A Wilderness Beneath the Waves

IN THE FIRST OF A THREE-PART SERIES, PHOTOGRAPHER AND FREEDIVER AVERY SCHUYLER NUNN TAKES US INTO THE HEART OF A KELP FOREST AND EXPLAINS HER PERSONAL CONNECTION WITH THESE HIDDEN ECOSYSTEMS

If someone asked you to picture “the wilderness" what would come to mind? Perhaps a jagged mountain range, blanketed in snow, topped with wispy clouds. Maybe at the base of those craggy peaks, there’s a freshwater lake that reflects the sierra above, as an eagle soars overhead. That’s what I used to envision, and the mountains and forests still stir something deep in me. But arguably the most overlooked, least protected and most exploited wildernesses are the ones that don’t initially come to mind at all: our oceans. Perhaps that’s precisely why they remain that way.

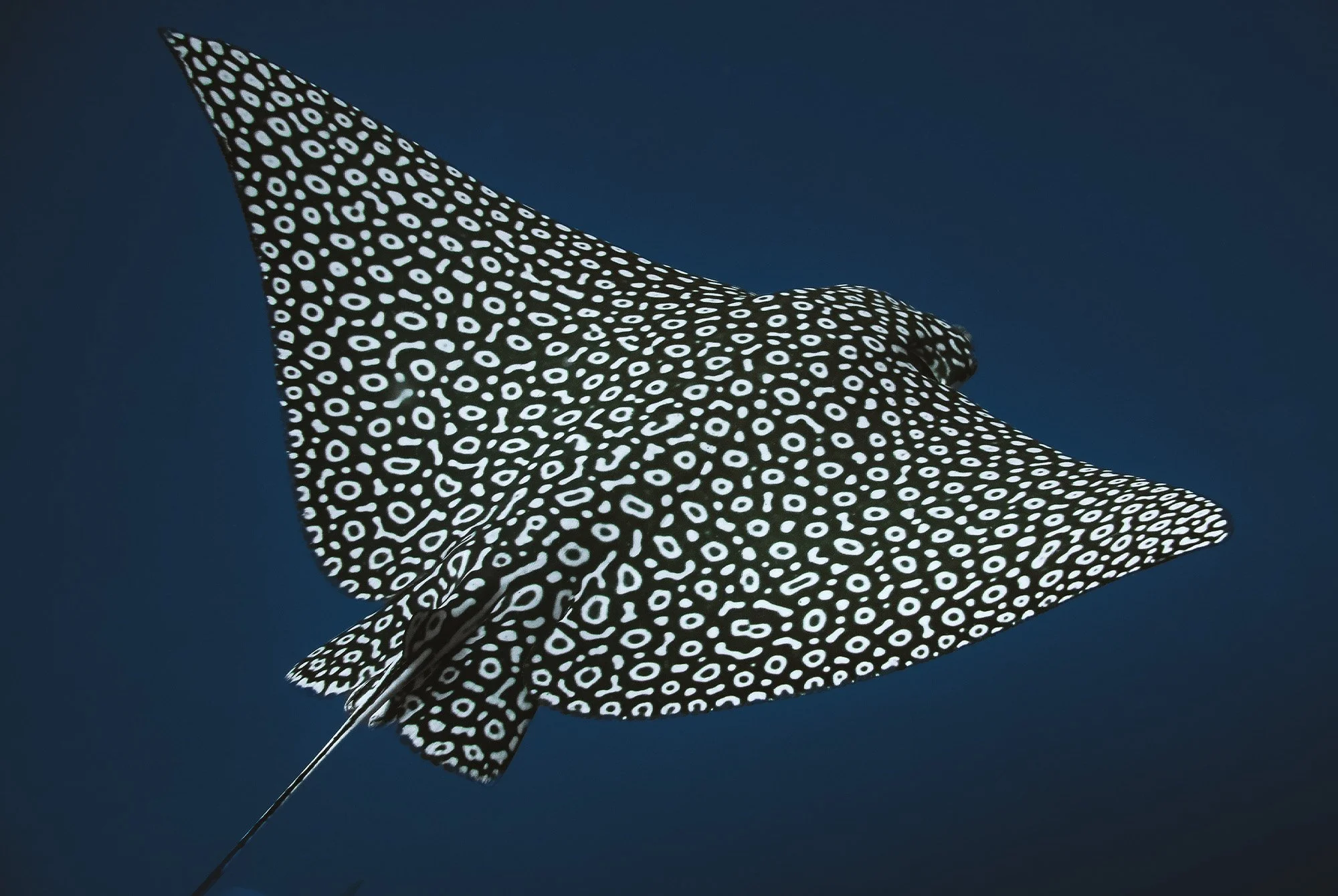

From the shore, a kelp forest looks like just a few bulbous fronds floating at the surface – but beneath those glimmers of gold lies an entire universe: a living, breathing ecosystem of essential wildlife. Schools of fish dart between the swaying fronds. Seals weave through sunbeams and nap in the rocks along the seafloor. Rays glide across meadows of seagrass. Sea otters wrap themselves in the floating kelp canopy, munching on sea urchins or cradling their pups in the safety of the fronds.

“arguably the most overlooked, least protected and most exploited wildernesses are the ones that don’t initially come to mind at all: our oceans.”

Avery Schuyler Nunn

When I was a child growing up on the East Coast of the US, there were two places that fostered my earliest connection with the outdoors and my insatiable zest for exploration: the forest and the ocean. I remember bounding barefoot along moss-lined trails, my arms spread wide to mimic the birds whose song carried down from the trees above. I’d look up to feast my eyes on the golden sunlight as it oozed through a canopy of beech, maple, oak and sycamore leaves. The sponge-like release of damp earth beneath my toes, the scent of fallen leaves and pines, and the joy of searching for frogs along the creekside.

In tandem with my foundational and endless love for the woods was an ever-increasing infatuation with the ocean. Along the coast of southern New Jersey, I spent my summers playing in the waves, opening my eyes beneath the surface to watch how the light bent and rippled as the swells passed overhead. I felt the salt on my skin, watched for horseshoe crabs and piping plovers along the shoreline, and searched for critters in the nooks and crannies of the jetties – long arms of rock that reach out into the ocean.

In 2021 I moved out to California, where I found a sanctuary that merged the two elemental oases of my upbringing: a forest in the ocean. After my first submersion in a kelp forest, I was captivated. I would go on to spend the next three years freediving nearly every day – chronicling the shifts beneath the surface, learning the language of the tides and the species that call it home, and falling in love with this underwater haven.

We call them kelp forests, but what we should really call them are kelp jungles. In marine protected areas, these golden cathedrals are wild in a way that few places still are. As both a journalist and a freediver, I’ve watched once-lush stretches of kelp turn to urchin barrens within a single season. Kelp forests are vulnerable to a cascade of threats: warming oceans, overgrazing from urchin population booms, the collapse of key predators like sunflower sea stars and otters, and pollution that clouds the water and smothers new growth.

Across the globe, kelp forests stretch from the cold, nutrient-rich waters of South Africa to Norway, from Chile’s rugged coast to Australia’s Great Southern Reef, from the Pacific Northwest to Patagonia. Together, they cover nearly a quarter of the world’s coastlines and are among the planet’s most productive ecosystems. Giant kelp can grow up to two feet per day and sequester vast amounts of carbon, while protecting coastal communities from erosion and storms.

Kelp forests are among the most productive ecosystems on Earth, and some research suggests their carbon uptake rivals that of the Amazon rainforest per unit area. Absorbing up to two metric tons of carbon per hectare each year, they help buffer coastal waters from acidification. Giant kelps shelter and feed thousands of species, from fish and invertebrates to sea otters and seals, forming the foundation of rich marine food webs. Around the world, coastal and Indigenous communities depend on kelp for food, income and cultural traditions. Without these underwater forests, we would lose vital carbon sinks, biodiversity hotspots and sources of coastal protection and livelihood that sustain both ocean and human life.

But in California, a marine heatwave known as The Blob from 2014 to 2016 devastated these ecosystems. It formed when a persistent high-pressure system settled over the northeast Pacific, calming winds and reducing ocean mixing so that surface waters trapped and retained heat. With less upwelling of cold water and more direct sunlight, the region’s temperatures soared far above normal. As the planet warms, these marine heatwaves are expected to become more frequent, intense, and long-lasting due to rising baseline ocean temperatures and shifting atmospheric patterns. In Southern California, more than half of giant kelp forests vanished; in Central and Northern California, bull kelp declined by over 90% in some regions.

And yet, much resilience remains. In pockets where sea otters and sunflower sea stars have returned, kelp has rebounded. Scientists, divers and coastal communities are restoring kelp through creative collaborations: reseeding spores, managing urchins and reimagining fisheries that sustain both people and planet.

At a time when environmental amnesia creeps in – and when so much of modern life is lived through screens and filters – I find myself yearning to slow down. To be weathered and wise from years spent listening, documenting and immersing. To have salt crusted into my eyelashes, ink stained into the creases of my fingers and to somehow make a difference through it all. This three-part series for Parley’s Forests of the Sea project is an invitation to explore and join the movement. To return to the wildness still alive beneath the waves, to dive deeper into its wonders – and to help protect it.

Avery is a freediver, surfer and environmental science journalist based on a farm along the central coast of California. She writes and photographs most frequently for National Geographic and Scientific American, as well as Smithsonian Magazine, Popular Science Magazine, Grist, Atmos and others. In the second part of this series, she’ll dive back beneath the surface to explore how kelp forests can be both subject and collaborator, and how that empathy can move us toward climate action.