The all-female team tracking eagle rays in Mexico

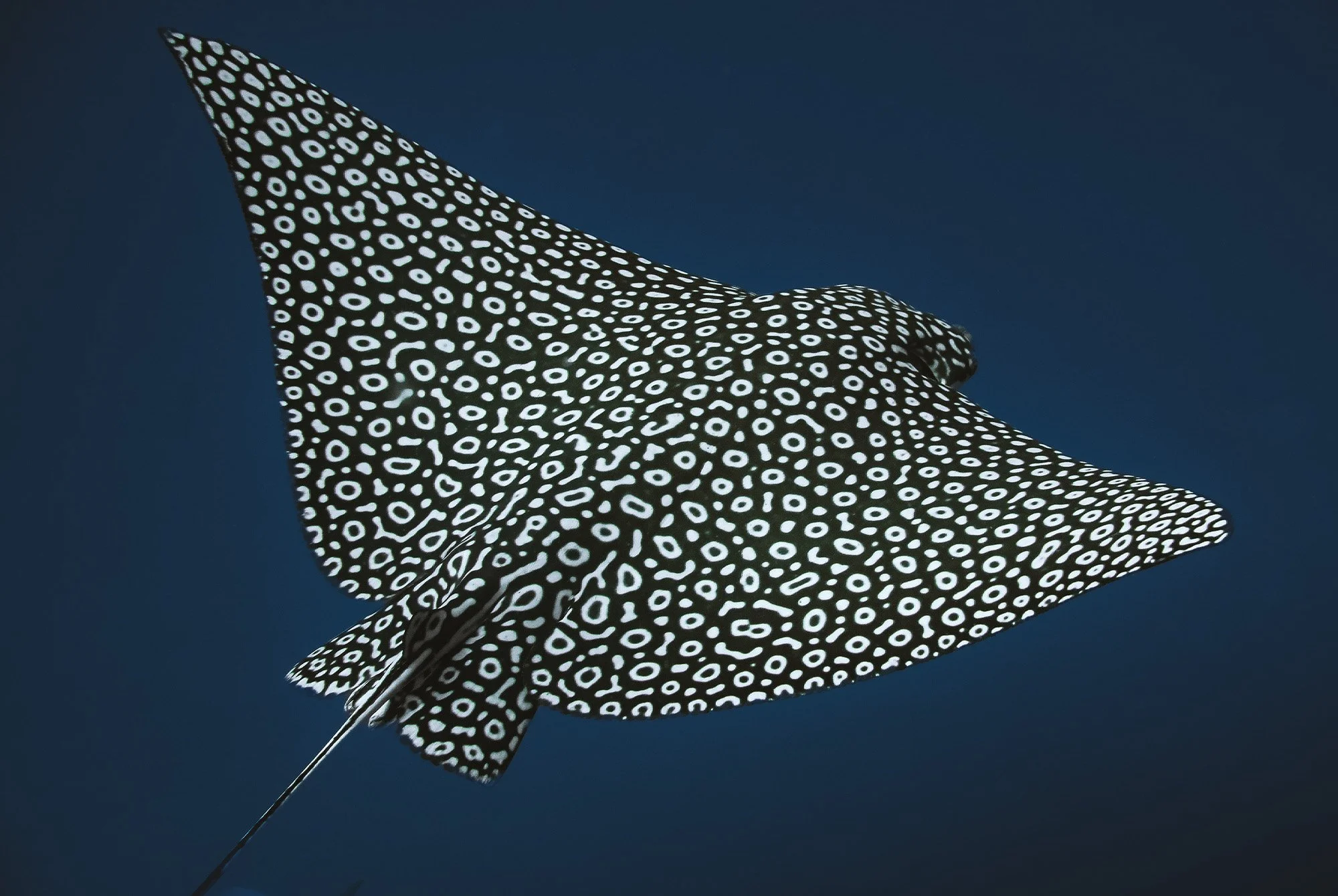

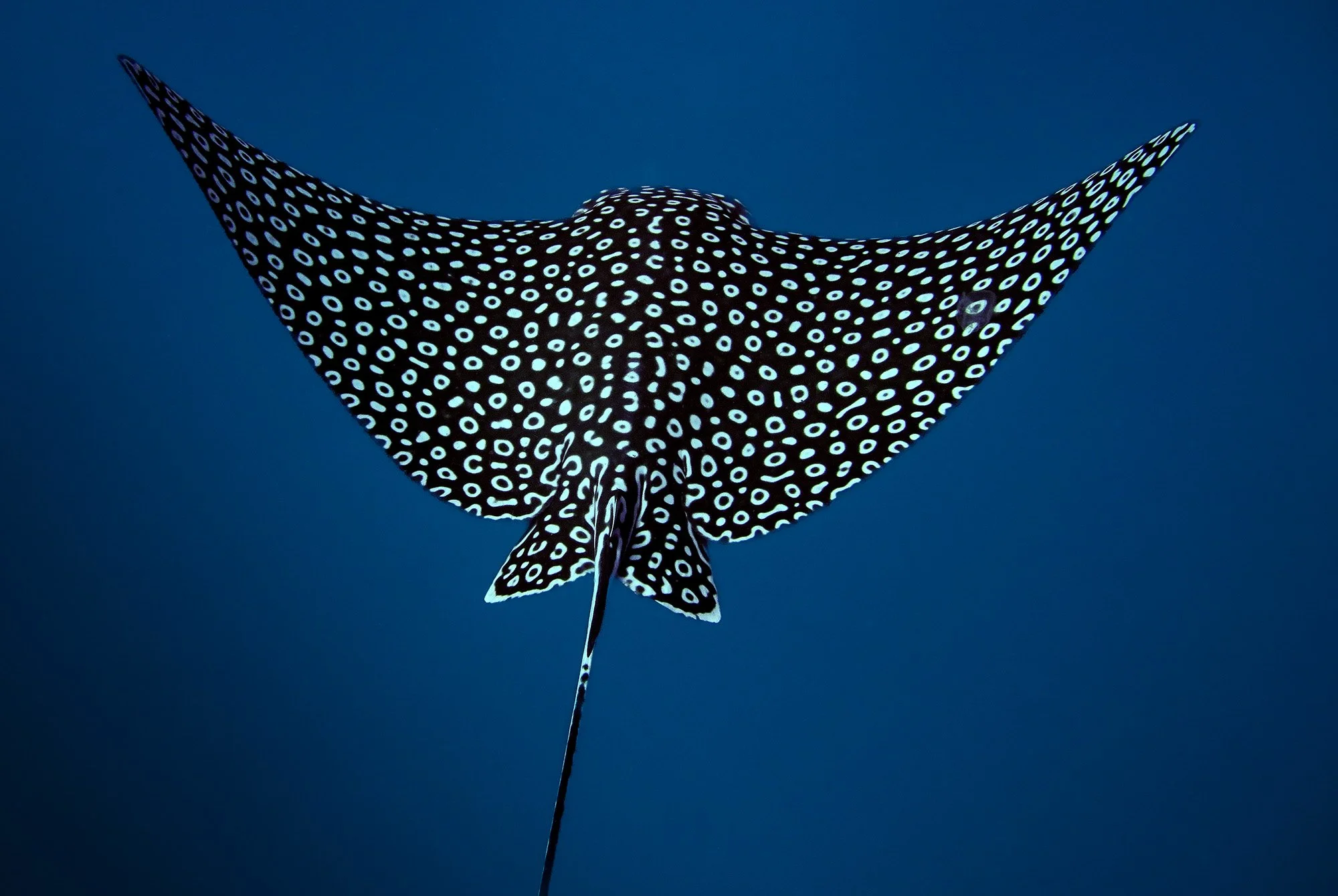

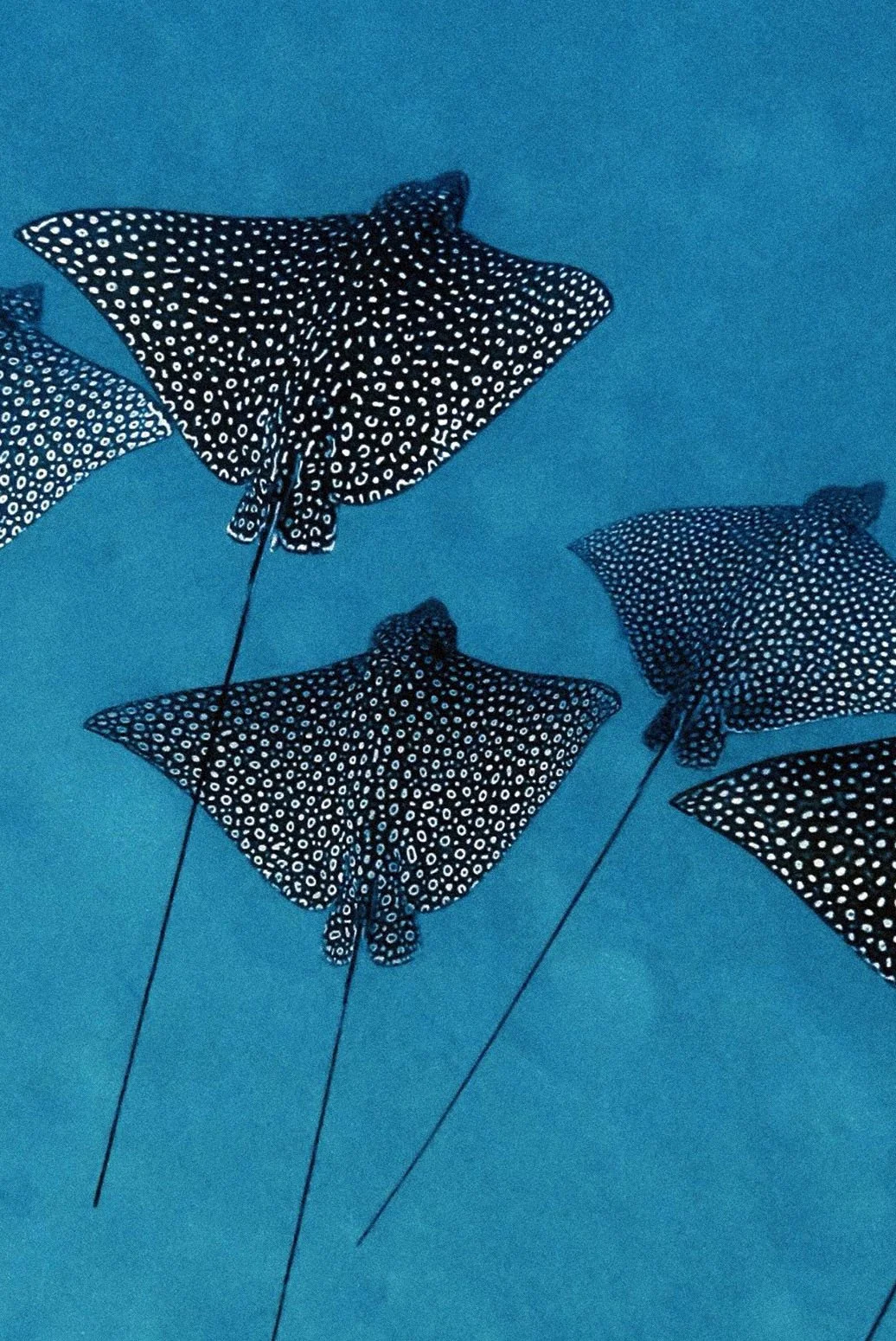

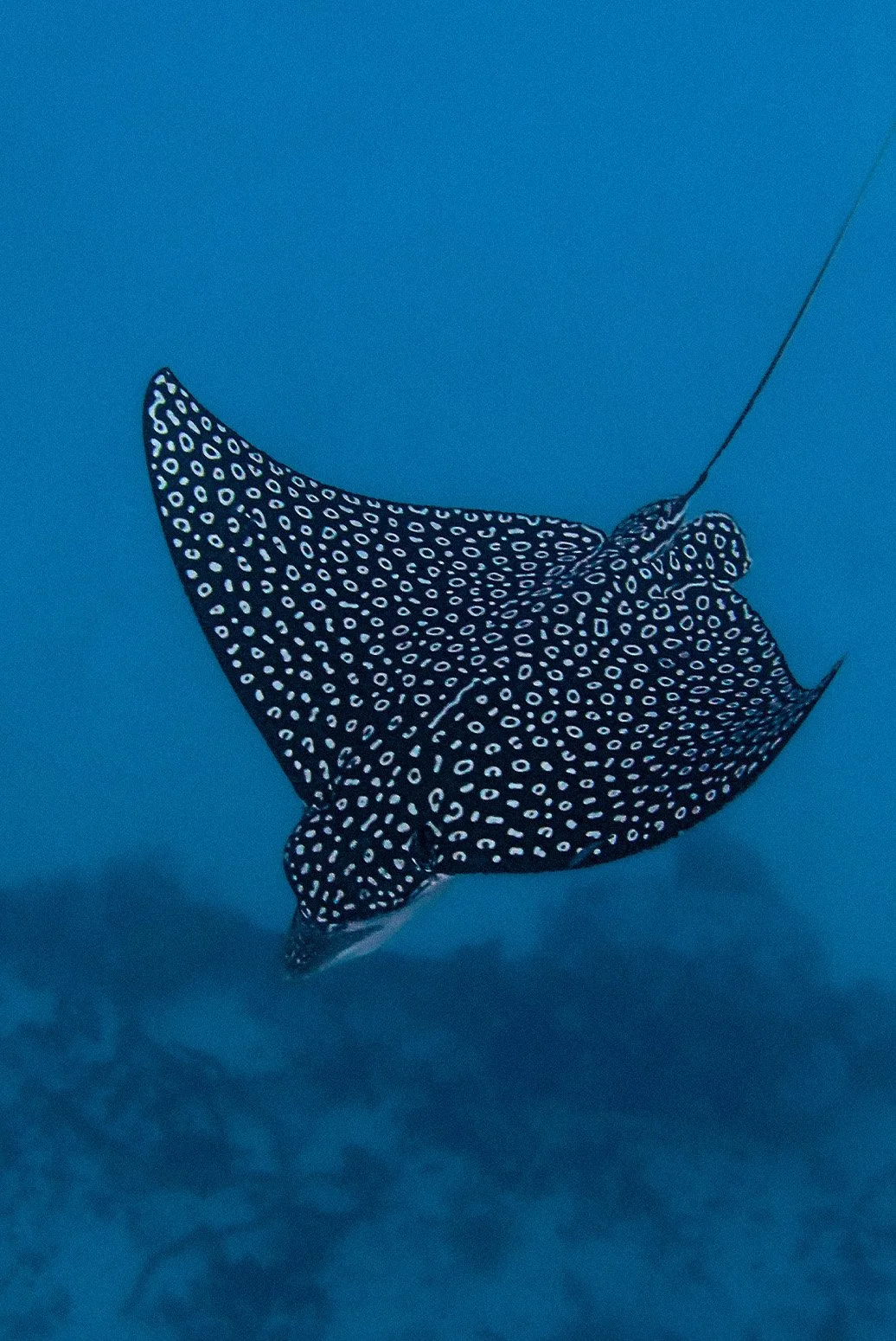

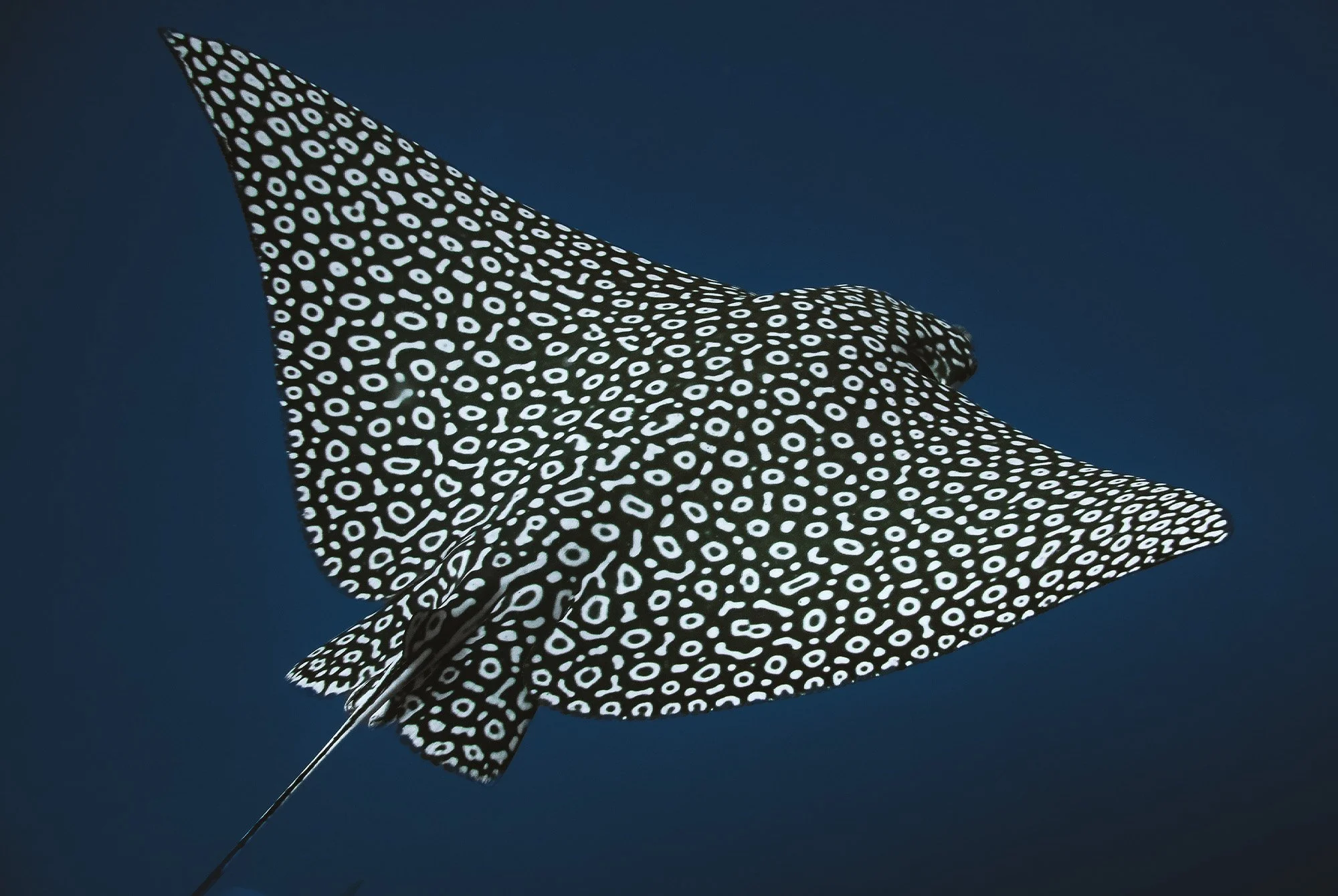

With their distinctive pop-art patterning – a unique signature made up of dots, rings and squiggles – spotted eagle rays are among among the most beautiful creatures in our oceans. to learn more, we caught up with the leaders of a Unique project studying these rays in the Mexican CaribbeaN

Beyond her work with Parley Mexico, Ximena Arvizu runs a unique initiative studying spotted eagle rays in the Mexican Caribbean. Blending cutting-edge science with the power of citizen participation, her Eagle Ray Project is revealing how photography, technology and community can transform our understanding and help protect one of the ocean’s most beautiful species. With the initiative now celebrating ten years of research, we caught up with Ximena and her colleague Florencia Cerutti to find out more. All images shown here are part of the project, so resolution can vary.

First of all, could you introduce yourselves and tell us what you do?

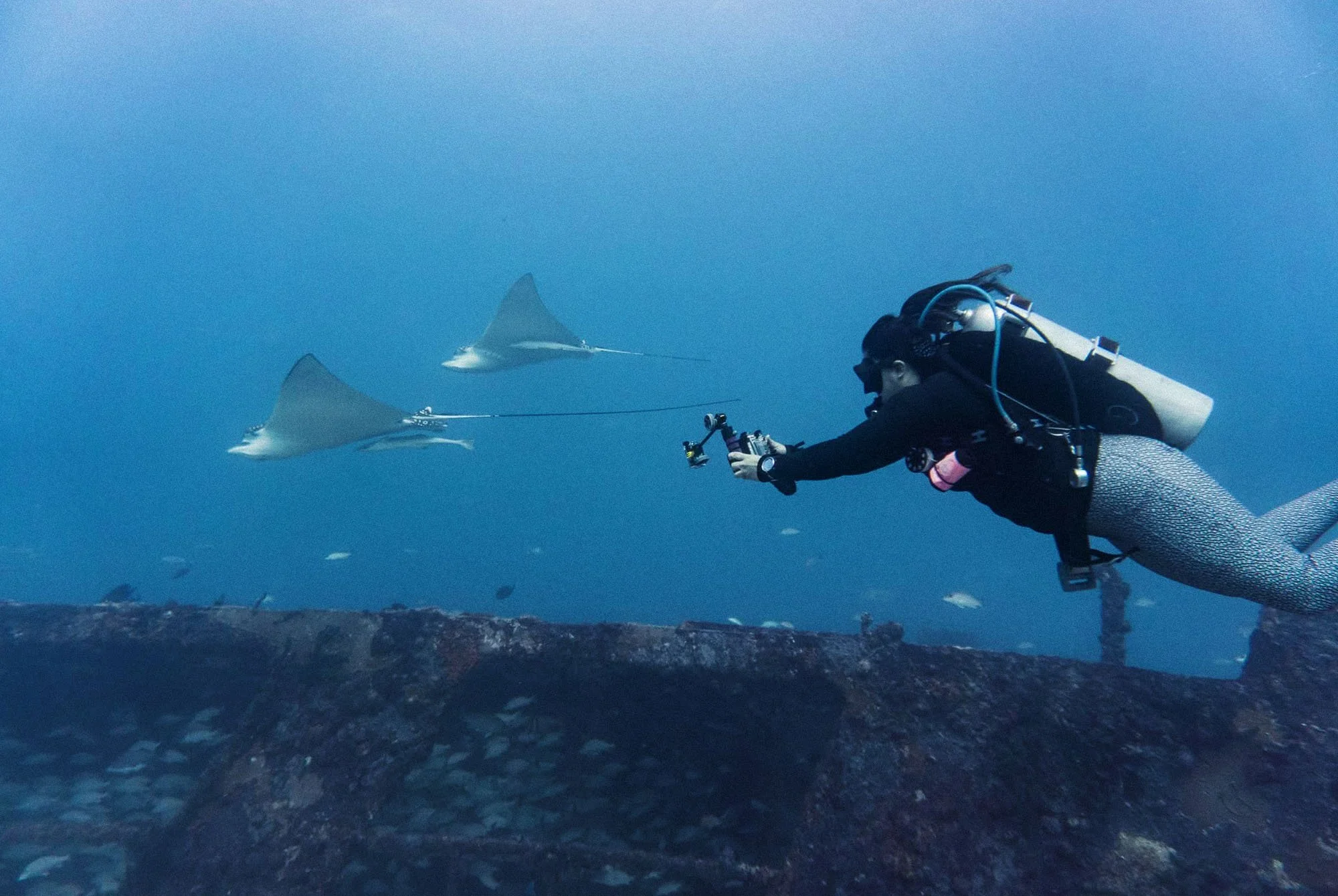

Ximena: Hi! I’m Ximena. I hold a Master’s degree in Protected Natural Areas Management and I’m the coastal cleanups coordinator for Parley Mexico. In my free time, I mainly dedicate myself to scuba diving and underwater photography, and I also coordinate shark and ray research and conservation projects in the Mexican Caribbean – especially the Eagle Ray Project.

Florencia: I’m Florencia Cerutti, a marine biologist specializing in sharks and rays. I began my career in La Paz, Mexico working with fisheries landings, and I’ve worked in various parts of the world including the Mexican Pacific and Caribbean, Australia, Indonesia, the Galápagos and Europe. During my PhD in Australia, I specialized in acoustic telemetry of tropical rays to understand their movements, habitat use and nursery areas.

What is the Eagle Ray Project?

Ximena: The Eagle Ray Project is a research and conservation initiative combined with citizen science that has been studying and raising awareness about spotted eagle rays in the Mexican Caribbean since 2015. Each ray has a unique spot pattern – like a fingerprint – and by using these images we can identify individuals without capturing them; this method is called photo-identification.

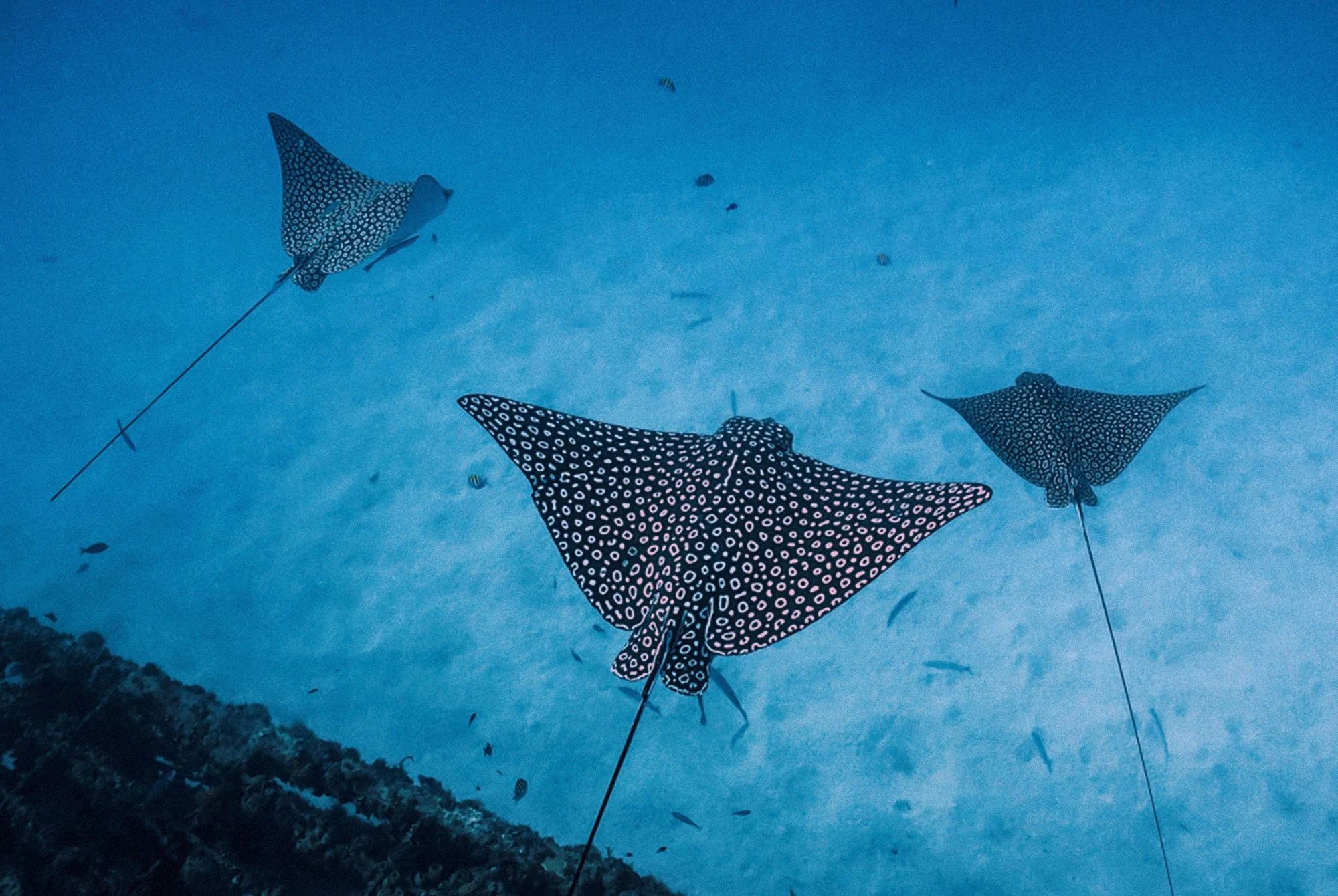

Since the beginning of the project, we’ve worked with the diving community and tourists, who contribute their photos. With this information, we maintain a photo library that allows us to estimate how many rays there are in the Mexican Caribbean and where they aggregate, detect whether they return to the same places and identify critical areas like nursery and aggregation sites to inform conservation actions and educate the local community.

Florencia: We currently have 410 identified individuals. Our study area covers the entire Mexican Caribbean, from Holbox to Xcalak (near the border with Belize). We currently work with 10 citizen scientists who regularly provide sightings and photos, as well as a network of collaborators and dive shops that help the project continue to grow. We also support other organizations in starting their own photo-ID catalogs and projects in other regions of the Caribbean.

How did it all begin?

Ximena: It all started very organically. Around 2013, a friend was invited by Kim Bassos from Mote Marine to learn about spotted eagle rays in Florida. Kim and Krystan at Mote have been studying this species in Sarasota for over 15 years. My friend knew how fascinated I was by this species and invited me to join her on the adventure.

At the same time, many divers – including us – had observed aggregations of rays around shipwrecks, but there was very little information at the time about the species and the reasons behind these aggregations. We decided to start a project to learn more about them, with support from Kim’s team. Neither of us had much experience with elasmobranchs (sharks and rays) or with developing research projects, so we sought help from experts. Coincidentally, Dr. Mauricio Hoyos was in the Caribbean studying bull sharks and put us in touch with Dr. Florencia Cerutti, who was in the area after finishing her PhD.

She joined without hesitation and developed the scientific foundations for a research project using photo-identification and citizen science. From that day on, Florencia became our scientific pillar, mentor and friend. Today, Dr. Cerutti and I continue to lead the project, which this year completes 10 monitoring seasons (December–March), and we continue to collaborate closely with the Mote Marine Lab team.

What have you learned in those ten years?

Ximena: Photo-identification combined with citizen science can be an incredibly powerful tool. Thanks to images contributed by divers, we created a photo library to identify unique individual eagle rays based on their spot patterns. This allows us to document individuals that return to the Caribbean (recaptures) and detect site fidelity – meaning there are places they clearly prefer, such as the shipwrecks in Cancún and Puerto Morelos and Ojo de Agua in Puerto Morelos. This has allowed us to begin identifying habitat-use patterns and some local movements without the need for capture.

I’ve also learned that conservation and science are greatly strengthened by community support. Collaboration with divers, snorkelers, and swimmers dramatically increases the capacity and reach of the study. The project has generated a lot of affection among divers; many feel like part of the team and regularly send us photos and information. Some collaborators have supported us for over a decade: for example, Flo Vergeer, a Canadian snorkeler who visits Puerto Morelos every year and faithfully sends us her photographs. This long-term commitment from the community provides continuity, allows us to detect inter-annual changes, and fosters local conservation, because people protect what they know and love.

What role does technology play in the project?

Ximena: Technology is key to our work. Underwater photography has evolved tremendously and allows us to use photo-identification as a non-invasive tool to identify and track individuals without capturing them. Our future goal is to incorporate acoustic and satellite telemetry to understand large-scale movements and connectivity.

This year we began using underwater laser photogrammetry to accurately measure the size of rays within aggregations and investigate whether they are adults or juveniles. Additionally, through our megafauna project funded by CONANP, we started using drones and underwater cameras to monitor the presence and distribution of spotted eagle rays within the Cancún–Isla Mujeres National Park. Today, with the widespread use of action cameras, it’s much easier for the community to capture videos and photos and share them with us; when used properly, this technology is a powerful ally for conservation.

Florencia: Currently, the project is also expanding through Master’s students and collaborations with Dr. Nicole Esteban from Swansea University, Dr. Gonzalo Araujo, director of MARECO, and the artificial intelligence (AI) platform developed by WildMe to apply AI to our photo-identification process. The model is being trained to recognize individual spotted eagle ray patterns, but this requires extensive metadata: angles, lighting, dates, locations and image quality.

“we still don’t know their large-scale migratory routes, habitat use, critical areas for species survival or long-term reproductive biology. All of this information is essential to assess vulnerability and properly conserve the species.”

Ximena Arvizu

What do we still not know about these beautiful creatures?

Ximena: Spotted eagle rays are migratory and represent an important economic resource in the region, both as a tourist attraction and for local fisheries. However, we still don’t know their large-scale migratory routes, habitat use, critical areas for species survival or long-term reproductive biology (such as juvenile survival rates, age at maturity, and reproductive frequency). All of this information is essential to assess vulnerability and properly conserve or manage the species.

Florencia: The taxonomy of spotted eagle rays also remains a major question. What was once considered a single species is actually a species complex, and more genetic studies are needed to clarify this further. At present, it appears that the species Aetobatus narinari occurs throughout the Atlantic in both Africa and the Americas, but this may change as more data become available.

What are your favorite facts about spotted eagle rays?

Ximena: Wow, such a hard question because I love everything about them! One fascinating fact is parthenogenesis: a few years ago, a spotted eagle ray in the Sydney Aquarium in Australia, while housed alone, gave birth to a pup genetically identical to its mother: a remarkable example of asexual reproduction, essentially a mini-clone. Additionally, spotted eagle rays are viviparous: the pups are born alive and already highly developed, around 40 cm long, with that characteristic snout and an irresistibly cute face.