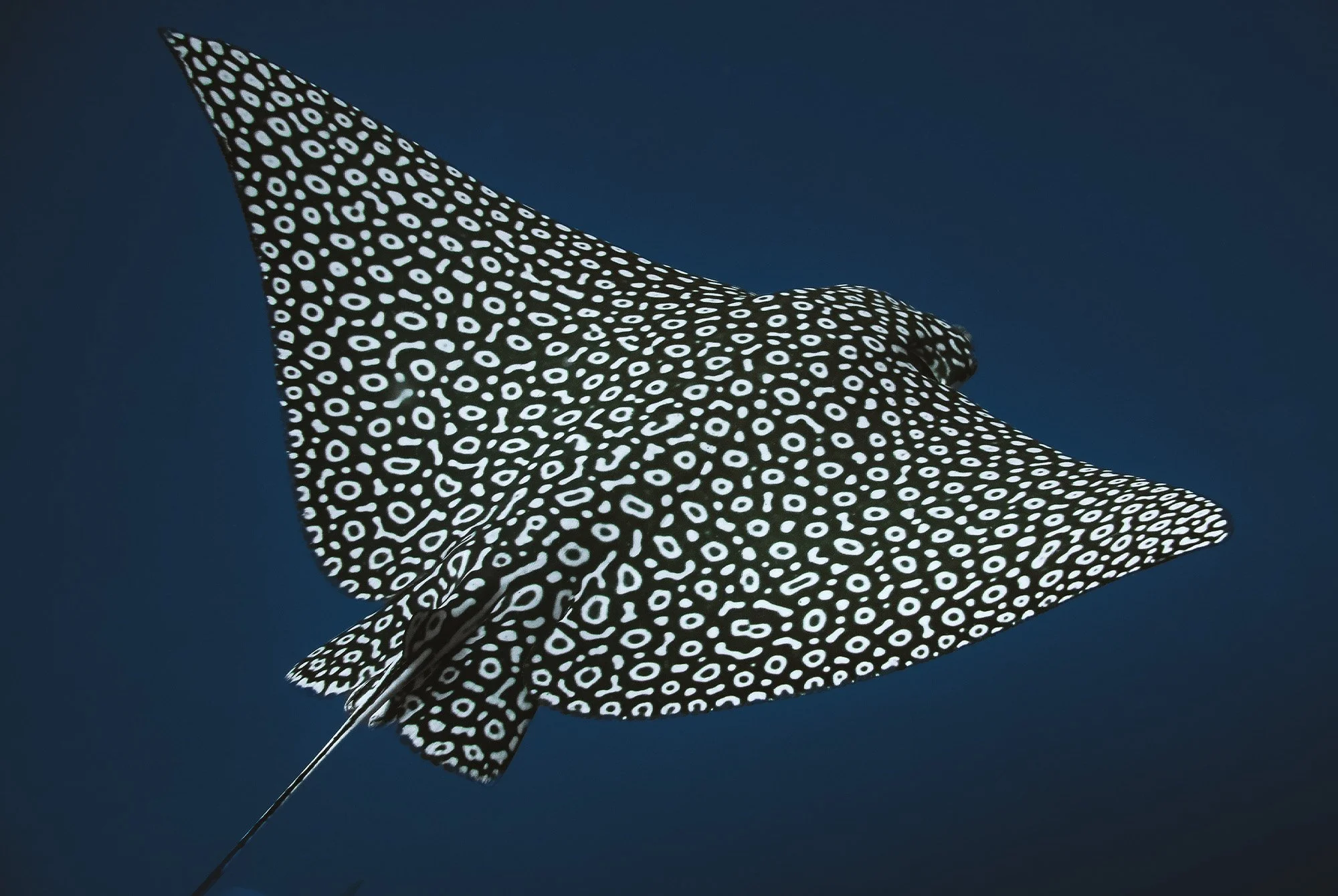

”The marine protected areas we are working in are really housing incredible biodiversity,” Kim explains. “We have manatees, sea turtles, crocodiles – we even have mammals that are hunting – or that used to hunt – in mangroves. They're interacting with this waste in negative ways, so removing it is the first step. All these MPAs we're working in are also incredibly important for migratory birds too, and we’re also seeing plastic impacting on them.”

Photography by Ami Sioux & Naiara Altuna