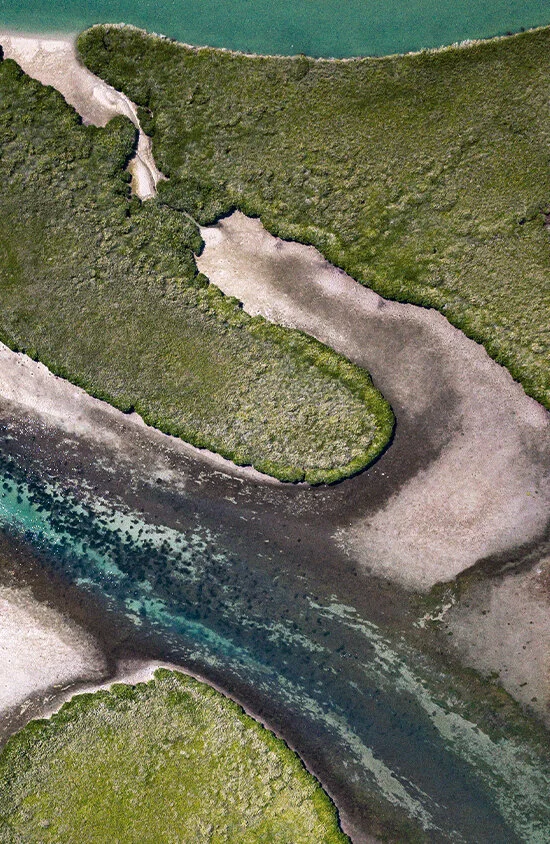

Mangroves: Oases of Complexity

In honor of World Wetlands Day, science writer and storyteller Ben Fiscella Meissner explores the many and mysterious intricacies, adaptations and advantages of coastal mangrove forests.

In our present era of climate change, civilization’s most threatened regions are coastlines. From sinking metropolises like Jakarta to the eroding coastlines of California and Louisiana to small island nations like the Maldives that have no ‘inland’ – many face the reality of being swallowed by the sea. Regardless of the land mass, humanity has always gravitated to the edge. Despite the massive space of interiors, about 40% of the world’s population lives within 100 km of a coast — be it access to the rich productivity of shallow coastal waters, the magnetism of commerce in ports, or the simple but profound, spiritual experience of resting one’s eyes on a water-filled horizon. The coast has long been regarded as this area of desire. But today, that desire is tinged with apprehension.

As rising seas reshape coastal paradise as we know it with utter indifference, it becomes apparent that our planet does not need us to change; we need us to change. The semi-fluid margin where land and ocean meet, may have once given us the illusion of permanence. At least long enough to decide where to erect idyllic beachfront infrastructure. But if we regard the coastline over time, we see a dynamic, undulating curtain disguised as a solid boundary. Life that thrives there, does not do so by adopting a false sense of permanence, but rather embraces an ephemeral philosophy of life.

This distinction in our perception of time and space reaches beyond the interests of real estate. If we understand our environment as perpetually changing, and currently at a pace quicker than what we had come to expect, then the development of our future cannot be based on a strategy of relocation or reinforcement. We must integrate adaptability as a core belief.

Contemplating the ancestral colonizers of our coastlines, thriving green metropolises that used to cover an estimated 75% of tropical coasts and inlets, could perhaps inform the necessary revisions to today’s developmental paradigm. The impulse to drain these “swamps” and declare a new beachfront might give us pause. Can we justify draining resilience to install fragility? This is about more than just the presence of a forested coastline that provides shelter and nourishment. It is about what we might learn by surrendering to nature’s complexity, and appreciating a coastal forest’s qualities of adaptation as worth incorporating into our own sense of residence.

Mangrove Propagule

“In order to thrive at the ocean's edge, mangroves exhibit vivipary, giving birth to live young, fully formed plants as opposed to dormant seeds, called propagules. Here a propagule of red mangrove has lodged itself in mud with the falling tide, its weighted bottom settling roots-first into the soil. These propagules can survive for weeks being carried for miles by tides and currents, allowing them to colonize new coastal margins.”

The impenetrable facade of a mangrove forest does not offer the same fluorescent welcome of a coral reef, like a tapestry of undulating colors and inviting textures spread out beneath you. And unlike a tropical or boreal forest, you won’t often find any well-worn footpath winding its way between trees. Mangrove forests are not designed to accommodate bipeds, or even most large mammals for that matter. The term mangrove refers to a collection of shrubs and trees, more than 70 species across various taxa, that can tolerate and thrive along the margin of land and sea. Though they cover just 0.1% of the continental Earth’s surface, their contribution to the ecological balance does not fit in a percentage point, nor can it speak to the carbon stored in their soils for thousands of years.

These coastal forests have been shaped over the course of their evolution to withstand and even thrive in our modern-day notion of apocalyptic conditions, occurring on a daily basis. At low tide, the exposed, above-ground root systems of Rhizophora mangle or red mangrove, can sit bone-dry on the tidal plain. The red mangrove is distributed globally across the tropics and subtropics, where it colonizes exposed coastal edges and creates a vision of chaos and a hyperproductive ecosystem. With the rising tide, these root systems become saltwater aquariums, vibrant nurseries for juvenile fish species to shelter in aquatic labyrinths where their size and agility are advantageous. Rich organic material that falls from the canopy above, along with terrestrial runoff provide an abundance of food, while the ample surface area of the roots provides ideal habitat for filter-feeding molluscs.

Instead of simply enduring the diurnal extremes of their dynamic environment, mangroves like Rhizophora have adapted to these fluctuations as a source of competitive advantage. At low tide, their stilted roots allow the plants to breathe through special pores called lenticels, a method of coping with compacted, waterlogged soil that would typically asphyxiate a plant. When water surges out or in with the tides, the architecture of roots provides enough support to withstand this sudden river of force. Larger core trunks supported by a clutter of stilted legs called prop roots maintain the forest canopy above the high water line, while collections of finer subterranean roots aid in nutrient uptake in the poor soil environment.

“Perhaps the most defining feature of mangroves is their ability to accept salt water as a constant.”

Perhaps the most defining feature of mangroves is their ability to accept salt water as a constant. This tolerance allows them to outcompete other plants and colonize the coast to form dense forests. Their adaptations vary by species, but mangroves can exclude salt, filtering water into the plant at the root level or excrete salt, expelling the mineral as a concentrated waste product through glands in their leaves. When the cellular level mechanisms for carrying salt out of the tree eventually wear out, the leaf litter provides rich organic matter to be fed upon in the shallow water meadows below. From here matter settles into the sediment-rich mud, incorporated into a layered process of decomposition that we may also appreciate as carbon sequestration.

Surviving in the relentless, salted, earthen edge of land masses, mangrove forests are perpetually growing, fortifying, filtering, and building. Man-made foundations on sand are as futile as sand castles, with far greater loss of resources. But mangroves maintain the coast at no cost, their subterranean roots holding sediment together, providing more substance to trap the soil.

Many characteristics of mangroves are difficult to study with precision, because so many aspects vary. The forest is such a dynamic and fluid place, that performing uniform measurements can be impossible. What is widely accepted is that when storm surges encounter the tangled wall of a mangrove forest, the energy is greatly dissipated. In hurricane-prone regions like the Caribbean, people bring their boats up the winding canals of mangrove forests to secure vessels before storm events, a telling sign of their natural defenses.

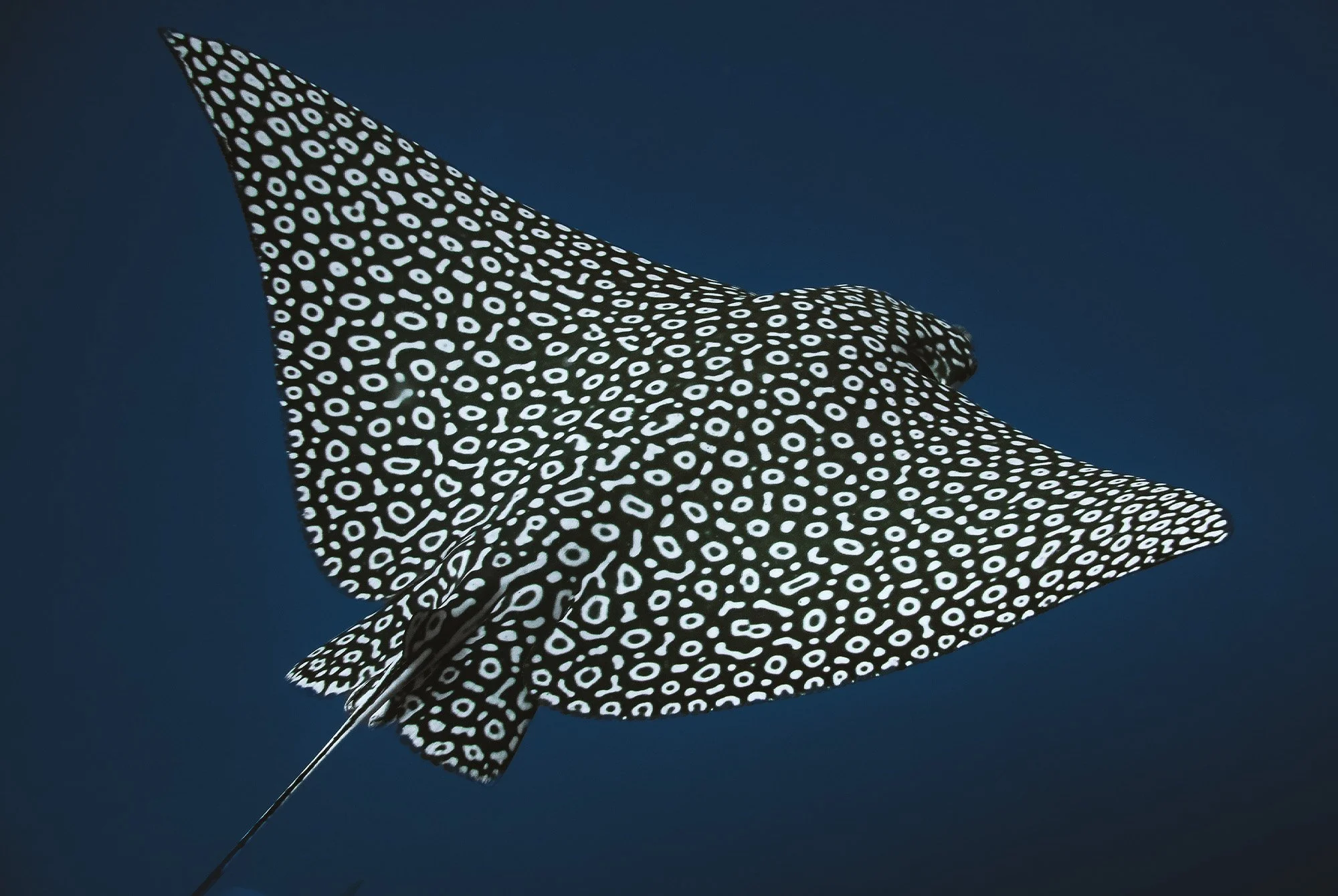

The importance of coastal mangroves as nurseries for fish populations cannot be overstated. The life cycle of many marine organisms uses a variety of habitats over the course of their life stages, and earlier stages require adequate refuge, food, and shelter from physical disturbances. Many larger species of fish, like snapper and grouper, use mangroves in juvenile stages before transitioning to more open habitats like coral reefs. The protection of mangroves should not be considered in a vacuum; they are links within a greater complex ecosystem sewn together by myriad relationships between elements and organisms. These forests are places of origination and fertility, a boon to everything when left intact.

Despite the scientific community’s dedicated pursuit of knowledge, these are but glimmers of understanding in a system that is not readily quantified, categorized and valued within our traditional measures of worth. It is difficult to pronounce sweeping claims of dollar amount values for a hectare of mangroves in Florida, India, and Mexico. Even the complex biochemical reaction of a leaf falling from a tree, to interact with bacteria, saltwater, microorganisms and fish is not readily understood, because any instance in which that leaf falls could be quite different from the next. But where measured certainty may fail, I think we can choose to regard the mangrove’s essence of adaptive persistence as an invaluable truth.

When we regard our knowledge of ecosystems in the present day, it is suffice to say that we know enough, to reveal our anthropocentric systems of development and commercial industry as antiquated and rigid to a fault. Our societies rely on natural resources, yet our chains of production fail to grasp the complexity of the ecosystems in which they function. As trends like biomimicry and nature-inspired processes grow, thrilling new inventions that harness just one characteristic of a plant or animal can miss the forest for the trees. Beyond any one sophisticated adaptation, like the use of ionized potassium molecules to exclude salt from water through a membrane, what if the concepts of ecosystem resilience and resistance were to become core values in all our routines and processes? The issues of our developing civilization will only grow more complex, but we can harness natural complexity without claiming to fully comprehend or own it.

Words and images by Ben Fiscella Meissner